INFORMATION:

'Unlocking' the potential of viruses to fight cancer

Luxembourg Institute of Health (LIH) identifies 'key' protein allowing cancer-destroying viruses to enter tumor cells

2021-06-29

(Press-News.org) Researchers from the Laboratory of Oncolytic-Virus-Immuno-Therapeutics (LOVIT) at the LIH Department of Oncology (DONC) are working on the development of novel anticancer strategies based on oncolytic viruses, "good" viruses that can specifically infect, replicate in and kill cancer cells. In particular, the LOVIT team elucidated the mechanism through which the H-1PV cancer-destroying virus can attach to and enter cancer cells, thereby causing their lysis and death. At the heart of this process lie laminins, and specifically laminin γ1, a family of proteins on the surface of a cancer cell to which this virus binds, and which therefore act as the 'door' through which the virus enters the cells. The findings, which were published in the prestigious international journal Nature Communications, carry significant implications for the advancement of virus-based anticancer strategies and for the prediction of a patient's response to this innovative therapeutic approach.

Oncolytic viruses, such as the rat virus H-1PV, have the ability to selectively infect and kill tumour cells, inducing their lysis and stimulating an anticancer immune response, without however harming normal healthy tissues. Despite their notable clinical potential, their use as a standalone treatment does not currently result in complete tumour regression, mainly due to the varying degree of patient sensitivity and responsiveness. It is therefore important to be able to identify patients whose tumours display genetic characteristics that make them vulnerable to the virus and who are thus most likely to benefit from this novel anticancer therapy.

"In this context, we sought to elucidate the features of host cancer cells that enable oncolytic viruses to effectively infect and destroy them, focusing specifically on the factors required for cell attachment and entry", says Dr Antonio Marchini, leader of LOVIT and corresponding author of the publication.

Using a technique known as RNA interference, the research team progressively 'switched off' close to 7,000 genes of cervical carcinoma cells to detect those that negatively or positively modulate the infectious capacity of H-1PV. They thus identified 151 genes and their resulting proteins as activators and 89 as repressors of the ability of H-1PV to infect and destroy cancer cells. The team specifically looked at those genes that coded for proteins localised on the cell surface, in order to characterise their role in determining virus docking and entry. They found that a family of proteins called laminins, and particularly laminin γ1, play a crucial role in mediating cell attachment and penetration. Indeed, deactivating the corresponding LAMC1 gene in glioma, cervical, pancreatic, colorectal and lung carcinoma cells resulted in a significant reduction in virus cell binding and uptake, and in increased cancer cell resistance to virus-induced death. A similar effect was observed when switching off the LAMB1 gene encoding the laminin β1 protein.

"Essentially, laminins at the surface of the cancer cell are the 'door' that allows the virus to recognise its target, attach itself and penetrate into it, subsequently leading to its destruction. In particular, the virus interacts with a specific portion of the laminin, a sugar called sialic acid, which is essential for this binding and entry process and for infection", explains Dr Amit Kulkarni, first author of the publication.

The team went a step further and sought to assess the clinical implications of their findings for cancer patients. They found that laminins γ1 and β1 are differentially expressed across different tumours, being for instance overexpressed in pancreatic carcinoma and glioblastoma (GBM) cells compared to healthy tissues. Moreover, in brain tumours, their expression increases with tumour grade, with late-stage GBM displaying higher laminin levels than lower grade gliomas. Similarly, based on the analysis of 110 biopsies from both primary and recurrent GBM, the researchers reported significantly higher levels of laminins in recurrent GBM compared to primary tumours.

"These observations indicate that elevated laminin expression is associated with poor patient prognosis and survival in a variety of tumours, including gliomas and glioblastoma. The encouraging fact, however, is that cancers displaying high laminin levels are more susceptible to being infected and destroyed by the H-1PV virus and that patients with these tumours are therefore more likely to be responsive to this therapy", adds Dr Marchini.

These findings could lead to the classification of cancer patients according to their individual laminin expression levels, thereby acting as a biomarker that predicts their sensitivity and responsiveness to H-1PV-based anticancer therapies. This will in turn allow the design of more efficient clinical trials with reduced costs and approval times and, ultimately, the development of enhanced combinatorial treatments to tangibly improve patient outcomes.

The study was published in June 2021 in the renowned journal Nature Communications, with the full title "Oncolytic H-1 parvovirus binds to sialic acid on laminins for cell attachment and entry".

