(Press-News.org) A new study in mice shows that replacement of a dysfunctional gene could prolong survival in some people with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC), a rare inherited disorder in which the muscular walls of the heart progressively weaken and put patients at risk of dangerous irregular heartbeats.

The investigational treatment targets the loss of function of a gene implicated in many cases of ARVC, plakophilin-2 (PKP2). The PKP2 gene provides instructions for making a protein that holds heart tissues together. When the gene — one of several thought to contribute to the disease —is defective and fails to make a functional protein, fibrous and fatty tissue builds up within the heart’s walls, causing them to weaken. The heart can also beat irregularly without any warning and sometimes stops working. While current therapies can help restore the heart’s normal rhythm and control symptoms, they fail to provide a cure.

In a collaboration between researchers at NYU Grossman School of Medicine and scientists at Rocket Pharmaceuticals (a biotechnology company), the new work revealed that untreated mice engineered to lose PKP2 gene function died within six weeks after the gene was silenced. However, all but one of those that received a single dose of a gene therapy, carrying the normal version of the gene, lived for more than five months. Mice that received the replacement gene also saw a 70% to 80% reduction in fibrous tissue buildup, depending on the dose.

“Our findings offer experimental evidence that gene therapy targeting plakophilin-2 can interrupt the progression of a deadly heart condition,” says study co-lead author Chantal van Opbergen, PhD, a postdoctoral research fellow at NYU Langone Health.

According to the study authors, the most advanced stages of ARVC are marked by irreversible heart damage, sometimes requiring a heart transplant. Researchers have long sought to slow the disease and prevent as much tissue loss as possible.

In earlier research from the NYU Langone team, the authors explored the mechanisms by which defects in the PKP2 gene can cause the unexpected occurrence of a life-threatening irregular heartbeat (arrhythmias), similar to that observed in some patients with ARVC. A report on their latest investigation on the effectiveness of gene therapy as a means of preventing or halting the disease in an animal model of PKP2 deficiency published online Jan. 30 in the journal Circulation: Genomic and Precision Medicine.

For the new study, the team used a mouse model of ARVC in which the genetic makeup was altered to render the PKP2 gene not functional. For proof-of concept in the present work , they used an adeno-associated viral vector as the delivery mechanism to transfer the healthy gene into the cardiac cells, thereby delivering the needed PKP2 protein therapy.

These viral vectors are small, non-replicating particles that ferry the desired gene into target cells by taking advantage of their natural infection process, namely their ability to invade a cell and take up residence there. However, unlike infectious viruses, the viral vectors do not multiply after their genetic material is transferred to the heart cells, which —with the healthy gene in place — now produce the normal protein. Rocket Pharmaceuticals designed and developed the viral vector that was used in the study.

According to the findings, the experimental treatment reduced episodes of arrythmia in the mice by as much as 50%, slowed the deterioration of the heart’s walls, and maintained their ability to pump blood effectively.

“These results suggest that this gene-therapy method may combat arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy in both early and more advanced stages of the condition,” said study co-senior author Mario Delmar, MD, PhD. Delmar is the Patricia M. and Robert H. Martinsen Professor of Cardiology in the Department of Medicine at NYU Langone Health and a professor in its Department of Cell Biology.

“Such promising findings in animal models pave the way towards exploring this treatment option in humans,” said study co-senior author and cardiologist Marina Cerrone, MD.

Based in part on the current study data, Rocket Pharmaceuticals has initiated a Phase 1 clinical trial to test the safety of the experimental treatment in ARVC patients with disease-causing PKP2 mutations, notes Cerrone, a research associate professor in the Department of Medicine at NYU Langone.

That said, Cerrone cautions that while targeting PKP2 affects one of the most common causes of ARVC, further experiments will be needed to correct other genetic mutations known to contribute to the disease.

In addition to Opbergen, Delmar, and Cerrone, other NYU Langone investigators involved in the study are Grace Chen, MS, and Mingliang Zhang, PhD. Other study authors include Chester Sacramento, PhD; Katie Stiles, PhD; Vartika Mishra, PhD; Esther Frenk, BA; David Ricks, PhD; Paul Yarabe, MBA; and Jonathan Schwartz, MD; at Rocket Pharmaceuticals Inc. in Cranbury, N.J. Bitha Narayanan, PhD, and Christopher D. Herzog, PhD, also of Rocket Pharmaceuticals, served as study co-lead author and co-senior author, respectively.

Media Inquiries:

Shira Polan

Phone: 212-404-4279

shira.polan@nyulangone.org

END

Gene-based therapy may slow development of life-threatening heart condition

2024-01-30

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

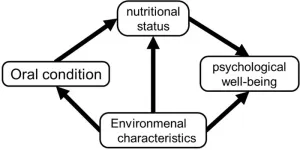

Oral health indirectly influences subjective psychological well-being in older adults

2024-01-30

In humans, oral health influences general health and well-being in many ways. Other than reducing the need for oral rehabilitation later in life, maintaining good oral health reduces the risk of several systemic diseases. Therefore, investing time and effort into improving oral health can be highly beneficial for older adults. However, whether the health benefits of improved oral health extend to psychological domains remains unclear.

