A detailed atlas of the developing brain

Harvard and Broad researchers combine single-cell genomic technologies to map the mouse cortex

2021-06-24

(Press-News.org) Researchers at Harvard University and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard have created a first detailed atlas of a critical region of the developing mouse brain, applying multiple advanced genomic technologies to the part of the cerebral cortex that is responsible for processing sensation from the body. By measuring how gene activity and regulation change over time, researchers now have a better understanding of how the cerebral cortex is built, as well as a brand new set of tools to explore how the cortex is affected in neurodevelopmental disease. The study is published in the journal Nature.

"We have had a long-standing interest in understanding the development of the mammalian cerebral cortex, as it is the seat of higher-order cognition and the part of the brain that has expanded and diversified the most during human evolution," said Paola Arlotta, the co-senior author of the study and the Golub Family Professor of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology at Harvard University. "In this study, we looked at the cortex with a very fine lens, practically profiling all of its cells, one by one, every day of development. We catalogued changes in gene expression and regulation at an unprecedented level of temporal resolution to build a first single-cell-resolution molecular map of this amazing tissue. The map allowed us to extract first mechanistic principles governing how the cortex is built, and begin to decode how genetic abnormalities affect such highy controlled process in the embryo."

"In the developing brain, we have to consider three things: the types of cells that are present, where those cells are located, and at what stage they are in development. In addition, by identifying the drivers that direct this process in normal development, we can better understand what may go wrong in disease," said co-senior author Aviv Regev, who was a core institute member at the Broad Institute when the study began and is currently Head of Genentech Research and Early Development.

The researchers focused on the somatosensory cortex, which may serve as a model for other regions of the cerebral cortex because it contains cells representing all of its major classes. For every day of cortex development, the researchers analyzed the brain using multiple technologies at the single-cell level. They used RNA-seq to measure which genes are expressed, as well as spatial transcriptomics to measure where genes are expressed in the tissue. They also used ATAC-seq to measure which parts of the genome were accessible for regulation.

"These technologies allowed us to look at different modes of gene expression and how genes are regulating each other. By combining these three modalities, we have a stronger sense of which are the important genes for directing neuronal development, for example" said Daniela Di Bella, a postdoctoral fellow in the Arlotta lab and co-first author of the study.

For instance, it has been unclear exactly when the cortex's diversity of different neuron populations is established. "We found that the different flavors of neurons are decided during the neuron maturation process, rather than pre-established in their stem cells," Di Bella said.

The researchers also used their data to predict the underlying mechanism of how genetic mutation leads to defects in cortical development, finding which specific developmental steps are failing and which cells are being affected.

"We have created a uniquely comprehensive molecular atlas of the developing somatosensory cortex, and we are continuing to mine the data for more insights," said co-first author Ehsan Habibi. "Our goal is for our data to serve as a resource for the wider neuroscience community and inform how the field looks at brain development, both during normal and disease processes."

"These combined, extensive measurements provided us with a first dynamic view of the symphony of molecular events that unfold as this critical region of the brain is built in the embryo," said Arlotta, who is also an institute member in the Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research at the Broad Institute. "Researchers have been studying the process of development of the cerebral cortex for over a century, but the mechanistic events that govern how cells are made and how they interact to ultimately form functional circuit have remained elusive. As a field, we have historically looked at this complex developing tissue one cell type at a time, and investigated small numbers of genes for their roles in putting together pieces of this amazing puzzle. But the brain does not develop one cell type at the time -- it is truly a symphony in the sense that hundreds of cell types undergo development together, using ever-changing lanscapes of genes to form the adult tissue. Now imagine having for the first time the full 'recipe' of genes that any given cell class uses as its development unfolds. Imagine also gaining detailed knowledge of the 'codes of genes' that turn on or off as distinct lineages of cells separate from each other and get built. This type of overarching mechanistic knowledge offers an opportunity to study cortical development in a brand new way, looking at all cells and all genes. We never had information this complete before and I must admit that I stared at the data in awe, thinking about the type of discovery that it enables."

"Ten years ago, this study would not have been possible because the technologies either did not exist or were not mature enough yet," Regev said. "But with advances in single-cell and spatial transcriptomics, and new machine learning algorithms for large data analysis, we were able to map where cells develop, put those maps together, and watch development unfold like a movie over time. We could not only reconstruct the movie, but could also link that picture to a greater biological understanding of brain development. We hope this approach could one day help us better understand and treat diseases of the brain."

Arlotta added: "It is a pretty interesting movie -- one that I have looked forward to filming for most of my scientific career."

INFORMATION:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-06-24

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- Using an unusually well-preserved subfossil jawbone, a team of researchers -- led by Penn State and with a multi-national team of collaborators including scientists from the Université d'Antananarivo in Madagascar -- has sequenced for the first time the nuclear genome of the koala lemur (Megaladapis edwardsi), one of the largest of the 17 or so giant lemur species that went extinct on the island of Madagascar between about 500 and 2,000 years ago. The findings reveal new information about this animal's position on the primate family tree and how it interacted with its environment, which could help in understanding the impacts of past lemur extinctions on Madagascar's ecosystems.

