Research reveals endurance exercise training impacts biological molecules

CU faculty member Wendy Kohrt, PhD, describes a national research effort to better understand exercise’s impact on the body using human and animal models

2024-05-21

(Press-News.org) As part of an ongoing national research effort to better understand how physical activity improves health and prevents disease, seven University of Colorado Department of Medicine faculty members contributed to an article recently published in Nature, an international journal of science.

The paper, “Temporal dynamics of the multi-omic response to endurance exercise training,” discusses how eight weeks of endurance exercise training affected male and female young adult rats. The researchers found that all bodily tissues that were tested responded to exercise training — even those not normally associated with movement. This means there were more than 35,000 biological molecules responding and adapting to endurance exercise over time. Researchers also found more widespread differences in molecular responses between male and female rats than they had originally expected.

Traditionally, research has focused on a single bodily tissue or has had a bias toward one sex. This research is unique because it is getting a comprehensive, organism-wide view of the impact of endurance exercise training for both female and male rats.

The research was conducted by the Molecular Transducers of Physical Activity Consortium (MoTrPAC). This program, supported by the National Institutes of Health Common Fund, aims to identify exercise’s impact on the biological molecules of both animals and humans, with the goal of discovering how exercise improves and maintains the health of the body’s tissues and organs.

We asked Wendy Kohrt, PhD, a distinguished professor in the Division of Geriatric Medicine and a leader in the research effort, to discuss the need for this research, the long-term goals of the study, and her takeaways from the recent research paper. Kohrt is the chair of the executive and steering committees of MoTrPAC, as well as the principal investigator of one of the MoTrPAC clinical centers.

The following interview has been edited and condensed.

Q: How would you describe the purpose of your study’s work and the need for this research?

Everybody knows that exercise is good for you, but very few doctors will prescribe exercise. We don’t have the knowledge base to know when we can prescribe exercise to prevent or treat specific health conditions or diseases. That’s because we don’t know the mechanisms by which exercise generates its benefits.

This is the first big leap into developing that underlying evidence base for how exercise works in each of our cells, tissues, and organs. It will fuel the next generation of research to better understand the effectiveness of exercise to prevent or treat disease.

Generating the evidence base to help doctors know when exercise is a reasonable alternative to a medication in hitting these molecular targets is one way I envision this database eventually being used.

Q: Can you provide an overview of the research MoTrPAC has done and is currently conducting?

This paper is on the effects of eight weeks of exercise training. We also studied rats’ responses to just a single bout of exercise, so we are continuing to do deep dives into each piece of the animal studies. We’ve already had several companion papers come out, following the landscape paper.

Our human studies are still happening, with the goal of finishing them next year. We will have somewhere between 1,500 and 1,600 adults and close to 300 adolescents participating. We’re working on two landscape papers from approximately 200 adults enrolled before the COVID pandemic — one will be focused on clinical data and the other will focus on the body’s molecular responses, much like this recently published animal paper. There will be many companion papers that will subsequently come out, as well. This “pilot study” will help guide the analysis of the larger study.

Q: The recently published research paper explains that many tissues in the male and female rats showed sex differences in their exercise training responses. What do you think this means for future research?

We know that women have been under-studied in clinical research, but female animals and cells have often been under-studied in basic and preclinical science as well. I think a lot of my colleagues were surprised by the number, magnitude, and variability of the sex differences between the male and female rats. That is going to be important for any follow-up studies.

The rat has been a pretty good model for how humans respond to exercise in general, but I am cautious because there are some differences in terms of rats and humans with respect to sex differences. For example, in humans, men have higher levels of cardiorespiratory fitness than women. That’s not true in this species of rat.

As excited as I was to see all these sex differences in molecular signaling factors, I’m cautious about the extent to which we’re going to be able to assume these reflect what happens in humans. We need more research to understand whether the sex differences that we see in animals in their blood, muscle, and fat tissues are also reflected in humans.

Q: When looking at the research findings, what were some of your biggest takeaways? Did anything surprise you?

One thing that surprised me was the effect of exercise on the kidney. I knew that exercise is good for people with kidney disease, but looking at this research, you see the number of changes in renal tissue was enormous — and this is one place where there were very pronounced sex differences.

The other result that stood out was brown adipose tissue. Most of our fat is white adipose tissue, but brown adipose tissue got its name because of its color, and it has more mitochondria. For a long time, it was believed that humans lost their brown adipose tissue shortly after birth. However, in the last 15 years, there has been considerably more interest in the fact that humans do seem to maintain some brown adipose tissue into adulthood, although it seems to decline with advancing age and may also decline in women around the time of menopause. Many suspect that this decline in brown adipose tissue is associated with increased propensity for weight gain. And so, looking at this research and seeing that brown adipose tissue signals appear to be mostly male-specific is of great interest to me.

Overall, it's too early to make any leaps of faith regarding what these molecular data are telling us in terms of human physiology, but they are going to help people generate plausible hypotheses about how all these molecular signals might be involved in any health condition or disease that we think might be benefited from regular exercise.