Positive psychological well-being is known to positively affect the survival rates of both healthy and unhealthy populations. Thus, to increase life expectancy, it is important to identify the factors associated with ...

Asparagus and orchids are more similar than you think

2024-01-30

What does an asparagus have in common with a vanilla orchid? Not much, if you are just looking at the two plants’ appearances. However, when you look inside - their leaves are more similar than you would think – as revealed by the composition of their cell walls.

By studying plant cell walls – which are to plants what skeletons are to humans – we can reveal the composition of how leaves and stems of plants are actually constructed. This is exactly what a team of University of Copenhagen researchers has done, in a large comprehensive study. In doing so, they have created something truly novel: a large "reference catalogue" ...

DNA particles that mimic viruses hold promise as vaccines

2024-01-30

Using a virus-like delivery particle made from DNA, researchers from MIT and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard have created a vaccine that can induce a strong antibody response against SARS-CoV-2.

The vaccine, which has been tested in mice, consists of a DNA scaffold that carries many copies of a viral antigen. This type of vaccine, known as a particulate vaccine, mimics the structure of a virus. Most previous work on particulate vaccines has relied on protein scaffolds, but the proteins used in those vaccines tend to generate an unnecessary immune response that can distract the immune system from the target.

In the mouse study, the researchers found that the ...

Citizen scientists contribute to motor learning research

2024-01-30

A new research study examined the results from data generated by citizen scientists using a simple web-based motor test. The big data approach provides researchers with a unique way to explore how people correct for motor control errors. The resulting insights may one day pave the way for personalized physical therapy or tailor an athlete’s training routine. The results are available in the January 30th issue of the journal Nature Human Behaviour.

“This exploratory approach does not replace lab based studies, but complements ...

New research shows how pollutants from aerosols and river run-off are changing the marine phosphorus cycle in coastal seas

2024-01-30

New research into the marine phosphorus cycle is deepening our understanding of the impact of human activities on ecosystems in coastal seas.

The research, co-led by the University of East Anglia, in partnership with the Sino-UK Joint Research Centre at the Ocean University of China, looked at the impact of aerosols and river run-off on microalgae in the coastal waters of China.

It identified an ‘Anthropogenic Nitrogen Pump’ which changes the phosphorus cycle and therefore likely coastal biodiversity and associated ecosystem services.

In a balanced ecosystem, microalgae, also known as phytoplankton, provide food for a wide ...

How a mouse’s brain bends time

2024-01-30

Life has a challenging tempo. Sometimes, it moves faster or slower than we’d like. Nevertheless, we adapt. We pick up the rhythm of conversations. We keep pace with the crowd walking a city sidewalk.

“There are many instances where we have to do the same action but at different tempos. So the question is, how does the brain do it," says Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Assistant Professor Arkarup Banerjee.

Now, Banerjee and collaborators have uncovered a new clue that suggests the brain bends our processing of time to suit our ...

Religious people coped better with the Covid-19 pandemic, research suggests

2024-01-30

People of religious faith may have experienced lower levels of unhappiness and stress than secular people during the UK’s Covid-19 lockdowns in 2020 and 2021, according to new University of Cambridge research.

The findings follow a recently published Cambridge-led study suggesting that worsening mental health after experiencing Covid infection – either personally or in those close to you – was also somewhat ameliorated by religious belief. This study looked at the US population during early 2021.

University of Cambridge economists argue ...

IHI launches a new interdisciplinary initiative to revolutionize the way Alzheimer’s disease is detected, diagnosed, prevented, and treated

2024-01-30

Stockholm, January 30, 2024 — Members of the AD-RIDDLE consortium announced today that they will begin a new initiative that aims to bridge the gap between Alzheimer’s research, implementation science, and precision medicine. The AD-RIDDLE programme will offer healthcare professionals a suite of validated solutions for timely detection and diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and dementias, to match individuals with the right interventions at the right time, enabling people to better understand what they can do to reduce risk and prevent cognitive decline.

Alzheimer’s disease represents a major public ...

Goats can tell if you are happy or angry by your voice alone

2024-01-30

HONG KONG (18 Jan 2024) — Goats can tell the difference between a happy-sounding human voice and an angry-sounding one, according to research co-led by Professor Alan McElligott, an expert in animal behaviour and welfare at City University of Hong Kong (CityUHK).

The study reveals that goats may have developed a sensitivity to our vocal cues over their long association with humans, according to the study published in Animal Behaviour.

Long known for their own sonorous vocal skills, goats in the study tended to spend longer gazing towards the source of the sound after a change in the valence of a human voice, i.e., when the playback switched from a happier to ...

Scientists identify how fasting may protect against inflammation

2024-01-30

Cambridge scientists may have discovered a new way in which fasting helps reduce inflammation – a potentially damaging side-effect of the body’s immune system that underlies a number of chronic diseases.

In research published in Cell Reports, the team describes how fasting raises levels of a chemical in the blood known as arachidonic acid, which inhibits inflammation. The researchers say it may also help explain some of the beneficial effects of drugs such as aspirin.

Scientists have known for some time that our diet – particular a high calorie Western diet – can increase our risk of diseases ...