(Press-News.org) Giant dust storms in the Gulf of Alaska can last for many days and send tonnes of fine sediment or silt into the atmosphere, and it is having an impact on the global climate system, say scientists.

The storms are so extensive they can be seen by satellites orbiting the Earth. An image captured by the Landsat satellite in 2020 shows dust blowing out of the valley and over Alaska’s south coast.

Exactly how the dust may be influencing the global climate system is not yet clear, although new research from the University of Leeds and the National Centre for Atmospheric Science suggests the effect is bigger than previously thought.

How ice forms in clouds

At a low enough temperature, the silt - microscopic fragments of rock, minerals and vegetation - act as ice nucleating particles, which encourage the formation of ice crystals in clouds.

Whether ice formation in clouds will add to global warming or help cool the planet depends on how much ice they contain, how many ice nucleating particles are present and the nature of those particles.

In a paper published today -(Wednesday, Aug 16) - in the journal Science Advances, the research team argue that more research is needed to understand the role that dust plays in the complex global climate system.

Research has focussed on Saharan dust

Previous research has focused on dust particles whipped up into the atmosphere from storms in the Sahara and across Africa and Asia, all of which are at mid to low latitudes and involve dust generated from desert environments.

The researchers at Leeds took a different approach and decided to look at a high-latitude source of dust. They analysed dust coming from the Copper River Valley on the south coast of Alaska, which extends for more than 275 miles. The river is estimated to transport 70 million tonnes of glacial sediment every year.

During periods of low water - in the summer and autumn - the silt is picked up by winds and carried over hundreds of miles across north America, reaching altitudes where it can cause ice formation in clouds.

Unlike the dust from Sahara, however, dust particles from the Copper Valley River will contain a greater volume of biological material, deposited by the rich vegetation and wildlife that live in the region.

Ice formation in clouds

Dust particles in the atmosphere are important agents in ice formation.

In the absence of dust, water in clouds can remain in liquid form even though temperatures may be well below freezing.

Professor Benjamin Murray, an Atmospheric Scientist in the School of Earth and Environment at Leeds who supervised the study, said: “Only a small fraction of the dust particles in the atmosphere has the capacity to nucleate ice and we are only just starting to understand their sources and global distribution.

“Whether a cloud becomes more or less reflective of sunlight depends on how much ice is in them, so we need to be able to understand and quantify the various sources of ice-nucleating particles around the globe.

“At present, climate models tend not to represent these high-latitude sources of dust, but our work indicates that we need to.”

During the investigation, Sarah Barr and Bethany Wyld, doctoral researchers in the School of Earth and Environment at Leeds, collected samples during dust storms. The material was later analysed in the laboratory and compared to the types of dust particles that originate from desert environments.

They found that the particles from Alaska were more effective in forming ice than the dust that comes from the Sahara, driven by the presence of microscopic fragments of biogenic substances, particles that would have been produced by living organisms.

In contrast, particles of a mineral called potassium feldspar are believed to be the main ice nucleating agent in dust from the Sahara and locations in mid to low-level latitudes.

Ms Barr, the lead author of the paper, said: “We knew that deserts like the Sahara are very important at supplying ice-nucleating particles to the atmosphere, but this paper shows that river deltas like the Copper River Valley are also very important.

“Huge quantities of dust are emitted from places like the Copper River, and we need to understand these emissions to improve our climate models.”

The paper, Southern Alaska as a source of atmospheric mineral dust and ice-nucleating particles, is published in Science Advances and can be downloaded from the following URL when the embargo lifts https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adg3708

END

END

What role do dust storms play in the world’s climate?

2023-08-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

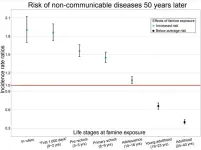

Children and adolescents of the 1959-61 Chinese famine: Survivors face increased risk of non-communicable diseases 50 years later, with those exposed in utero or under age 2 at double the risk

2023-08-16

Children and adolescents of the 1959-61 Chinese famine: Survivors face increased risk of non-communicable diseases 50 years later, with those exposed in utero or under age 2 at double the risk.

####

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/globalpublichealth/article?id=10.1371/journal.pgph.0002161

Article Title: Exposure to the 1959–1961 Chinese famine and risk of non-communicable diseases in later life: A life course perspective

Author Countries: Switzerland, UK

Funding: Mengling Cheng acknowledges funding from the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research “LIVES - Overcoming vulnerability: ...

The evolution of complex grammars

2023-08-16

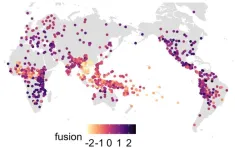

Languages around the world differ greatly in how many grammatical distinctions they make. This variation is observable even between closely related languages. The speakers of Swedish, Danish, and Norwegian, for example, use the same word hunden, meaning "the dog", to communicate that the dog is in the house or that someone found the dog or gave food to the dog. In Icelandic, on the other hand, three different word forms would be used in these situations, corresponding to the nominative, accusative, and dative case respectively: hundurinn, hundinn, and hundinum.

