(Press-News.org) People with end-stage renal disease often undergo hemodialysis, a life-sustaining blood-filtering treatment. To make the process as fast and efficient as possible, many people have "hemodialysis grafts" surgically implanted. These grafts are like bypasses, connecting a vein to a major artery, making it easier to access blood and ensuring the same blood doesn't get filtered twice.

But the grafts have a notorious problem: Clots tend to form where the graft is attached to the vein. For the person undergoing dialysis, this means not only a break from treatment, but also surgery to remove the graft and then surgery to implant another.

A multidisciplinary team from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and the university's McKelvey School of Engineering have devised a new way to design grafts that decreases the risk of clotting, ultimately relieving people of the pain, inconvenience and disruption of this critical treatment.

The research was published June 10 in the journal Scientific Reports.

In the United States, more than 500,000 people have end-stage renal disease.

"This has been a persistent problem for my patients, and we knew there had to be a better way," said Mohamed Zayed, MD, PhD, associate professor of surgery and of radiology in the section of vascular surgery and senior author of the study. "There is only so much blood thinner a patient can tolerate to prevent graft clotting, so we turned from pharmaceutical solutions to mechanobiology."

The field of mechanobiology considers all of the physical properties of a biological system, not simply the chemistry. How do the mechanical forces at play -- for example, pressure, elasticity, tension -- shape the formation of blood clots?

To figure it out, the researchers worked under the domain of the Center for Innovation in Neuroscience and Technology (CINT), a cross-disciplinary group working to remove classic barriers between engineering and medicine to allow a more fluid exchange of ideas and insights.

While a master's student at McKelvey, lead author Dillon Williams, now a doctoral student at the University of Minnesota, wrote his thesis on the redesign of dialysis grafts. "Dillon's key insight was that features of the surgery that the surgeon typically does not control can be tailored to reduce the chances that cells in the blood receive the mechanobiological cues that lead them to form clots," said Guy Genin, the Faught Professor of Mechanical Engineering at Washington University and joint senior author on the paper.

The surgeon doesn't have to simply build a bypass, but they can also act as a kind of civil engineer, paying attention to a specific design element in order to reduce the likelihood of a buildup of blood cells.

The team's research revealed that the crucial design element was the angle at which the graft and the vein were connected. It could be tailored so as to reduce both high and low rates of shear strain in the blood, a force that warps blood vessel walls in a specific way.

"These can be nearly eliminated by judicious choice of the attachment angle," Zayed said. "Although it is not always possible to reach the optimal range of attachment angles that Dillon discovered, the results tell us how to design prosthetic grafts that stand to reduce thrombosis [clot formation] substantially."

The work has been submitted as a non-provisional patent application -- Williams' second as a McKelvey student -- and the team hopes to bring it to the clinic soon. "CINT has a strong track record of bringing new technologies all the way to the clinic," said Eric Leuthardt, MD, professor of neurosurgery and director of CINT, and an author on the study. "Washington University is a place where we can bring together the right ideas and the right people, including outstanding McKelvey students like Dillon."

INFORMATION:

Funding

Washington University in St. Louis Skandalaris Center

Society for Vascular Surgery Foundation

American Surgical Association Foundation

National Institutes of Health National Heart and Lung and Blood Institute (No. R41HL150963)

Center for Innovation in Neuroscience and Technology at Washington University in St. Louis

National Science Foundation Science and Technology Center for Engineering MechanoBiology (No. CMMI 1548571)

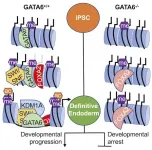

Scientists know that developing cells in a healthy embryo will transform into a variety of cell types that will make up the different organ systems in the human body, a process known as cell differentiation. But they don't know how the cells do it.

A Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) study in Cell Reports led by Stephen Duncan, D.Phil., examines how an endodermal cell - a type of developing cell - becomes a liver cell and not some other type of cell. Duncan and his team found that the development of naive cells into differentiated liver cells ...

