(Press-News.org) The body's first encounter with SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind COVID-19, happens in the nose and throat, or nasopharynx. A new study in the journal Cell suggests that the first responses in this battleground help determine who will develop severe disease and who will get through with mild or no illness.

Building on work published last year identifying SARS-CoV-2-susceptible cells, a team of collaborators at Boston Children's Hospital, MIT, and the University of Mississippi Medical Center comprehensively mapped SARS-CoV-2 infection in the nasopharynx. They obtained samples from the nasal swabs of 35 adults with COVID-19 from April to September 2020, ranging from mildly symptomatic to critically ill. They also got swabs from 17 control subjects and six patients who were intubated but did not have COVID-19.

"Why some people get more sick than others has been one of the most puzzling aspects of this virus from the beginning," says José Ordovás-Montañés, PhD, of Boston Children's, co-senior investigator on the study with Bruce Horwitz, MD, PhD of Boston Children's, Alex K. Shalek, PhD, of MIT and Sarah Glover, DO, of the University of Mississippi. "Many studies looking for risk predictors have looked for signatures in the blood, but blood may not really be the right place to look."

COVID-19's first battlefield: the nasopharynx

To get a detailed picture of what happens in the nasopharynx, the researchers sequenced the RNA in each cell, one cell at a time. (For a sense of all the work this entailed, each patient swab yielded an average of 562 cells.) The RNA data enabled the team to pinpoint which cells were present, which contained RNA originating from the virus -- an indication of infection -- and which genes the cells were turning on and off in response.

It soon became clear that the epithelial cells lining the nose and throat undergo major changes in the presence of SARS-CoV-2. The cells diversified in type overall. There was an increase in mucus-producing secretory and goblet cells. At the same time, there was a striking loss of mature ciliated cells, which sweep the airways, together with an increase in immature ciliated cells (which were perhaps trying to compensate).

The team found SARS-CoV-2 RNA in a a diverse range of cell types, including immature ciliated cells and specific subtypes of secretory cells, goblet cells, and squamous cells. The infected cells, as compared to the uninfected "bystander" cells, had more genes turned on that are involved in a productive response to infection.

A failed early immune response

The key finding came when the team compared nasopharyngeal swabs from people with different severity of COVID-19 illness:

In people with mild or moderate COVID-19, epithelial cells showed increased activation of genes involved with antiviral responses -- especially genes stimulated by type I interferon, a very early alarm that rallies the broader immune system.

In people who developed severe COVID-19, requiring mechanical ventilation, antiviral responses were markedly blunted. In particular, their epithelial cells had a muted response to interferon, despite harboring high amounts of virus. At the same time, their swabs had increased numbers of macrophages and other immune cells that boost inflammatory responses.

"Everyone with severe COVID-19 had a blunted interferon response early on in their epithelial cells, and were never able to ramp up a defense," says Ordovás-Montañés. "Having the right amount of interferon at the right time could be at the crux of dealing with SARS-CoV-2 and other viruses."

Boosting interferon responses in the nose?

As a next step, the researchers plan to investigate what is causing the muted interferon response in the nasopharynx, which evidence suggests may also occur with the new SARS-CoV-2 variants. They will also explore the possibility of augmenting the interferon response in people with early COVID-19 infections, perhaps with a nasal spray or drops.

"It's likely that, regardless of the reason, people with a muted interferon response will be susceptible to future infections beyond COVID-19," Ordovás-Montañés says. "The question is, 'How do you make these cells more responsive?'"

INFORMATION:

Other recent COVID-19 research at Boston Children's Hospital

Carly Ziegler, Vincent Miao, Andrew Navia, and Joshua Bromley of MIT and Harvard; Anna Owings of the University of Mississippi; and Ying Tang of Boston Children's Hospital were co-first authors on the paper. Funders include the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative DAF, the National Institutes of Health, the New York Stem Cell Foundation, the Richard and Susan Smith Family Foundation, the AGA Research Foundation, the Food Allergy Science Initiative, The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard.

About Boston Children's Hospital

Boston Children's Hospital is ranked the #1 children's hospital in the nation by U.S. News & World Report and is the primary pediatric teaching affiliate of Harvard Medical School. Home to the world's largest research enterprise based at a pediatric medical center, its discoveries have benefited both children and adults since 1869. Today, 3,000 researchers and scientific staff, including 9 members of the National Academy of Sciences, 23 members of the National Academy of Medicine and 12 Howard Hughes Medical Investigators comprise Boston Children's research community. Founded as a 20-bed hospital for children, Boston Children's is now a 415-bed comprehensive center for pediatric and adolescent health care. For more, visit our Answers blog and follow us on social media @BostonChildrens, @BCH_Innovation, Facebook and YouTube.

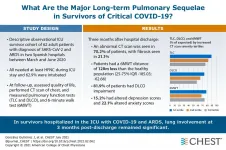

Glenview, Ill. - Published monthly, the journal CHEST® features peer-reviewed, cutting-edge original research in chest medicine: Pulmonary, critical care, sleep medicine and related disciplines. Journal topics include asthma, chest infections, COPD, critical care, diffuse lung disease, education and clinical practice, pulmonology and cardiology, sleep, and thoracic oncology.