This grammatical distinction in the case system, along with many others, sets Icelandic apart ...

DOE’s Office of Science is now accepting applications for Office of Science Graduate Student Research (SCGSR) Awards

2023-08-16

Washington, D.C. - The Department of Energy’s (DOE) Office of Science is pleased to announce that the Office of Science Graduate Student Research (SCGSR) program is now accepting applications for the 2023 Solicitation 2 cycle. Applications are due on November 8, 2023, at 5:00 pm ET.

SCGSR application assistance workshops will be held on Thursday, September 14, 2023, 2:00 PM – 3:30 PM ET and Tuesday, October 10, 2023, 2:00 PM – 4:30 PM ET. The first workshop will provide a general overview of the program and the application requirements and will include a time for discussing potential research topics ...

Occupational safety and health training program grant renewed

2023-08-16

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, a division of the National Institutes of Health, awarded a $750,000 training program grant to researchers at the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health to support master’s students in the Industrial Hygiene Program.

Industrial hygiene is the art and science devoted to the anticipation, recognition, evaluation and control of workplace hazards. It focuses on worker protection from hazards that could include chemical, physical, biological, radiological and ergonomic agents.

“Occupational injury and illness affect millions of workers and their families every year and are tremendous ...

Inaugural theme issue: Precision public health from online Journal of Public Health Informatics

2023-08-16

Online Journal of Public Health Informatics (OJPHI) Editor-in-Chief: Edward K Mensah PhD, MPhil and theme editor Nsikak Akpakpan MD, PhD welcome submissions to a special theme issue examining "Precision Public Health."

The inaugural issue of the Online Journal of Public Health Informatics under the JMIR Publications platform will feature articles on precision public health, a technology-enhanced, data-driven targeted approach to public health practice and research.

The current special issue invites articles in the following as well ...

UC Irvine scientists say deepening Arctic snowpack drives greenhouse gas emissions

2023-08-16

Irvine, Calif., Aug. 16, 2023 — Human-caused climate change is shortening the snow cover period in the Arctic. But according to new research led by Earth system scientists at the University of California, Irvine, some parts of the Arctic are getting deeper snowpack than normal, and that deep snow is driving the thawing of long-frozen permafrost carbon reserves and leading to increased emissions of greenhouse gasses like carbon dioxide and methane.

“It is the first long-term experiment where we directly measure the mobilization of ancient carbon year-round to show that deeper snow has the possibility to rather ...

Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation awards $3.9 million to exceptional early-career scientists

2023-08-16

The Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation has named 13 new Damon Runyon Fellows, exceptional postdoctoral scientists conducting basic and translational cancer research in the laboratories of leading senior investigators. This prestigious Fellowship encourages the nation’s most promising young scientists to pursue careers in cancer research by providing them with independent funding to investigate cancer causes, mechanisms, therapies, and prevention. In July 2023, the Board of Directors announced a 15% ...

Assessing controls on ocean productivity – from space

2023-08-16

Phytoplankton determine how much life the ocean is able to support and play a role in controlling atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations, thereby regulating our climate. These tiny marine plants depend on sunlight as well as nutrients to thrive – including elements such as iron or nitrogen that can be brought to the ocean surface by currents and upwelling.

To understand phytoplankton nutrient limitations in the ocean, scientists typically conduct experiments during research expeditions at sea. However, this approach documents only a tiny fraction of the ocean at a certain point in time. Therefore, an international team of researchers tested if a signal detected by satellites in ...

Medications for chronic diseases affect the body’s ability to regulate body temperature, keep cool

2023-08-16

Medications to treat various chronic diseases may hinder the body’s ability to lose heat and regulate its core temperature to optimal levels. The loss of effective thermoregulation has implications for elderly people receiving treatment for illnesses like cancer, cardiovascular, Parkinson’s disease/dementia and diabetes, particularly during hot weather, according to a review by a team of scientists from various institutions in Singapore.

The group, led by Associate Professor Jason Lee from the Human Potential Translational Research Programme at the Yong Loo Lin School of ...

New leaf-tailed gecko from Madagascar is a master of disguise

2023-08-16

Leaf-tailed geckos are masters of camouflage. Some species have skin flaps around the whole body and head, as well as flattened tails. During the day, they rest head-down on tree trunks with these skin flaps spread out, and blend seamlessly into their surroundings, making them nearly impossible to spot. At night, they awaken to prowl the fine branches of the understory looking for invertebrate prey.

“When we first discovered this species in 2000, we already suspected it might be new to science,” says Dr Frank Glaw, curator of herpetology at the Bavarian State Collection of Zoology, lead author on the study. “But ...