(Press-News.org) Having friends may not only be good for the health of your social life, but also for your actual health--if you're a hyena, that is. Strong social connections and greater maternal care early in life can influence molecular markers related to gene expression in DNA and future stress response, suggests a new University of Colorado Boulder study of spotted hyenas in the wild.

Researchers found that more social connection and maternal care during a hyena's cub and subadult, or "teenage," years corresponded with lower adult stress hormone levels and fewer modifications to DNA, including near genes involved in immune function, inflammation and aging.

Published this week in Nature Communications, the study is one of the first to examine the association between early-life social environments and later effects on markers of health and stress response in wild animals.

"This study supports this idea that, yes, these early experiences do matter. They seem to have an effect at the molecular level and future stress response--and they're persistent," said lead author Zach Laubach, a postdoctoral fellow in ecology and evolutionary biology.

As far back as the 1950s and 60s, laboratory research has drawn associations between early life experiences in rodents, primates and humans and behavioral and physiological differences later in life. One landmark study published in 2004 also showed that the offspring of rats who got licked and groomed more by their mothers had less DNA methylation in a gene involved in regulating stress response. This kick-started the desire for more evidence that early life experiences could be related to patterns of modification in genes that influence stress and health.

One of the missing pieces in the past 20 years of research has been the ability to study this relationship in wild animals.

Enter the Masai Mara Hyena Project. Launched by co-authors Kay E. Holekamp and Laura Smale of Michigan State University in the 1980s, the project has collected more than 30 years of uninterrupted data on hyena populations in Maasai Mara National Reserve in Kenya. With this invaluable resource for studying animal behavior, evolution and conservation, the researchers have been able to utilize generations of data on individually known animals to draw connections between their interactions, behaviors and biological markers.

"Being able to measure behavior, physiology and molecular markers from the same population has allowed us to dig deeper into the possible mechanisms," said Laubach, who has been working with data from this project for nearly a decade.

Healthy stress response

Hyenas are ideal for such research as they are devoted mothers, have a strict social hierarchy and follow a consistent timeline for raising their cubs. Instead of giving birth to larger litters, they typically have one or two cubs at a time. Soon after birth, the cubs move into a communal den, where they are integrated into their peer group. For the next year, they still nurse and their mother licks and grooms them, but after that the cubs start to wander out of the den and, like teenagers, learn to start making their way in the world.

The researchers found that the more socially connected hyenas were during their teenage years, the lower their baseline stress hormone levels were later in life. This generally indicates a healthy stress response: Stress hormones can be elevated in an appropriate situation--like when being chased by a lion or a higher-ranking hyena--and when nothing's happening, levels of stress hormones remain low.

"So if you have more friends as a subadult, essentially, you have lower stress hormone levels as an adult," said Laubach. "This suggests that the type, timing and mechanisms that link these early life experiences with stress seem to be important not only in controlled laboratory settings but also in the wild, where animals are subject to natural variation."

In general, hyenas, like other vertebrates, benefit from the effects of stress hormones (e.g. cortisol) mobilizing energy, increasing their heart rate and shutting down non-essential functions, like digestion or reproduction, when escaping a dangerous situation. However, there are significant physical drawbacks to these processes occurring chronically, day after day in humans or other animals as the result of chronic stressors. That's why having a healthy stress response is so critical.

"We need these stress hormones because they are critical to a variety of basic biological functions," said Laubach. "And in the right context, like when escaping a predator, they can save your life. But when elevated chronically, these hormones can be detrimental to your health," said Laubach.

Time travel through DNA

The researchers also wanted to find out if the relationships between early life social experiences and how stress presents later in life is managed by molecular mechanisms.

To do this, Laubach and his co-authors measured and analyzed the level of care and interaction the animal received in early life and their associations with certain modifications to its DNA later in life. These modifications can, through a process known as DNA methylation, end up changing the expression of certain genes, which can in turn, affect an animal's physiology or behavior.

The researchers found that the maternal care hyenas received during their first year of life, as well as their social connections after den independence, corresponded to differences in DNA methylation levels.

"This echoes a growing body of epidemiological work which studies how the timing of an exposure affects a health outcome. The idea is that, as an organism develops, there are certain points in time, often referred to as sensitive periods, when an exposure has a larger and a more persistent effect than if that exposure occurred at a later point in time," said Laubach.

INFORMATION:

Additional authors on this paper include Julia R. Greenberg, Julie W. Turner and Kay E. Holekamp of Michigan State University and the Mara Hyena Project; Tracy M. Montgomery of Michigan State University, the Mara Hyena Project and the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior; Malit O. Pioon of the Mara Hyena Project; Maggie A. Sawdy, and Laura Smale of Michigan State University; Raymond G. Cavalcante, Karthik R. Padmanabhan and Claudia Lalancette of the University of Michigan; Bridgett vonHoldt of Princeton University; Christopher D. Faulk of the University of Minnesota; Dana C. Dolinoy of the University of Michigan and University of Michigan School of Public Health; and Wei Perng of the University of Colorado Denver.

