(Press-News.org) CHAPEL HILL, NC - UNC School of Medicine scientists led a collaboration of researchers to demonstrate a potentially powerful new strategy for treating cystic fibrosis (CF) and potentially a wide range of other diseases. It involves small, nucleic acid molecules called oligonucleotides that can correct some of the gene defects that underlie CF but are not addressed by existing modulator therapies. The researchers used a new delivery method that overcomes traditional obstacles of getting oligonucleotides into lung cells.

As the scientists reported in the journal Nucleic Acids Research, they demonstrated the striking effectiveness of their approach in cells derived from a CF patient and in mice.

"With our oligonucleotide delivery platform, we were able to restore the activity of the protein that does not work normally in CF, and we saw a prolonged effect with just one modest dose, so we're really excited about the potential of this strategy," said study senior author Silvia Kreda, PhD, an associate professor in the UNC Department of Medicine and the UNC Department Biochemistry & Biophysics, and a member of the Marsico Lung Institute at the UNC School of Medicine.

Kreda and her lab collaborated on the study with a team headed by Rudolph Juliano, PhD, Boshamer Distinguished Professor Emeritus in the UNC Department of Pharmacology, and co-founder and Chief Scientific Officer of the biotech startup Initos Pharmaceuticals.

About 30,000 people in the United States have CF, an inherited disorder in which gene mutations cause the functional absence of an important protein called CFTR. Absent CFTR, the mucus lining the lungs and upper airways becomes dehydrated and highly susceptible to bacterial infections, which occur frequently and lead to progressive lung damage.

Treatments for CF now include CFTR modulator drugs, which effectively restore partial CFTR function in many cases. However, CFTR modulators cannot help roughly ten percent of CF patients, often because the underlying gene defect is of the type known as a splicing defect.

CF and splicing defects

Splicing is a process that occurs when genes are copied out - or transcribed - into temporary strands of RNA. A complex of enzymes and other molecules then chops up the RNA strand and re-assembles them, typically after deleting certain unwanted segments. Splicing occurs for most human genes, and cells can re-assemble the RNA segments in different ways so different versions of a protein can be made from a single gene. However, defects in splicing can lead to many diseases - including CF when CFTR's gene transcript is mis-spliced.

In principle, properly designed oligonucleotides can correct some kinds of splicing defects. In recent years the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved two "splice switching oligonucleotide" therapies for inherited muscular diseases.

In practice, though, getting oligonucleotides into cells, and to the locations within cells where they can correct RNA splicing defects, has been extremely challenging for some organs.

"It has been especially difficult to get significant concentrations of oligonucleotides into the lungs to target pulmonary diseases," Kreda said.

Therapeutic oligonucleotides, when injected into the blood, have to run a long gauntlet of biological systems that are designed to keep the body safe from viruses and other unwanted molecules. Even when oligonucleotides get into cells, the most usually are trapped within vesicles called endosomes, and are sent back outside the cell or degraded by enzymes before they can ever do their work.

A new delivery strategy

The strategy developed by Kreda, Juliano, and their colleagues overcomes these obstacles by adding two new features to splice switching oligonucleotides: Firstly, the oligonucleotides are connected to short, protein-like molecules called peptides that are designed to help them to distribute in the body and get into cells. Secondly, there is a separate treatment with small molecules called OECs, developed by Juliano and Initos, which help the therapeutic oligonucleotides escape their entrapment within endosomes.

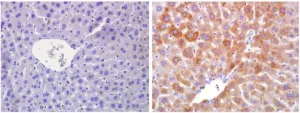

The researchers demonstrated this combined approach in cultured airway cells from a human CF patient with a common splicing-defect mutation.

"Adding it just once to these cells, at a relatively low concentration, essentially corrected CFTR to a normal level of functioning, with no evidence of toxicity to the cells," Kreda said.

The results were much better with than without OECs, and improved with OEC dose.

There is no mouse model for splicing-defect CF, but the researchers successfully tested their general approach using a different oligonucleotide in a mouse model of a splicing defect affecting a reporter gene. In these experiments, the researchers observed that the correction of the splicing defect in the mouse lungs lasted for at least three weeks after a single treatment - hinting that patients taking such therapies might need only sporadic dosing.

The researchers now plan further preclinical studies of their potential CF treatment in preparation for possible clinical trials.

INFORMATION:

Yan Dang, Catharina van Heusden, Veronica Nickerson, Felicity Chung, Yang Wang, Nancy Quinney, Martina Gentzsch, and Scott Randell were other contributors to this study from the Marsico Lung Institute; Ryszard Kole a co-author from the UNC Department of Pharmacology.

The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and the National Institutes of Health supported this work.

Stuttgart/Boulder - It is not the first time that spiders have served as biological models in the research field of soft robotics. The hydraulic actuation mechanisms they apply to move their limbs when weaving their web or hunting for prey give them powers many roboticists and engineers have drawn inspiration from.