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Microstructure found in beetle's exoskeleton contributes to color and damage resistance

2021-06-29

Beetles are creatures with built-in body armor. They are tiny tanks covered with hard shells, also known as exoskeletons, protecting their soft, skeleton-less bodies inside. In addition to providing armored protection, the beetle's exoskeleton offers functions like sensory feedback and hydration control. Notably, the exoskeletons of many beetles are also brilliantly colored and patterned, which enhances visual communication with other beetles and organisms.

Ling Li, lead investigator and assistant professor in mechanical engineering, has joined colleagues from six other universities to investigate the interplay between mechanical and optical performance ...

Researchers identify muscle proteins whose quantity is reduced in type 2 diabetes

2021-06-29

Globally, more than 400 million people have diabetes, most of them suffering from type 2 diabetes.

Before the onset of actual type 2 diabetes, people are often diagnosed with abnormalities in glucose metabolism that are milder than those associated with diabetes. The term used to indicate such cases is prediabetes. Roughly 5-10% of people with prediabetes develop type 2 diabetes within a year-long follow-up.

Insulin resistance in muscle tissue is one of the earliest metabolic abnormalities detected in individuals who are developing type 2 diabetes, and the phenomenon is already seen in prediabetes.

In a collaborative study, researchers from the University of Helsinki, the ...

Researchers pinpoint unique growing challenges for soybeans in Africa

2021-06-29

URBANA, Ill. - Despite soybean's high protein and oil content and its potential to boost food security on the continent, Africa produces less than 1% of the world's soybean crop. Production lags, in part, because most soybean cultivars are bred for North and South American conditions that don't match African environments.

Researchers from the Soybean Innovation Lab (SIL), a U.S. Agency for International Development-funded project led by the University of Illinois, are working to change that. In a new study, published in Agronomy, they have developed methods to help breeders improve soybean cultivars specifically for African environments, with the intention of creating fast-maturing ...

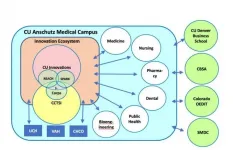

CU Anschutz called a 'case study' for commercializing medical breakthroughs

2021-06-29

A new study highlights the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus as an example of how an academic medical center can turn groundbreaking research into commercial products that improve patient care and public health.

The paper, published recently in the Journal of Clinical and Translational Science, focuses on the unique ecosystem at CU Anschutz responsible for these innovations. And it specifically details the campus's collaborative culture and how biomedical research is commercialized.

The campus has successfully turned academic research into a variety of products. CU Anschutz, for example, developed two vaccines for shingles, Zostavax and Shingrix, and ...

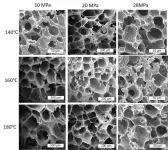

Turning plastic into foam to combat pollution

2021-06-29

WASHINGTON, June 29, 2021 -- Biodegradable plastics are supposed to be good for the environment. But because they are specifically made to degrade quickly, they cannot be recycled.

In Physics of Fluids, by AIP Publishing, researchers from the University of Canterbury in New Zealand have developed a method to turn biodegradable plastic knives, spoons, and forks into a foam that can be used as insulation in walls or in flotation devices.

The investigators placed the cutlery, which was previously thought to be "nonfoamable" plastic, into a chamber filled with carbon dioxide. ...

Dinosaurs were in decline before the end, according to new study

2021-06-29

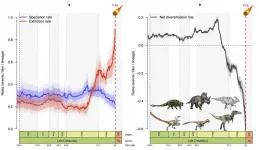

The death of the dinosaurs 66 million years ago was caused by the impact of a huge asteroid on the Earth. However, palaeontologists have continued to debate whether they were already in decline or not before the impact.

In a new study, published today in the journal Nature Communications, an international team of scientists, which includes the University of Bristol, show that they were already in decline for as much as ten million years before the final death blow.

Lead author, Fabien Condamine, a CNRS researcher from the Institut des Sciences de l'Evolution de Montpellier (France), said: "We looked at the six most abundant dinosaur families through the whole of the Cretaceous, spanning from 150 to 66 million ...

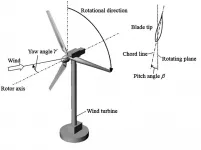

Steering wind turbines creates greater energy potential

2021-06-29

WASHINGTON, June 29, 2021 -- As wind passes through a turbine, it creates a wake that decreases the downstream average wind velocity. The faster the spin of the turbine blades relative to the wind speed, the greater the impact on the downstream wake profile.

