What does an asparagus have in common with a vanilla orchid? Not much, if you are just looking at the two plants’ appearances. However, when you look inside - their leaves are more similar than you would think – as revealed by the composition of their cell walls.

By studying plant cell walls – which are to plants what skeletons are to humans – we can reveal the composition of how leaves and stems of plants are actually constructed. This is exactly what a team of University of Copenhagen researchers has done, in a large comprehensive study. In doing so, they have created something truly novel: a large "reference catalogue" of plant cell wall compositions from 287 species, broadly representing the entire plant kingdom.

"Flowering plants have succeeded in adapting to the most unwelcoming and harshest environments in the world, in part due to the construction of their cell walls. They provide the plants with both mechanical structure and ensure the internal transport of water. Plant cell walls are composed of many different carbohydrates, that each have a unique structure and function – you can think of them like toy building blocks." says botanist Louise Isager Ahl from the Natural History Museum of Denmark, and continues:

"Although humans rely heavily on plants and their carbohydrates for food, building materials, clothing and medicine, our knowledge of their fine structure is still quite limited. We know that carbohydrates are some of the most complex chemical structures in nature, but how they are assembled, how they work and how they have evolved over the past several million years is still largely unknown."

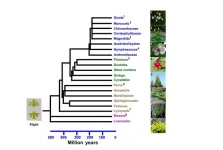

By analysing leaf and stem tissues from 287 different plant species, the researchers investigated the connection between the ultra-complex plant carbohydrates and their evolutionary history, growth forms and habitats. The species included in the study represent the most important evolutionary branches of the plant tree of life, from algae to vascular plants.

Genetic heritage more influential than environment

The researchers' hypothesis was that growth form and habitat would also affect plant cell wall structure. They expected, for example, to find similarities in the cell wall composition between species that were genetically distant but living in the same environment. This turned out not to be the case:

"As an example, in a typical Danish beech forest, you will find beech trees, anemones, various grasses, and other plants. Since they share the same habitat, it would be easy to think that their construction is also similar. However, our analyses show that the carbohydrate compositions of their cell walls are vastly different. And when we compare carbohydrate compositions with the plants' family history, habitat and growth form, we can see that it is primarily their family history that determines their individual structures," explains Louise Isager Ahl.

"The carbohydrate composition of a plant is thereby more closely related to where it is placed in a family tree than to its habitat and growth form. Here, heritage plays a more important role than environment," adds Professor Peter Ulvskov from the Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences.

Conversely, this also means that species that morphologically resemble each other or live in the same type of habitat can be constructed in very different ways. One good example of this relates to a pair of succulents studied by the scientists.

"Among others, we examined two succulent species, the jade plant (Crassula ovata) and jade necklace (Peperomia rotundifolia), both are common living room plants where the leaves resemble one another. However, they belong to two different families, and when we look at their carbohydrates, it turns out that the two plants are built very differently too," says Louise Isager Ahl.

Targeted plant breeding

The scientists hope that others will make use of their large dataset, which is freely available, together with their recently published article in the journal Plant, Cell & Environment. The catalogue of cell wall compositions could, for example, be used as a starting point for targeted breeding of crop plants.

"Even though the cell walls of plants are an important component in our food, animal feed, textiles and other materials, we have yet to target our breeding of cultivated plants to improve their cell wall properties. For example, cell walls determine to a large extent the digestibility of plant material. Targeted breeding of cell walls could increase both the quality and sustainability of animal feed. Now there is a catalogue to start from," says Peter Ulvskov.

Furthermore, the researchers believe that the dataset is ideal when it comes to research into climate-resilient plants.

"Our data can be used as an encyclopedia or reference database for researchers when they, for example, want to plan a study on a plant group they have not previously worked on. For example if you want to study how plant species in the rain forest, desert or on the heath react to environmental influences such as drought, high CO2 levels or floods – the dataset can be used as a benchmark," says Louise Isager Ahl.

This type of knowledge is important because climatic changes will probably change plant habitats:

"All of the climatic and environmental changes that we are now facing are challenging the planet's plants, and thus humans as well. Because we are deeply dependent on how plants function. If we are going to develop more resilient plants, it is important that we understand the mechanisms by which they survive or succumb. Here, understanding their building blocks, in the form of cell walls and carbohydrates plays a key role," concludes Peter Ulvskov.

ABOUT THE STUDY

The researchers analysed leaf and stem tissue from 287 specially selected plant species. The species represent both the main evolutionary branches of the plant kingdom, but also adaptations to a variety of habitats. The samples were examined using the MAPP (microarray polymer profiling) method, which provided unique carbohydrate (polysaccharide) compositions for both leaf and stem material. This data was then linked to the developmental history of the plants and their respective habitats.

Plant materials were collected both in nature, primarily on the island of Zealand, Demark, and from the University of Copenhagen’s various collections at the Natural History Museum of Denmark’s Botanical Garden, university greenhouses at the Frederiksberg Campus and the Arboretum in Hørsholm.

The study’s research article has been published in the journal Plant, Cell & Environment.

The researchers behind the study are: Jonatan U. Fangel, Niels Jacobsen, Jozef Mravec and Peter Ulvskov from the Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences; Louise Isager Ahl from the Natural History Museum of Denmark; Klavs Martin Sørensen and Søren Balling Engelsen from the Department of Food Science; Cassie Bakshani and William Willats from Newcastle University, UK and Maria Dalgaard Mikkelsen from the Technical University of Denmark (DTU).

The study is supported by the Villum Foundation. END