A team of researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems in Germany and at the University of Boulder in Colorado in the US has now found a new way to exploit the principles of spiders' joints to drive articulated robots without any bulky components and connectors, which weigh down the robot and reduce portability and speed. Their slender and lightweight simple ...

Magnetic-spin interactions that allow spin-manipulation by electrical control allow potential applications in energy-efficient spintronic devices.

An antisymmetric exchange known as Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interactions (DMI) is vital to form various chiral spin textures, such as skyrmions, and permits their potential application in energy-efficient spintronic devices.

Published this week, a Chinese-Australia collaboration has for the first time illustrated that DMI can be induced in a layered material tantalum-sulfide (TaS2) by intercalating iron atoms, and can further be tuned by gate-induced proton intercalation.

REALIZING AND TUNING DMI IN VAN-DER-WAALS MATERIAL TaS2

Searching ...

WASHINGTON --Just a small number of cells found in tumors can enable and recruit other types of cells nearby, allowing the cancer to spread to other parts of the body, report END ...

It sounds like a plot from a Quentin Tarantino movie -- something sets off natural killers and sends them on a killing spree.

But instead of characters in a movie, these natural killers are part of the human immune system and their targets are breast cancer tumor cells. The triggers are fusion proteins developed by Clemson University researchers that link the two together.

"The idea is to use this bifunctional protein to bridge the natural killer cells and breast cancer tumor cells," said Yanzhang (Charlie) Wei, a professor in the College of Science's Department of Biological Sciences. "If the two cells are brought close enough together through this receptor ligand connection, the natural killer cells can release what I call killing machinery to have the tumor cells killed."

It's ...

A group of researchers from the University of Jyvaskyla and Stanford University were part of an expedition to French Guiana to study tropical frogs in the Amazon. Various amphibian species of this region use ephemeral pools of water as their nurseries, and display unique preferences for specific physical and chemical characteristics. Despite species-specific preferences, researchers were surprised to find tadpoles of the dyeing poison frog surviving in an incredible range of both chemical (pH 3-8) and vertical (0-20 m in height) deposition sites. This research was published in the journal Ecology and Evolution in June 2021.

Neotropical frogs are special because, unlike species in temperate regions, many tropical frogs ...

Postdoctoral Researcher Outi Keinänen from the University of Helsinki developed a method to radiolabel plastic particles in order to observe their biodistribution on the basis of radioactivity with the help of positron emission tomography (PET). As a radiochemist, Keinänen has in her previous radiopharmaceutical studies utilised PET imaging combined with computed tomography (CT), which produces a very accurate image of the anatomical location of the radioactivity signal.

In the recently completed study, radiolabelled plastic particles were fed to mice, and their elimination from the body was followed with PET-CT scans. This was the first time that ...

Research published today in the Journal of General Virology has identified missed cases of SARS-CoV-2 by retrospective testing of throat swabs.

Researchers at the University of Nottingham screened 1,660 routine diagnostic specimens which had been collected at a Nottingham hospital between 2 January and 11 March 2020 and tested for SARS-CoV-2 by PCR. At this stage of the pandemic, there was very little COVID-19 testing available in hospitals, and to qualify patients had to meet a strict criterion, including recent travel to certain countries in Asia or contact with a known positive case.

Three previously unidentified cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection were identified by the retrospective screening, including one from a 75-year-old ...

The phenomenon of quantum nonlocality defies our everyday intuition. It shows the strong correlations between several quantum particles some of which change their state instantaneously when the others are measured, regardless of the distance between them. While this phenomenon has been confirmed for slow moving particles, it has been debated whether nonlocality is preserved when particles move very fast at velocities close to the speed of light, and even more so when those velocities are quantum mechanically indefinite. Now, researchers from the University of Vienna, the Austrian Academy of Sciences and the Perimeter Institute report in the latest issue of Physical Review Letters that ...

Tokyo, Japan - Colloids--mixtures of particles made from one substance, dispersed in another substance--crop up in numerous areas of everyday life, including cosmetics, food and dyes, and form important systems within our bodies. Understanding the behavior of colloids therefore has wide-ranging implications, yet investigating the rotation of spherical particles has been challenging. Now, an international team including researchers from The University of Tokyo Institute of Industrial Science has created particles with an off-center core or "eye" that can be tracked ...

Getting energy and nutrients from the environment - that is, eating - is such an important function that it has been regulated through sophisticated mechanisms over hundreds of millions of years. Some of these mechanisms are only now beginning to be unravelled. A group at the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO) has found one of their key components - a switch that controls the ability of organisms to adapt to low cellular nutrient levels.

The protein involved is RagA, which is part of the mTOR molecular pathway, whose importance in metabolic activity regulation has been known for decades now. CNIO researchers have found that if RagA is continuously activated, cells do not know that there are no sufficient nutrients and so ...