The July issue of CHEST journal includes 85 articles, clinically relevant research, reviews, case series, commentary and more. Each month, the journal also offers complementary web and multimedia activities, ...

Elderly patients with neurological conditions are significantly more likely to develop delirium shortly after they are hospitalised.

A new study has discovered that a delayed transfer to a hospital floor is associated with greater short-term risk of delirium among patients aged 65 and over, and for those who arrive to the Emergency Department (ED) on days with higher risk of prolonged lengths of stay - found to be Sunday and Tuesday.

Delirium is an acute cognitive disorder characterised by altered awareness, attentional deficits, confusion, and disorientation. Current estimates of new-onset delirium highlight the fact that delirium overwhelmingly develops in medical settings (as high as 82 per cent in intensive care settings) compared ...

Electromagnetic (EM) waves in the terahertz (THz) regime contribute to important applications in communications, security imaging, and bio- and chemical sensing. Such wide applicability has resulted in significant technological progress. However, due to weak interactions between natural materials and THz waves, conventional THz devices are typically bulky and inefficient. Although ultracompact active THz devices do exist, current electronic and photonic approaches to dynamic control have lacked efficiency.

Recently, rapid developments in metasurfaces have opened new possibilities for the creation of high-efficiency, ultracompact THz ...

SAN FRANCISCO, CA--July 22, 2021--To speed up a chemical reaction, a chemist might place the reactants over a Bunsen burner. Adding heat increases the degree of random movements and collisions of particles, accelerating the reaction.

In cell biology, one important "reaction" is the transformation of stem cells into all the other cells in the body, a process known as differentiation. Gladstone Institutes researchers have now discovered a molecular mechanism that acts like a Bunsen burner to "turn up the heat" and accelerate differentiation.

However, instead of boosting temperature, this process amplifies random fluctuations ...

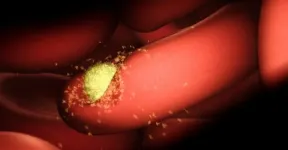

New York, NY (July 23, 2021) -- Mount Sinai researchers have developed a therapeutic agent that shows high effectiveness in vitro at disrupting a biological pathway that helps cancer survive, according to a paper published in Cancer Discovery, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research, in July.

The therapy is an engineered molecule, named MS21, that causes the degradation of AKT, an enzyme that is overly active in many cancers. This study laid out evidence that pharmacological degradation of AKT is a viable treatment for cancers with mutations in certain genes.

AKT is a cancer gene that encodes an enzyme that is frequently abnormally activated in cancer cells to stimulate tumor growth. Degradation of ...

Advanced technologies have been used to solve a long-standing mystery about why some people develop serious illness when they are infected with the malaria parasite, while others carry the infection asymptomatically.

An international team used mass cytometry - an in-depth way of characterising individual cells - and machine learning to discover 'immune signatures' associated with symptomatic or asymptomatic infections in people infected with the Plasmodium vivax parasite. This uncovered an unexpected role for immune T cells in protection against malaria, ...

How does a view of nature gain its gloss of beauty? We know that the sight of beautiful landscapes engages the brain's reward systems. But how does the brain transform visual signals into aesthetic ones? Why do we perceive a mountain vista or passing clouds as beautiful? A research team from the Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics has taken up this question and investigated how our brains proceed from merely seeing a landscape to feeling its aesthetic impact.

In their study, the research team presented artistic landscape videos to 24 participants. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), they measured the participants' brain activity as they viewed and rated the videos. Their findings have just been published in the ...

As Xi'an Jiaotong-Liverpool University researchers completed their research on coloured architectural concrete, they found a surprising result--green pigmented cement had impurities that produced porous, poor quality concrete. Meanwhile, red and blue pigments had little effect.

The research was conducted by Mehreen Heerah, a graduate of XJTLU's Department of Civil Engineering, Dr Graham Dawson of XJTLU's Department of Chemistry, and Isaac Galobardes of Mohammed VI Polytechnic University.

Pigmented architectural concrete is used as a visually appealing alternative to grey concrete, such as in Barcelona's Ciutat de la Justícia, explains Dr Dawson. As the demand for pigmented architectural concrete grows, so does the importance of this research.

Not easy ...

New research from the University of Otago debunks a long-held belief about our ancestors' eating habits.

For more than 60 years, researchers have believed Paranthropus, a close fossil relative of ours which lived about one to three million years ago, evolved massive back teeth to consume hard food items such as seeds and nuts, while our own direct ancestors, the genus Homo, is thought to have evolved smaller teeth due to eating softer food such as cooked food and meats.

However, after travelling to several large institutes and museums in South Africa, Japan and the ...

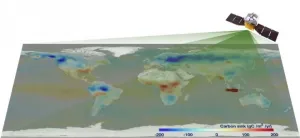

About six gigatons -- roughly 12 times the mass of all living humans -- of carbon appears to be emitted over land every year, according to data from the Chinese Global Carbon Dioxide Monitoring Scientific Experimental Satellite (TanSat).

Using data on how carbon mixes with dry air collected from May 2017 to April 2018, researchers developed the first global carbon flux dataset and map. They published their results in Advances in Atmospheric Sciences.

The map was developed by applying TanSat's satellite observations to models of how greenhouse gasses are exchanged among Earth's atmosphere, land, ...