The body's so-called good cholesterol may be even better than we realize. New research from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis suggests that one type of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) has a previously unknown role in protecting the liver from injury. This HDL protects the liver by blocking inflammatory signals produced by common gut bacteria.

The study is published July 23 in the journal Science.

HDL is mostly known for mopping up cholesterol in the body and delivering it to the liver for disposal. But in the new study, the researchers identified a special type of HDL called HDL3 that, when produced by the intestine, blocks gut bacterial signals ...

By analyzing peoples' visitation patterns to essential establishments like pharmacies, religious centers and grocery stores during Hurricane Harvey, researchers at Texas A&M University have developed a framework to assess the recovery of communities after natural disasters in near real time. They said the information gleaned from their analysis would help federal agencies allocate resources equitably among communities ailing from a disaster.

"Neighboring communities can be impacted very differently after a natural catastrophic event," said Dr. Ali Mostafavi, associate professor in the ...

Most people can expect to break close to two bones in their lifetime, but those with osteogenesis imperfecta -- also known as brittle bone disease -- can break hundreds of bones before they even hit puberty. And while healthy bones can break from a hard fall or a bad car wreck, there may not be an apparent reason at all with brittle bone disease.

Classified as a rare disease, osteogenesis imperfecta, or OI, affects 6-7 people out of every 100,000 live births and can range in severity depending on the specific mutation. And while there are currently few treatment options and no cure, ...

DURHAM, N.C. - Scientists at Duke University have developed a suite of four new tests that can be used to detect coal ash contamination in soil with unprecedented sensitivity.

The tests are specifically designed to analyze soil for the presence of fly ash particles so small other tests might miss them.

Fly ash is part of coal combustion residuals (CCRs) that are generated when a power plant burns pulverized coal. The tiny fly ash particles, which are often microscopic in size, contain high concentrations of arsenic, selenium and other toxic elements, many of which have been ...

According to the United Nations' telecommunications agency, 93% of the global population has access to a mobile-broadband network of some kind. With data becoming more readily available to consumers, there is also an appetite for more of it, and at faster speeds.

Ramy Rady, doctoral student in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at Texas A&M University, is working with Dr. Kamran Entesari, his faculty advisor and professor, and Dr. Christi Madsen, professor, to design a chip that can revolutionize the current data rate for processors and technologies such as smartphones, laptops, etc. Dr. Sam Palermo, ...

Since early 2019, researchers have been recording and analysing marsquakes as part of the InSight mission. This relies on a seismometer whose data acquisition and control electronics were developed at ETH Zurich. Using this data, the researchers have now measured the red planet's crust, mantle and core - data that will help determine the formation and evolution of Mars and, by extension, the entire solar system.

Mars once completely molten

We know that Earth is made up of shells: a thin crust of light, solid rock surrounds a thick mantle of heavy, viscous rock, which in turn envelopes a core consisting mainly of iron and ...

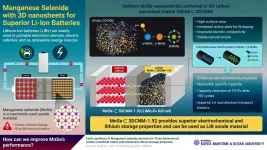

Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs), which are a renewable source of energy for electrical devices or electric vehicles, have attracted much attention as the next-generation energy solution. However, the anodes of LIBs in use today have multiple inadequacies, ranging from low ionic electronic conductivity and structural changes during the charge/discharge cycle to low specific capacity, which limits the battery's performance.

In search of a better anode material, Dr. Jun Kang of Korea Maritime and Ocean University, along with his colleagues from Pusan National University, Republic of Korea, END ...

July 22, 2021 - Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, more than 40 percent of nurses and other health care workers had risks associated with an increased likelihood of burnout, reports a survey study in the August issue of the American Journal of Nursing (AJN). The journal is published in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters Kluwer.

The study identifies risk factors for poor well-being as well as factors associated with greater resilience - which may reduce the risk of burnout for hands-on care providers, according to the new research by Lindsay Thompson Munn, RN, PhD, and colleagues of a North Carolina healthcare system. They write, "The insights ...

The University of Surrey has built an artificial intelligence (AI) model that identifies chemical compounds that promote healthy ageing - paving the way towards pharmaceutical innovations that extend a person's lifespan.

In a paper published by Nature Communication's Scientific Reports, a team of chemists from Surrey built a machine learning model based on the information from the DrugAge database to predict whether a compound can extend the life of Caenorhabditis elegans - a translucent worm that shares a similar metabolism to humans. The worm's shorter lifespan gave the researchers the opportunity to see the impact of the chemical compounds.

The AI singled ...

Houston Methodist Neurological Institute researchers from the department of neurosurgery shrunk a deadly glioblastoma tumor by more than a third using a helmet generating a noninvasive oscillating magnetic field that the patient wore on his head while administering the therapy in his own home. The 53-year-old patient died from an unrelated injury about a month into the treatment, but during that short time, 31% of the tumor mass disappeared. The autopsy of his brain confirmed the rapid response to the treatment.

"Thanks to the courage of this patient and his family, we were able to test and verify the potential effectiveness of the first noninvasive therapy ...