(Press-News.org) New study challenges long-standing assumptions about disease severity in infants, and suggests that standard qPCR interpretations underestimate the true burden of other highly contagious diseases, such as COVID-19 and influenza.

Pertussis, also known as "whooping cough," remains a significant cause of death in infants and young children around the world and, despite global vaccination programs, many countries are experiencing a resurgence of this highly contagious disease.

A new study by Boston University School of Public Health and the University of Georgia's Odum School of Ecology presents evidence that could help explain this resurgence: asymptomatic individuals. Lots of them.

Published in the journal eLife, the study suggests that most adults and many children who contract pertussis display no symptoms at all--a reversal of what many experts have long believed about an infection that can cause months of violent coughing fits and "whooping" sounds.

The paper builds upon a 2015 study in which the researchers discovered a series of weakly positive pertussis infections after collecting nasal swab samples from 2,000 mother/infant pairs in Zambia every 2-3 weeks for several months, using quantitative PCR (qPCR) diagnosis. In a standard qPCR analysis, these low-intensity signals would be discounted as false-positive results. But the repeated clusters of mother/infant cases, which illustrated a natural arc of infection as the infection ran its course, suggested that these weak PCR signals provided important information about disease.

"The fact that we found concordance within the mother/infant pairs told us that, in all likelihood, even the weakly affected mothers are contagious at close range, and are probably infecting their babies," says Dr. Christopher Gill, co-lead author of the study and associate professor of global health at BUSPH. Asymptomatic spread is not a unique phenomenon with infectious diseases, he says, but as the world has seen with COVID-19, the ability to detect asymptomatic infections early and accurately through qPCR can provide vital information about the epidemiology and burden of diseases.

"This was a quest to understand weakly positive qPCR and then determine what proportion of pertussis transmissions are coming from asymptomatic people," Gill says.

To confirm that these weak signals were accurate and relevant, the researchers conducted a closer analysis for the eLife study, and discovered additional evidence supporting the likelihood of asymptomatic transmission. The cluster of weak signals aligned with stronger signals, indicating that they occurred during an outbreak; the clusters reflected the natural rise and fall of an epidemic; signals were strongly clustered within mother/infant pairs; and the stronger the qPCR signal, the more likely individuals were to experience symptoms.

Confident in their findings, the researchers then compared the symptomatic cases to the asymptomatic cases and discovered that about 70% of infected mothers displayed no symptoms, and about 25% of infected babies displayed no symptoms. And infants with only mild symptoms (cough or runny nose) comprised over 50% of infections.

"We expected this in mothers, since pertussis becomes less severe with age and repeat exposure," says co-lead author Dr. Christian Gunning, post-doctoral researcher at UGA's School of Ecology. "But mild and asymptomatic infection in infants was assumed to be quite rare. And what we see here is the opposite--severe pertussis in infants is the exception rather than the rule."

The findings underscore the need for a shift in the way qPCR tests are interpreted, Gill says.

"Using a 'line in the sand' approach to interpret results is too simplistic and leads us to discard true and useful information," he says. "If one were trying to map a flu season, it would make more sense to use the weakly positive PCR results as an early warning of impending flu outbreaks, rather than waiting for symptomatic patients with very strong PCR results to start showing up in the ER."

Gunning agrees, saying disease surveillance plays an important role in preventing and responding to disease outbreaks. "Our results differ from traditional approaches that medical doctors use to diagnose and treat patients," he says. "When we tested many people many times, we could 'peer under the hood' and see a lot of hidden infections in this population."

Gunning says that a similar approach could help monitor for outbreaks of COVID. "To control disease outbreaks, we need to know when and where the disease has spread. New strategies like wastewater monitoring could leverage weak qPCR signals to give us a better, fasteridea of who's at risk, and allow us to more quickly intervene. And if you only look at sick people, you're going to miss a lot."

INFORMATION:

At SPH, the study was co-authored by William MacLeod, research associate professor, Lawrence Mwananyanda, adjunct research assistant professor, Donald Thea, associate professor of global health, and Rachel Pieciak, research fellow. Additional co-authors are Geoffrey Kwenda of the University of Zambia, Zacharia Mupila of Right to Care, and Pejman Rohani, of UGA. Funding for the research was provided by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Diseases under award number R01AI133080.

About the Boston University School of Public Health

Founded in 1976, the Boston University School of Public Health is one of the top five ranked private schools of public health in the world. It offers master's- and doctoral-level education in public health. The faculty in six departments conduct policy-changing public health research around the world, with the mission of improving the health of populations--especially the disadvantaged, underserved, and vulnerable--locally and globally.

About the University of Georgia Odum School of Ecology

Through research, teaching and public service, the Odum School of Ecology at the University of Georgia is shaping the future of ecological inquiry and application to better understand our rapidly changing planet. It offers graduate and undergraduate degrees in ecology and conservation. Areas of particular focus include conservation ecology, ecosystem ecology and disease ecology. The world's first school committed solely to the study of ecology, its roots date back to the 1950s when namesake and founder Eugene P. Odum began his groundbreaking ecosystem ecology research at UGA.

Bottom Line: Genetic mutations indicative of DNA damage were associated with high red meat consumption and increased cancer-related mortality in patients with colorectal cancer.

