(Press-News.org)

FU Qiaomei, a paleogeneticist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), received the UNESCO–AI Fozan International Prize for the Promotion of Young Scientists in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) on June 19 in Paris, France, for her “seminal work on the history of early humans in Eurasia, based on genetic lineage studies, which provides new insights on the early human history of Eurasia and perspectives on the evolution of human health.”

She was one of five young scientists from around the world to receive the prize, alongside researchers from Argentina, Cameroon, Egypt, and Serbia. The laureates were selected from 2,500 candidates worldwide.

The UNESCO–Al Fozan International Prize for the Promotion of Young Scientists is financially supported by the Al Fozan Foundation in Saudi Arabia. This is the first time the biennial prize has been awarded. It recognizes achievements that support capacity building, the development of scientific careers, and socioeconomic development at the national, regional, and global levels.

The prize is awarded to five laureates from the five geographic regions of UNESCO, to encourage youth participation in STEM, in particular women and girls. It is launched to strengthen research and international cooperation in STEM fields in order to confront the global challenges addressed by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Born in 1983, FU is now a professor and director of the Molecular Paleontology Laboratory at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP) of CAS in Beijing. Her research focuses on providing insight into the genetic history of humans, including who lived when and where, and how they moved and interacted over time.

“Past humans shaped the genetic patterns of humans today, influencing our health and adaptation to diverse environments,” said FU. “I was a curious child, fascinated by mysteries of the past and how they shape our present and future. That curiosity led me to pursue a career in genetics, in the field of ancient DNA.”

Her dedication to evolutionary genetics and population genetics has yielded significant insights into the history and biology of humans in Eurasia and innovative developments in related research methodologies.

Among her achievements, FU has retrieved ancient DNA from past human remains and sediments to construct an evolutionary map of Eurasian (especially East Asian) populations over the past 100,000 years.

FU also led a team that decoded the world’s and East Asia’s earliest modern human genomes, unveiled many new insight into the genetic exchange between archaic and modern humans, and deeply elucidated the dynamics of East Asians over the past 40,000 years. In doing so, FU and her team have filled important gaps in human history and pioneered new methods for expanding the geographic and temporal scope of ancient DNA acquisition worldwide.

Some of FU’s research has investigated population changes and adaptations during the Ice Age in Eurasia. For example, the widely distributed population related to the Tianyuan Cave individual was found to have disappeared by the end of the Last Glacial Maximum (19,000 years ago). Subsequently, mutations in the EDAR gene emerged that are associated with typical features unique to East Asia such as thicker hair and more sweat glands, reflecting the influence of genetic selection in low ultraviolet environments.

“Ancient DNA research has provided insight into our biological makeup, with important implications,” said FU. “With ancient DNA, we can study the genetic makeup of past populations to better understand the origins of diseases and motivate development of new treatments.”

FU also discovered many unique, unknown human lineages whose ancestries are not found today. In addition, she showed how some other ancestral lineages, such as northern and southern East Asians, greatly contributed to the genetic makeup of present-day East Asians, Austronesians and Native Americans.

These results reveal Eurasia’s unique and unknown human diversity and illuminate how different ancestries have shaped the genetic makeup and adaptative traits of humans today.

“Our past guides how we face the challenges of the future,” said FU.

To date, FU has authored 63 publications in international SCI journals, among which 36 were published as the first or corresponding author including three in Nature, four in Science and three in Cell.

FU has also won a series of other recognitions in her career. She was selected as one of “Ten Science Stars of China” by Nature magazine for her success in promoting the understanding of human evolution. She also received the “17th Award for Young Women in Science” from the National Commission of The People’s Republic of China for UNESCO as well as the “Tan Kah Kee Young Scientist Award in Life Sciences 2022” from the Tan Kah Kee Science Award Foundation, among other honors.

END

Researchers have demonstrated how carbon dioxide can be captured from industrial processes – or even directly from the air – and transformed into clean, sustainable fuels using just the energy from the Sun.

The researchers, from the University of Cambridge, developed a solar-powered reactor that converts captured CO2 and plastic waste into sustainable fuels and other valuable chemical products. In tests, CO2 was converted into syngas, a key building block for sustainable liquid fuels, and plastic bottles were converted into glycolic acid, which is widely used in the cosmetics industry.

Unlike earlier tests ...