For wind farms, it is important to control upstream turbines in an efficient manner so downstream turbines are not adversely affected by upstream wake effects. In the Journal of Renewable and Sustainable Energy, by AIP Publishing, researchers from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign show by designing controllers based on viewing ...

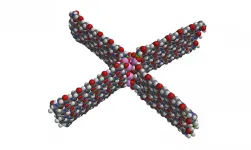

Polymers in meteorites provide clues to early solar system

2021-06-29

WASHINGTON, June 29, 2021 -- Many meteorites, which are small pieces from asteroids, do not experience high temperatures at any point in their existence. Because of this, these meteorites provide a good record of complex chemistry present when or before our solar system was formed 4.57 billion years ago.

For this reason, researchers have examined individual amino acids in meteorites, which come in a rich variety and many of which are not in present-day organisms.

In Physics of Fluids, by AIP Publishing, researchers from Harvard University show the existence of a systematic group of amino acid polymers across several members ...

This 5,000-year-old man had the earliest known strain of plague

2021-06-29

The oldest strain of Yersinia pestis--the bacteria behind the plague that caused the Black Death, which may have killed as much as half of Europe's population in the 1300s--has been found in the remains of a 5,000-year-old hunter-gatherer. A genetic analysis publishing June 29 in the journal Cell Reports reveals that this ancient strain was likely less contagious and not as deadly as its medieval version.

"What's most astonishing is that we can push back the appearance of Y. pestis 2,000 years farther than previously published studies suggested," says senior author Ben Krause-Kyora, head of the aDNA Laboratory at the University of Kiel in Germany. ...

Decline of dinosaurs underway long before asteroid fell

2021-06-29

Ten million years before the well-known asteroid impact that marked the end of the Mesozoic Era, dinosaurs were already in decline. That is the conclusion of the Franco-Anglo-Canadian team led by CNRS researcher Fabien Condamine from the Institute of Evolutionary Science of Montpellier (CNRS / IRD / University of Montpellier), which studied evolutionary trends during the Cretaceous for six major families of dinosaurs, including those of the tyrannosaurs, triceratops, and hadrosaurs. Using a novel statistical modelling method that limited bias associated with gaps in the fossil record, they demonstrated that, for dinosaurs 76 million years ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Bug beats: caterpillars use complex rhythms to communicate with ants

High-risk patients account for 80% of post-surgery deaths

Celebrity dolphin of Venice doesn’t need special protection – except from humans

Tulane study reveals key differences in long-term brain effects of COVID-19 and flu

The long standing commercialization challenge of lithium batteries, often called the dream battery, has been solved.

New method to remove toxic PFAS chemicals from water

The nanozymes hypothesis of the origin of life (on Earth) proposed

Microalgae-derived biochar enables fast, low-cost detection of hydrogen peroxide

Researchers highlight promise of biochar composites for sustainable 3D printing

Machine learning helps design low-cost biochar to fight phosphorus pollution in lakes

Urine tests confirm alcohol consumption in wild African chimpanzees

Barshop Institute to receive up to $38 million from ARPA-H, anchoring UT San Antonio as a national leader in aging and healthy longevity science

Anion-cation synergistic additives solve the "performance triangle" problem in zinc-iodine batteries

Ancient diets reveal surprising survival strategies in prehistoric Poland

Pre-pregnancy parental overweight/obesity linked to next generation’s heightened fatty liver disease risk

Obstructive sleep apnoea may cost UK + US economies billions in lost productivity

Guidelines set new playbook for pediatric clinical trial reporting

Adolescent cannabis use may follow the same pattern as alcohol use

Lifespan-extending treatments increase variation in age at time of death

From ancient myths to ‘Indo-manga’: Artists in the Global South are reframing the comic

Putting some ‘muscle’ into material design

House fires release harmful compounds into the air

Novel structural insights into Phytophthora effectors challenge long-held assumptions in plant pathology

Q&A: Researchers discuss potential solutions for the feedback loop affecting scientific publishing

A new ecological model highlights how fluctuating environments push microbes to work together

Chapman University researcher warns of structural risks at Grand Renaissance Dam putting property and lives in danger

Courtship is complicated, even in fruit flies

Columbia announces ARPA-H contract to advance science of healthy aging

New NYUAD study reveals hidden stress facing coral reef fish in the Arabian Gulf

36 months later: Distance learning in the wake of COVID-19

[Press-News.org] 'Unlocking' the potential of viruses to fight cancerLuxembourg Institute of Health (LIH) identifies 'key' protein allowing cancer-destroying viruses to enter tumor cells