Journal in Which the Study was Published: Cancer Discovery, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research

Author: Marios Giannakis, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and a physician at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

Background: "We have known for some time that consumption of processed meat and red meat is a risk factor for colorectal cancer," said Giannakis. The International Agency for Research on Cancer declared that processed meat was carcinogenic and that red meat was probably carcinogenic to humans in 2015.

Experiments ...

HOUSTON ? Preclinical research from The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center finds that although glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs) can be targeted by natural killer (NK) cells, they are able to evade immune attack by releasing the TFG-β signaling protein, which blocks NK cell activity. Deleting the TFG-β receptor in NK cells, however, rendered them resistant to this immune suppression and enabled their anti-tumor activity.

The findings, published today in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, suggest that engineering NK cells to resist immune suppression may be a feasible path ...

The energy density of traditional lithium-ion batteries is approaching a saturation point that cannot meet the demands of the future - for example in electric vehicles. Lithium metal batteries can provide double the energy per unit weight when compared to lithium-ion batteries. The biggest challenge, hindering its application, is the formation of lithium dendrites, small, needle-like structures, similar to stalagmites in a dripstone cave, over the lithium metal anode. These dendrites often continue to grow until they pierce the separator membrane, causing the battery to short-circuit and ultimately destroying ...

Nitrogen from agriculture, vehicle emissions and industry is endangering butterflies in Switzerland. The element is deposited in the soil via the air and has an impact on vegetation - to the detriment of the butterflies, as researchers at the University of Basel have discovered.

More than half of butterfly species in Switzerland are considered to be at risk or potentially at risk. Usually, the search for causes focuses on intensive agriculture, pesticide use and climate change. A research team led by Professor Valentin Amrhein from the University of Basel, however, has been investigating another factor - the depositing ...

Living beings are continuously exposed to harmful agents, both exogenous (ultraviolet radiation, polluting gases, etc.) and endogenous (secondary products of cellular metabolism) that can affect DNA integrity. That's why cells are endowed with a series of molecular mechanisms whose purpose is to identify and signpost possible damage to the genetic material for speedy repair. These mechanisms are precisely regulated because they are key to cell survival. In extreme situations of massive and irreparable damage, cells enter a phase of controlled dismantling called "programmed cell death". Among the events that take place during this process is the massive delivery to the cytoplasm of a mitochondrial protein called cytochrome C. Under homeostatic conditions, this protein plays a role in energy ...

The 2018 Nobel Prize in Physics was shared by researchers who pioneered a technique to create ultrashort, yet extremely high-energy laser pulses at the University of Rochester.

Now researchers at the University's Institute of Optics have produced those same high-powered pulses--known as chirped pulses--in a way that works even with relatively low-quality, inexpensive equipment. The new work could pave the way for:

Better high-capacity telecommunication systems

Improved astrophysical calibrations used to find exoplanets

Even more accurate atomic clocks

Precise devices for measuring chemical contaminants in the atmosphere

In a paper in Optica, the researchers describe the first demonstration ...

Peatlands are an important ecosystem that contribute to the regulation of the atmospheric carbon cycle. A multidisciplinary group of researchers, led by the University of Helsinki, investigated the climate response of a permafrost peatland located in Russia during the past 3,000 years. Unexpectedly, the group found that a cool climate period, which resulted in the formation of permafrost in northern peatlands, had a positive, or warming, effect on the climate.

The period studied, which began 3,000 years ago, is known as a climate period of cooling temperatures. The climate-related effect of permafrost formation brought about by the cooling was investigated particularly by analysing the ancient plant communities of the peatland, using similarly analysed peatland data from elsewhere in ...

An international survey by the University of Münster's Cluster of Excellence "Religion and Politics" provides the first empirical evidence of an identity-related political cleavage of European societies that has resulted in the emergence of two entrenched camps of substantial size. "We see two distinct groups with opposing positions, which we call 'Defenders' and 'Explorers'", says psychologist Mitja Back, spokesperson of the interdisciplinary research team that conducted the most comprehensive survey of identity conflicts in Europe to date. "Who belongs to our country, who threatens whom, who is disadvantaged? Across all such questions of identity, the initial analyses of the survey reveal a new line of conflict between the two groups, which have almost diametrically opposite ...

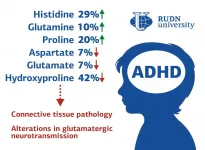

RUDN University doctors found alterations in serum amino acid profile in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The findings will help to understand the mechanism of the disorder and develop new treatment strategies. The study is published in the journal Biomedical Reports.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that manifests itself in childhood. Children with ADHD find it difficult to concentrate and manage their impulsivity. It is known that ADHD is also manifested at the neurochemical level -- for example, the work of dopamine and norepinephrine is disrupted. However, there is still no definitive data ...

The death of a mother is a traumatic event for immature offspring in species in which mothers provide prolonged maternal care, such as in long-lived mammals, including humans. Orphan mammals die earlier and have less offspring compared with non-orphans, but how these losses arise remains under debate. Clinical studies on humans and captive studies on animals show that infants whose mothers die when they are young are exposed to chronic stress throughout their lives. However, such chronic stress, which has deleterious consequences on health, can be reduced or even cancelled if human orphans are placed in foster families young enough. How stressed orphans are in the wild and whether ...