Researchers have developed a new approach to gene therapy that leans on the common pain reliever acetaminophen to force a variety of genetic diseases into remission.

A paper published in Science Translational Medicine describes how the novel technique successfully treated the blood-clotting disorder hemophilia and the debilitating metabolic disease known as phenylketonuria, or PKU, in mice.

The approach uses a benign lentivirus to both correct disease-causing mutations and to insert a new gene that makes liver cells immune to the potentially toxic effects of acetaminophen. The latter ...

CINCINNATI--The disease is so rare and complex that its acronym is hard to pronounce. But for infants unlucky enough to be born with this lung disease, the outcome is usually fatal.

The disease is called alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of the pulmonary veins (ACDMPV). Research indicates the disease is linked to mutations in the FOXF1 gene. Worldwide, medical experts have documented about 200 cases, but an unknown number of infants may have died without the condition ever being diagnosed, according to the National Organization for Rare Disorders.

The disease is caused by genetic variations that prevent proper blood vessel formation in the lungs. Within ...

Los Alamos, N.M., June 10, 2021 - For the first time, the boundary of the heliosphere has been mapped, giving scientists a better understanding of how solar and interstellar winds interact.

Video link: https://youtu.be/w__vzNXSFoI

"Physics models have theorized this boundary for years," said Dan Reisenfeld, a scientist at Los Alamos National Laboratory and lead author on the paper, which was published in the Astrophysical Journal today. "But this is the first time we've actually been able to measure it and make a three-dimensional map of it."

The heliosphere is a bubble created by the solar wind, a stream ...

GAINESVILLE, Fla. --- An international research team has described a new species of Oculudentavis, providing further evidence that the animal first identified as a hummingbird-sized dinosaur was actually a lizard.

The new species, named Oculudentavis naga in honor of the Naga people of Myanmar and India, is represented by a partial skeleton that includes a complete skull, exquisitely preserved in amber with visible scales and soft tissue. The specimen is in the same genus as Oculudentavis khaungraae, whose original description as the smallest known bird was retracted last year. The two fossils were found in the same area and are about 99 million years ...

What The Study Did: The results suggest assisted living residents experienced increased mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic consistent with increases observed among nursing home residents.

Authors: Kali S. Thomas, Ph.D., of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13411)

Editor's Note: The article includes funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional ...

What The Study Did: Researchers examined the association between the amount of ultra-processed food consumed by children and their weight in early adulthood.

Authors: Kiara Chang, Ph.D., of Imperial College London, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.1573)

Editor's Note: The article includes funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: ...

What The Study Did: Differences by sex and race/ethnicity in suicidal thoughts and nonfatal suicide attempts among U.S. adolescents over the last three decades were assessed in this survey study.

Authors: Yunyu Xiao, Ph.D., of Indiana University-Purdue University in Indianapolis, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13513)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflicts of interest disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including ...

Diseases that affect tubular structures in the body, such as the gastrointestinal (GI) system, vasculature and airway, present a unique challenge for delivering local treatments. Vertically oriented organs, such as the esophagus, and labyrinthine structures, such as the intestine, are difficult to coat with therapeutics, and in many cases, patients are instead prescribed systemic drugs that can have immunosuppressive effects. To improve drug delivery for diseases that affect tubular organs, like eosinophilic esophagitis and inflammatory bowel disease, ...

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- Inspired by kirigami, the Japanese art of folding and cutting paper to create three-dimensional structures, MIT engineers and their collaborators have designed a new type of stent that could be used to deliver drugs to the gastrointestinal tract, respiratory tract, or other tubular organs in the body.

The stents are coated in a smooth layer of plastic etched with small "needles" that pop up when the tube is stretched, allowing the needles to penetrate tissue and deliver a payload of drug-containing microparticles. Those drugs are then released over an extended period of time after the stent is removed.

This kind of localized drug delivery could make it easier ...