(Press-News.org) Photos

Birds across the Americas are getting smaller and longer-winged as the world warms, and the smallest-bodied species are changing the fastest.

That's the main finding of a new University of Michigan-led study scheduled for online publication May 8 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The study combines data from two previously published papers that measured body-size and wing-length changes in a total of more than 86,000 bird specimens over four decades in North and South America. One study examined migrating birds killed after colliding with buildings in Chicago; the other looked at nonmigrating birds netted in the Amazon.

Though the two datasets are nonoverlapping in both species composition and geography, and the data were collected independently using different methods, the birds in both studies displayed similarly widespread declines in body size with concurrent increases in wing length.

Now, a new analysis of the combined data has revealed an even more striking pattern: In both studies, smaller bird species declined proportionately faster in body size and increased proportionately faster in wing length.

"The relationships between body size and rates of change are remarkably consistent across both datasets. However, the biological mechanism underlying the observed link between body size and rates of morphological change requires further investigation," said U-M ornithologist Benjamin Winger, one of the study's two senior authors, an assistant professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, and an assistant curator at the Museum of Zoology.

Both the Chicago and Amazonian studies attributed the reductions in species body size to increasing temperatures over the past 40 years, suggesting that body size may be an important determinant of species responses to climate change.

Even so, exactly why smaller-bodied species are changing faster remains an open question, according to the researchers.

It could be that smaller-bodied birds are adapting more quickly to evolutionary pressures. But the available data did not allow the U-M-led team to test whether the observed size shifts represent rapid evolutionary changes in response to natural selection.

"If natural selection plays a role in the patterns we observed, our results suggest that smaller bird species might be evolving faster because they experience stronger selection, are more responsive to selection, or both," said co-senior author Brian Weeks, an evolutionary ecologist at the U-M School for Environment and Sustainability.

"Either way, body size appears to be a primary mediator of birds' responses to contemporary climate change."

So, if larger-bodied birds are responding more slowly to global change, what's the prognosis for the coming decades, as temperatures continue to climb?

"Our results suggest that large body size could further exacerbate extinction risk by limiting the potential to adapt to rapid, ongoing anthropogenic change," said study lead author Marketa Zimova, a former U-M Institute for Global Change Biology postdoctoral researcher now at Appalachian State University.

"In contrast, the body-size effect on evolutionary rates might increase persistence of small taxa if their rapidly changing morphology reflects a faster adaptive response to changing conditions."

The new study analyzed data from 129 bird species: 52 migratory species breeding in North America and 77 South American resident species. The 86,131 specimens were collected over roughly the same period using different techniques.

The smallest bird among the Chicago species was the golden-crowned kinglet (Regulus satrapa) at an average size of 5.47 grams, and the largest was the common grackle (Quiscalus quiscula) at 107.90 grams. Among the Amazonian species, the fork-tailed woodnymph (Thalurania furcata) was the smallest at 4.08 grams, and the largest was the Amazonian motmot (Momotus momota) at 131.00 grams.

The North American dataset was derived from birds retrieved by staff and volunteers at Chicago's Field Museum after collisions with city buildings. For each of the 70,716 individuals, Field Museum ornithologist David Willard measured bill length, wing length, body mass and the length of a lower leg bone called the tarsus.

"The birds collected from window collisions in Chicago are providing insights into morphological changes related to the changing climate. It is extremely gratifying to see data from these birds analyzed for a better understanding of the factors driving these changes," said Willard, collections manager emeritus and a co-author of the new PNAS study.

The Amazonian dataset contains measurements of 15,415 nonmigratory birds captured with mist nets in the rainforest, measured, then released. Two measurements were consistently recorded throughout the study period: mass and wing length.

The large and complementary datasets provided a unique opportunity to test whether two fundamental organismal traits—body size and generation length—shaped the birds' responses to rapid environmental change.

Among biologists, it is broadly assumed that a species' generation length, defined as the average age of individuals producing offspring, is an important predictor of its ability to adapt to rapid environmental change.

Shorter-lived organisms that reproduce on relatively short time scales, such as mice, are predicted to evolve faster than creatures with longer generation lengths, such as elephants, because the mice have more frequent opportunities to make use of the random genetic mutations generated during reproduction.

The authors of the new PNAS study used statistical models to test the importance of both generation length and species body size in mediating rates of morphological change in birds.

After controlling for body size, they found no relationship between generation length and rates of change in the North American bird species. Generation-length data were not available for the South American birds, so they were not included in that part of the analysis.

At the same time, the new analysis showed that a species' mean body size was significantly associated with the rates of change measured in both the Chicago and Amazonian birds.

"Body size may be a valuable predictor of adaptive capacity and the extent to which contemporary evolution may reduce risk of extinction among species," the authors wrote.

In addition to Winger, Weeks, Zimova and Willard, the authors of the PNAS paper are Sean Giery of Pennsylvania State University, Vitek Jirinec of Integral Ecology Research Center and Ryan Burner of the U.S. Geological Survey.

The study was supported by funding from the Institute for Global Change Biology at the U-M School for Environment and Sustainability.

Study (available once the embargo lifts): Body size predicts the rate of contemporary morphological change in birds

END

Smallest shifting fastest: Bird species body size predicts rate of change in a warming world

2023-05-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NSU research into bacteria may lead to new ways of treating infections, improving human health

2023-05-08

FORT LAUDERDALE/DAVIE, Fla. – “Know thy self; know thy enemy” - Sun Tzu

That quote is from centuries ago, but it is applicable in so many ways. One example – new research from Nova Southeastern University (NSU) is understanding human infections and unlocking how bacteria “work together” making these infections much more difficult to treat. But it is understanding this symbiotic relationship – knowing thy enemy – that can lead to better ways to treat various ailments.

