(Press-News.org) AMES, Iowa – At a Biotechnology Council event a few years ago, Nicole Valenzuela’s ears perked up when she heard what a group of researchers in Iowa State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine had in the works: a method for creating a lab-grown, simplified mimic of dog intestines.

“I told them, ‘Oh! I want to do that but with turtles. Is it doable?” said Nicole Valenzuela, professor of ecology, evolution and organismal biology at Iowa State.

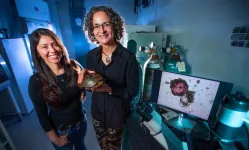

It is indeed doable, new research from a team led by Valenzuela shows. The three-dimensional clusters grown from adult stems cells are called organoids and are designed to assist in research. In a paper published Feb. 22 in Communications Biology, a peer-reviewed journal, Valenzuela and her colleagues describe their creation of organoids that mimic a liver from three species of turtles. It’s the first set of organoids developed for turtles and only the second for any reptile.

Studying turtle genetics with a liver organoid should speed up research to uncover the cause of turtle traits that could potentially have medical applications for humans – the ability of painted turtles to survive weeks without oxygen and withstand extreme cold, for instance.

“Some of their unique adaptations make painted turtles an interesting model for biomedicine. But they remain understudied because it’s difficult work to do. The idea here is to eliminate that bottleneck,” Valenzuela said.

Benefits of organoids

Valenzuela has been researching turtles for more than three decades, drawn to study these animals because of their temperature-dependent sex determination. In many turtles, colder eggs are more likely to produce males, while a warmer nest brings more females.

In studying the genetic causes of traits, biologists eventually need to validate their findings to confirm a gene is functioning as suspected. That requires manipulating those genes, which is a challenge with turtles because they reproduce seasonally and mature slowly, Valenzuela said.

“It’s easy when you’re working with fruit flies or flatworms, but doing transgenic experiments on turtles is pretty much impossible,” she said.

That’s part of why researchers are increasingly developing organoids, she said. The species- and organ-specific mimics expand the range for modern gene editing, allowing scientists to devote more attention to animals that are promising research targets but challenging to study.

“From a single chunk of tissue, you can have an unlimited source of experiment subjects and don’t have to sample animals constantly. Organoids are an important technology for reducing live animal research,” Valenzuela said.

Tweaking the recipe

Valenzuela’s team built their process on the methods used by the research group in the College of Veterinary Medicine, whose work on organoids included a canine intestinal model for testing drug absorption rates. The leads on the canine intestine project – Karin Allenspach and Jon Mochel, now at the University of Georgia – also were part of the turtle organoid project. Recent ISU doctoral graduate Christopher Zdyrski was the first author on the turtle organoid paper.

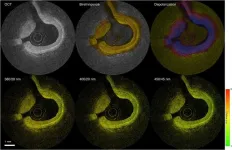

Organoids are made by culturing a tissue sample in a solution that stimulates production of stem cells, the special cells within a body responsible for repair and growth. Given the right fuel, turtle liver stem cells start making turtle liver cells. The microscopic ball of cells is hollow at first but less so as cells accumulate, Valenzuela said. A three-dimensional cluster is better than a flat layer of single cells at mimicking the complexity of actual tissue, even if not fully.

Valenzuela said her team chose to focus first on the liver because it plays a critical role in helping turtles survive extreme cold and oxygen deprivation. The liver produces proteins and enzymes to boost cellular defenses against freezing and provides the small amount of energy a turtle needs for anaerobic metabolism to survive without oxygen, using their shells and bones to manage the resulting lactic acid build-up.

Applying a process designed for dog intestines to a different organ in a different animal took some modification but not necessarily an overhaul, similar to swapping out ingredients in a recipe, she said.

“All of the discovery is in developing those protocols and in characterizing how similar the organoids are to the original liver tissue,” she said.

What’s next

Organoids generated by Valenzuela’s team came from samples collected in Iowa from juvenile spiny softshell and snapping turtles as well as juvenile, adult and embryonic painted turtles. Seeing success across multiple species and developmental stages suggests the techniques could be replicated broadly, she said.

Valenzuela’s group is already at work on creating organoids from turtle gonads, to further investigate the underlying causes of sex determination. They’re also seeking grant funding to study oxygen deprivation and resistance to cold using the novel turtle liver organoids.

But given the lack of genomic tools for studying reptiles – the only other known reptilian organoid is from snake venom glands, the researchers reported in their paper – Valenzuela is optimistic that her team’s work will be used by herpetologists to expand their research.

“That’s the hope, that other scientists adopt these protocols to study other reptiles,” she said.

END

Lab-grown liver organoid to speed up turtle research, making useful traits easier to harness

2024-03-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Patients with Parkinson’s disease who experience freezing of gait have sleep disorders, study shows

2024-03-05

Parkinson’s disease patients who experience freezing of gait (a sudden inability to initiate or continue movement, often resulting in a fall) wake up several times during the night, feel sleepy during the day, and have REM sleep behavior disorder. Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep plays a role in the maintenance of many cognitive processes.