END

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2024-05-21

Amsterdam, May 21, 2024 – The number of people suffering from Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is expected to reach 100 million by 2050, but there is still no effective therapy. Leading researchers from around the world assess how oxidative stress (OS) may trigger AD and consider potential therapeutic targets and neuroprotective drugs to manage the disease in a collection of articles in a special supplement to the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, published by IOS Press.

AD is the most common type of dementia and involves areas of ...

2024-05-21

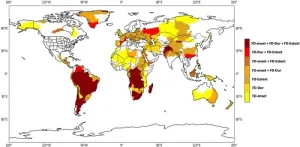

WASHINGTON — Sudden, severe dry spells known as flash droughts are rising in intensity around the world, with a notable exception in mountainous Central Asia, where flash drought extent is shrinking, according to new research. Heat and changes to precipitation patterns caused by a warming climate are driving these trends, the study found.

Flash droughts arrive suddenly, within weeks, hitting communities that are often not prepared and causing lasting impact. They are an emerging concern for water and food security. The new study is the first to apply a systematic, quantitative approach to the global incidence of flash drought, mapping hotspots and ...

2024-05-21

About The Study: Public health authorities in nearly all states and territories surveyed reported the ability to monitor and test persons exposed to highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A(H5N1) virus. However, jurisdictions varied in their capacity to monitor exposed persons, in recommendations for use of antivirals, and in potential use of H5N1 vaccines, if available, among first responders.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Noah Kojima, M.D., email nkojima@cdc.gov.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this ...

2024-05-21

Today, DRI, one of our nation’s leading applied environmental research institutes, together with its Foundation, announced a new global initiative with the first in a series of summits. The event will be held at Encore Las Vegas from August 21-23, 2024.

The AWE+ initiative will promote an Adaptable World Environment of strong, resilient communities in a climate shifting world. AWE+ 2024 - Wildfire Recovery and Resilience: Working Across Silos to Drive Solutions - is a global call-to-action for communities ...

2024-05-21

HOUSTON ― The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Research Highlights showcases the latest breakthroughs in cancer care, research and prevention. These advances are made possible through seamless collaboration between MD Anderson’s world-leading clinicians and scientists, bringing discoveries from the lab to the clinic and back.

Recent developments at MD Anderson offer insights into biomarkers that predict immunotherapy responses, a possible treatment strategy for patients with LKB1-deficient cancers, therapeutic targets to prevent acute myeloid leukemia (AML) progression ...

2024-05-21

Sensors enable us to monitor changes in systems of all kinds.

The materials at the heart of those sensors, of course, ultimately determine their end-use application. Devices made of silicon, for example, enable ultrafast processing in computers and phones, but they aren’t pliable enough for use in physiological monitoring.

They also require a lot of energy to produce.

Lehigh University professor Elsa Reichmanis, Carl Robert Anderson Chair in the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, recently received a grant from the National ...

2024-05-21

Birmingham researchers have shown PEPITEM, a naturally occurring peptide (small protein) holds promise as a new therapeutic for osteoporosis and other disorders that feature bone loss, with distinct advantages over existing drugs.

PEPITEM (Peptide Inhibitor of Trans-Endothelial Migration) was first identified in 2015 by University of Birmingham researchers.

The latest research, published today in Cell Reports Medicine, show for the first time that PEPITEM could be used as a novel and early clinical intervention to reverse the impact of age-related musculoskeletal diseases, with ...

2024-05-21

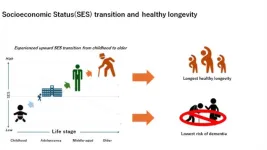

About The Study: This cohort study of Japanese older adults identified that upward and downward socioeconomic status transitions were associated with risk of dementia and the length of dementia-free periods over the lifespan. The results may be useful to understand the association between social mobility and healthy longevity.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Hiroyasu Iso, Ph.D., email iso@pbhel.med.osaka-u.ac.jp.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.12303)

Editor’s Note: Please see ...

2024-05-21

Osaka, Japan – Upward social mobility may ward off dementia, according to a new study. Dementia, a collective term for conditions marked by memory loss and diminished cognitive functioning, strains healthcare systems and devastates quality of life for patients and their families. Research thus far has found correlations between socioeconomic status (SES) – Parent’s asset, education level, income, and work status – and susceptibility to dementia, and SES changes throughout a person’s life, known as social mobility, seem to influence this risk; however, scientific ...

2024-05-21

Scientists discover ‘zoned development’ in dinosaur skin, with zones of reptile-style scales and zones of bird-like skin with feathers

New dinosaur skin fossil found to be composed of silica – the same as glass

Discovery sheds light on evolution from scales to feathers

Palaeontologists at University College Cork (UCC) in Ireland have discovered that some feathered dinosaurs had scaly skin like reptiles today, thus shedding new light on the evolutionary transition from scales to feathers.

The researchers studied a new specimen of the feathered dinosaur Psittacosaurus from the early Cretaceous ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Research reveals endurance exercise training impacts biological molecules

CU faculty member Wendy Kohrt, PhD, describes a national research effort to better understand exercise’s impact on the body using human and animal models