This new study was recently published by the scientific journal eLife, and can be found ONLINE.

“There are good bacteria and not so good ...

New study finds that fitterfly diabetes digital therapeutics program improves blood sugar levels and promotes weight loss in patients with Type 2 diabetes

2023-05-08

A new research study published in JMIR Diabetes evaluated the real-world effectiveness of the Fitterfly Diabetes CGM digital therapeutic program for the management of glycemic control and weight in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. The study led by Shilpa Joshi, Arbinder Singal, and colleagues found significant improvements in both blood glucose levels and weight management in participants enrolled in the 90-day program.

The Fitterfly Diabetes CGM program, delivered through the Fitterfly mobile app coupled with continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) technology, provides users with tailored recommendations on nutrition based on personalized ...

Novel Rutgers COVID vaccine may provide long-lasting protection

2023-05-08

Animal studies indicate that a new COVID-19 vaccine developed at Rutgers may provide more durable protection against SARS-CoV-2 and its emerging variants than existing vaccines.

“We need a better vaccine, one that provides years of robust protection with fewer booster shots against a variety of SARS-CoV-2 strains. Our data suggest this vaccine candidate might be able to do that,” said Stephen Anderson, associate professor of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry in SAS, resident member of the Rutgers Center for Advanced ...

Pollen production could impact climate change by helping clouds form

2023-05-08

For millions of people with seasonal allergies, springtime means runny noses, excessive sneezes and itchy eyes. And, as with many things, climate change appears to be making allergy season even worse. Researchers reporting in ACS Earth and Space Chemistry have shown that common allergen-producing plants ryegrass and ragweed emit more smaller, “subpollen particles” (SPPs) than once thought, yet climate would likely be most affected by their intact pollen grains, which can boost cloud formation.

In addition to annoying sinuses, pollen naturally functions as a ...

Plastic can drift far away from its starting point as it sinks into the sea

2023-05-08

Discarded or drifting in the ocean, plastic debris can accumulate on the water’s surface, forming floating islands of garbage. Although it’s harder to spot, researchers suspect a significant amount also sinks. In a new study in ACS’ Environmental Science & Technology, one team used computer modeling to study how far bits of lightweight plastic travel when falling into the Mediterranean Sea. Their results suggest these particles can drift farther underwater than previously thought.

From ...

Scintillating science: FSU researchers improve materials for radiation detection and imaging technology

2023-05-08

A team of Florida State University researchers has further developed a new generation of organic-inorganic hybrid materials that can improve image quality in X-ray machines, CT scans and other radiation detection and imaging technologies.

Professor Biwu Ma from the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry and his colleagues have developed a new class of materials that can act as highly efficient scintillators, which emit light after being exposed to other forms of high energy radiations, such as X-rays.

The team’s most recent study, published in Advanced Materials, is an improvement upon their previous research to develop better scintillators. The new design concept produces ...

Webb looks for Fomalhaut’s asteroid belt and finds much more

2023-05-08

Astronomers used NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope to image the warm dust around a nearby young star, Fomalhaut, in order to study the first asteroid belt ever seen outside of our solar system in infrared light. But to their surprise, the dusty structures are much more complex than the asteroid and Kuiper dust belts of our solar system. Overall, there are three nested belts extending out to 14 billion miles (23 billion kilometers) from the star; that’s 150 times the distance of Earth from the Sun. The scale of the outermost belt is roughly twice the scale of our ...

UCI researchers discover new drugs with potential for treating world’s leading causes of blindness in age-related and inherited retinal diseases

2023-05-08

Irvine, CA – May xx, 2023 – In a University of California, Irvine-led study, researchers have discovered small-molecule drugs with potential clinical utility in the treatment of age-related macular degeneration (AMD), diabetic retinopathy (DR), and retinitis pigmentosa (RP).

The study, titled, “Stress resilience-enhancing drugs preserve tissue structure and function in degenerating retina via phosphodiesterase inhibition,” was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“In this study, we introduce a new class of therapeutics called ‘Stress ...

First deaf, Black woman receives her PhD in a STEM discipline

2023-05-08

ST. LOUIS, MO - May 8, 2023 – Graduate student Amie Fornah Sankoh recently stood in front of 150 colleagues family and friends at the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center to defend her thesis, Investigating the Effects of Salicylic acid on Intercellular Trafficking via Plasmodesmata in Nicotiana benthamiana. Upon her successful defense, Dr. Amie Sankoh became the first Deaf, Black woman to receive a PhD in any STEM discipline.

Completing a PhD is a challenging undertaking for anyone; to do so without easy access to the kinds of verbal communication that hearing people ...

Microbubble macrophages track tumors #ASA184

2023-05-08

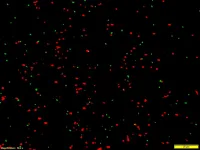

CHICAGO, May 8, 2023 – Macrophages, a type of white blood cell, defend the body by engulfing and digesting foreign particles, such as bacteria, viruses, and dead cells. The immune cells also tend to accumulate in solid tumors, so tracking them could enable new ways to detect cancer and the earliest stages of metastasis.

As part of the 184th Meeting of the Acoustical Society of America, Ashley Alva of the Georgia Institute of Technology will describe how attaching microbubbles to macrophages can create high-resolution and sensitive tracking images useful for disease diagnosis. Her presentation, “Tracking macrophages ...