These are key findings of a study supported by FAPESP and conducted by researchers at São Paulo State University (UNESP) in Brazil and Grenoble Alps University (UGA) in France. An article on the study is published in ...

Study finds no safety concerns when the dapivirine vaginal ring is used during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy, according to results presented at CROI 2024

2024-03-05

PITTSBURGH, March 5, 2024 -- Results of the third and final cohort of the DELIVER (MTN-042) Phase IIIb study found no safety concerns with use of the monthly dapivirine vaginal ring beginning during the second trimester of pregnancy and up to the time of delivery, researchers reported today at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI 2024) in Denver. With this latest data, the researchers believe there is now sufficient evidence that the dapivirine ring is safe to use ...

After decades of Arctic sea ice getting faster and more hazardous for transport, models suggest a dramatic reversal is coming, York University study finds

2024-03-05

TORONTO, March 5, 2024 – Will ice floating in the Arctic Ocean move faster or slower over the coming decades? The answer to this question will tell us whether marine transportation can be expected to get more or less hazardous. It might also have important implications for the rate of ice cover loss, which is hugely consequential for Northern Indigenous communities, ecosystems, and the global climate system.

While observational data suggest the trend has been towards faster sea ice speeds, ...

Pioneering work in computational and theoretical neuroscience is awarded the world’s largest brain research prize

2024-03-05

The Lundbeck Foundation has announced the recipients of The Brain Prize 2024, the world’s largest award for outstanding contributions to neuroscience. This year’s award recognizes the pioneering work of three leading neuroscientists – Professor Larry Abbott at Columbia University (USA), Professor Terrence Sejnowski at the Salk Institute (USA), and Professor Haim Sompolinsky at Harvard University (USA) and the Hebrew University (Israel).

Theoretical and computational neuroscience permeates neuroscience today ...

New cardiovascular imaging approach provides a better view of dangerous plaques

2024-03-05

WASHINGTON — Researchers have developed a new catheter-based device that combines two powerful optical techniques to image the dangerous plaques that can build up inside the arteries that supply blood to the heart. By providing new details about plaque, the device could help clinicians and researchers improve treatments for preventing heart attacks and strokes.

Atherosclerosis occurs when fats, cholesterol and other substances accumulate on the artery walls, which can cause these vessels to become thick ...

BU study finds robotic-assisted surgery for gallbladder cancer as effective as traditional surgery

2024-03-05

(Boston)—Each year, approximately 2,000 people die annually of gallbladder cancer (GBC) in the U.S., with only one in five cases diagnosed at an early stage. With GBC rated as the first biliary tract cancer and the 17th most deadly cancer worldwide, pressing attention for proper management of disease must be addressed. For patients diagnosed, surgery is the most promising curative treatment. While there has been increasing adoption of minimally invasive surgical techniques in gastrointestinal malignancies, including utilization of laparoscopic ...

We know the Arctic is warming -- What will changing river flows do to its environment?

2024-03-05

AMHERT, Mass.– Scientists at the University of Massachusetts Amherst recently combined satellite data, field observations and sophisticated numerical modeling to paint a picture of how 22.45 million square kilometers of the Arctic will change over the next 80 years. As expected, the overall region will be warmer and wetter, but the details—up to 25% more runoff, 30% more subsurface runoff and a progressively drier southern Arctic, provides one of the clearest views yet of how the landscape will respond to climate change. The results were published in the journal The Cryosphere.

The Arctic is defined ...

BU researcher examines clinicians’ attitudes towards major changes from the 2020 ACS Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines

2024-03-05

(Boston)—Nearly all cervical cancers are caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV). New evidence has led to dramatic changes in cervical cancer screening recommendations over the past 20 years. In 2020, the American Cancer Society (ACS) released updated guidelines for cervical cancer screening. The main changes to current practices were to initiate screening at age 25 instead of age 21 and to screen using primary HPV testing rather than cytology (PAP test) alone or in combination with HPV testing. Since adoption of guidelines often occurs slowly, understanding clinician attitudes is important ...

The Arctic could become ‘ice-free’ within a decade

2024-03-05

The Arctic could see summer days with practically no sea ice as early as the next couple of years, according to a new study out of the University of Colorado Boulder.

The findings, published March 5 in the journal Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, suggest that the first ice-free day in the Arctic could occur over 10 years earlier than previous projections, which focused on when the region would be ice-free for a month or more. The trend remains consistent under all future emission scenarios.

By ...

Habitual short sleep duration, diet, and development of type 2 diabetes in adults

2024-03-05

About The Study: In this study involving 247,000 UK residents, habitual short sleep duration was associated with increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes. This association persisted even among participants who maintained a healthy diet. To validate these findings, further longitudinal studies are needed, incorporating repeated measures of sleep (including objective assessments) and dietary habits.

Authors: Christian Benedict, Ph.D., of Uppsala University in Uppsala, Sweden, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi: ...