"More than 100 species of lemurs live on Madagascar today, ...

2021-06-24

To better understand the role of bacteria in health and disease, National Institutes of Health researchers fed fruit flies antibiotics and monitored the lifetime activity of hundreds of genes that scientists have traditionally thought control aging. To their surprise, the antibiotics not only extended the lives of the flies but also dramatically changed the activity of many of these genes. Their results suggested that only about 30% of the genes traditionally associated with aging set an animal's internal clock while the rest reflect the body's response to bacteria.

"For ...

2021-06-24

COLUMBUS, Ohio - When the summer sun blazes on a hot city street, our first reaction is to flee to a shady spot protected by a building or tree.

A new study is the first to calculate exactly how much these shaded areas help lower the temperature and reduce the "urban heat island" effect.

Researchers created an intricate 3D digital model of a section of Columbus and determined what effect the shade of the buildings and trees in the area had on land surface temperatures over the course of one hour on one summer day.

"We can use the information from our model to formulate guidelines for community greening and tree planting efforts, and even where to locate buildings to maximize shading on other buildings and roadways," said Jean-Michel Guldmann, co-author of the study and ...

2021-06-24

A new tool to help conserve one of the UK's most threatened mammals has been released today, with the publication of the first high-quality reference genome for the European water vole. The genome was generated by scientists at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, in collaboration with animal conservation charity the Wildwood Trust, as part of the Darwin Tree of Life Project.

The genome, published today (24 June 2021) through Wellcome Open Research, is openly available as a reference for researchers seeking to assess water vole population genetics, better understand how the species has evolved and to manage reintroduction efforts.

The European water vole (Arvicola ...

2021-06-24

A team from Japan and the United States has identified the design principles for creating large "ideal" proteins from scratch, paving the way for the design of proteins with new biochemical functions.

Their results appear June 24, 2021, in Nature Communications.

The team had previously developed principles to design small versions of what they call "ideal proteins," which are structures without internal energetic frustration.

Such proteins are typically designed with a molecular feature called beta strands, which serve a key structural role for the molecules. In ...

2021-06-24

Our planet's strongest ocean current, which circulates around Antarctica, plays a major role in determining the transport of heat, salt and nutrients in the ocean. An international research team led by the Alfred Wegener Institute has now evaluated sediment samples from the Drake Passage. Their findings: during the last interglacial period, the water flowed more rapidly than it does today. This could be a blueprint for the future and have global consequences. For example, the Southern Ocean's capacity to absorb CO2 could decrease, which would in turn intensify climate change. The study has now been published in the journal Nature Communications.

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) is the world's strongest ocean ...

2021-06-24

Indonesia's volcanoes are among the world's most dangerous. Why? Through chemical analyses of tiny minerals in lava from Bali and Java, researchers from Uppsala University and elsewhere have found new clues. They now understand better how the Earth's mantle is composed in that particular region and how the magma changes before an eruption. The study is published in Nature Communications.

Frances Deegan, the study's first author and a researcher at Uppsala University's Department of Earth Sciences, summarises the findings.

"Magma is formed in the mantle, and the composition of the mantle under Indonesia used to be only partly known. ...

2021-06-24

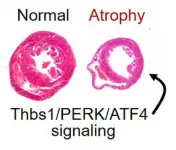

In many situations, heart muscle cells do not respond to external stresses in the same ways that skeletal muscle cells do. But under some conditions, heart and skeletal muscles can both waste away at fatally rapid rates, according to a new study led by experts at Cincinnati Children's.

The new findings, based on studies of mouse models, represent an important milestone in a long effort to prevent or even reverse cardiac atrophy, which can lead to fatal heart failure when the body loses large amounts of weight or experiences extended periods of weightlessness in space. Detailed findings were published online June 24, 2021, in Nature Communications.

"NASA is very interested in cardiac atrophy," says Jeffery Molkentin, PhD, Co-Director ...

2021-06-24

UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO

TORONTO, ON - A new study from researchers at the University of Toronto found that 63% of Canadians with migraine headaches are able to flourish, despite the painful condition.

"This research provides a very hopeful message for individuals struggling with migraines, their families and health professionals," says lead author Esme Fuller-Thomson, who spent the last decade publishing on negative mental health outcomes associated with migraines, including suicide attempts, anxiety disorders and depression. "The findings of our study have contributed to a major paradigm shift for me. There are important lessons to be learned from those who are flourishing."

A migraine headache, which afflicts ...

2021-06-24

A recent study finds states that exhibit higher levels of systemic racism also have pronounced racial disparities regarding access to health care. In short, the more racist a state was, the better access white people had - and the worse access Black people had.

"This study highlights the extent to which health care inequities are intertwined with other social inequities, such as employment and education," says Vanessa Volpe, corresponding author of the study and an assistant professor of psychology at North Carolina State University. "This helps explain why health inequities are so intractable. Tackling health care inequities will require us to address broader social systems that significantly benefit white people ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] A detailed atlas of the developing brain

Harvard and Broad researchers combine single-cell genomic technologies to map the mouse cortex