A key challenge in neuroscience is to understand how the brain can adapt to a changing world, even with a relatively static anatomy. The way the brain’s areas are structurally and functionally related to each other – its connectivity – is a key component. In order to explain its dynamics and functions, we also need to add another piece to the puzzle: receptors. Now, a new mapping by Human Brain Project (HBP) researchers from the Forschungszentrum Jülich (Germany) and Heinrich-Heine-University Düsseldorf (Germany), in collaboration with scientists from the University of Bristol (UK), ...

In the age of dinosaurs, many marine reptiles had extremely long necks compared to reptiles today. While it was clearly a successful evolutionary strategy, paleontologists have long suspected that their long-necked bodies made them vulnerable to predators. Now, after almost 200 years of continued research, direct fossil evidence confirms this scenario for the first time in the most graphic way imaginable.

Researchers reporting in the journal Current Biology on June 19 studied the unusual necks of two Triassic ...

Receptor patterns define key organisational principles in the brain, scientists have discovered.

An international team of researchers, studying macaque brains, have mapped out neurotransmitter receptors, revealing a potential role in distinguishing internal thoughts and emotions from those generated by external influences.

The comprehensive dataset has been made publicly available, serving as a bridge linking different scales of neuroscience - from the microscopic to the whole brain.

Lead author Sean Froudist-Walsh, ...

People who owned black-and-white television sets until the 1980s didn’t know what they were missing until they got a color TV. A similar switch could happen in the world of genomics as researchers at the Berlin Institute of Medical Systems Biology of the Max Delbrück Center (MDC-BIMSB) have developed a technique called Genome Architecture Mapping (“GAM”) to peer into the genome and see it in glorious technicolor. GAM reveals information about the genome’s spatial architecture that is invisible to scientists using solely Hi-C, a workhorse tool developed in 2009 to study DNA interactions, reports a new study in Nature Methods by the Pombo lab.

“With ...

Scientists have long struggled to find the best way to present crucial facts about future sea level rise, but are getting better at communicating more clearly, according to an international group of climate scientists, including a leading Rutgers expert.

The consequences of improving communications are enormous, the scientists said, as civic leaders actively incorporate climate scientists’ risk assessments into major planning efforts to counter some of the effects of rising seas.

Writing in Nature Climate Change, the scientists ...

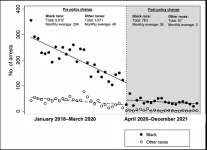

Ann Arbor, June 19, 2023 – De facto decriminalization of drug possession may be a good first step in addressing the disproportionate impact of an overburdened United States criminal justice system on the Black community. According to a new study in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, published by Elsevier, this strategy was associated with significant and sustained reductions in low-level arrests. These arrests too often prevent drug users from obtaining needed treatments and services. The findings also suggest that while these policies may effectively reduce the overall arrest toll, striking disparities persist in how police are applying the directives across racial ...

Embargoed until 8am Eastern Time on Monday, June, 19, 2023

DALLAS, June 19, 2023 — Constant or chronic stress can affect overall well-being and may even impact heart health. Chronic stress can lead to increased blood pressure, heart rate and inflammation, which can contribute to developing chronic diseases.[1] The American Heart Association, the leading global voluntary health organization dedicated to fighting heart disease and stroke for all, today launches a new campaign to help the Hispanic/Latino community protect its overall well-being by addressing common stressors that ...

How do asset markets work? Which stocks behave similarly? Economists, physicists, and mathematicians work intensively to draw a picture but need to learn what is happening outside their discipline. A new paper now builds a bridge.

In a new study, researchers of the Complexity Science Hub highlight the connecting elements between traditional financial market research and econophysics. "We want to create an overview of the models that exist in financial economics and those that researchers in physics and mathematics have developed ...

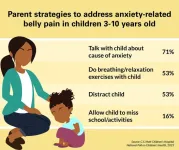

ANN ARBOR, Mich. – Tummy aches are common among kids, with one in six parents in a new national poll saying their child experiences them at least once a month.

But not all parents seek professional advice when belly pain becomes a regular occurrence and just one in three are sure they’d know when it might be a sign of a serious problem, according to the University of Michigan Health C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital National Poll on Children’s Health.

“Tummy complaints are common among children. This type of pain may be a symptom for a range of health issues, but it can be difficult to know if it’s ...