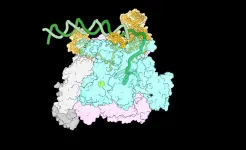

(Press-News.org) Every living cell transcribes DNA into RNA. This process begins when an enzyme called RNA polymerase (RNAP) clamps onto DNA. Within a few hundred milliseconds, the DNA double helix unwinds to form a node known as the transcription bubble, so that one exposed DNA strand can be copied into a complementary RNA strand.

How RNAP accomplishes this feat is largely unknown. A snapshot of RNAP in the act of opening that bubble would provide a wealth of information, but the process happens too quickly for current technology to easily capture visualizations of these structures. Now, a new study in Nature Structural & Molecular Biology describes E. coli RNAP in the act of opening the transcription bubble.

The findings, captured within 500 milliseconds of RNAP mixing with DNA, shed light on fundamental mechanisms of transcription, and answer long-standing questions about the initiation mechanism and the importance of its various steps. “This is the first time anybody has been able to capture transient transcription complexes as they form in real time,” says first author Ruth Saecker, a research specialist in Seth Darst‘s laboratory at Rockefeller. “Understanding this process is crucial, as it is a major regulatory step in gene expression.”

An unprecedented view

Darst was the first to describe the structure of bacterial RNAP, and teasing out its finer points has remained a major focus of his lab. While decades of work have established that RNAP binding to a specific sequence of DNA triggers a series of steps that open the bubble, how RNAP separates the strands and positions one strand in its active site remains hotly debated.

Early work in the field suggested that bubble opening acts as a critical slowdown in the process, dictating how quickly RNAP can move onto RNA synthesis. Later results in the field challenged that view, and multiple theories emerged about the nature of this rate-limiting step. “We knew from other biological techniques that, when RNAP first encounters DNA, it makes a bunch of intermediate complexes that are highly regulated,” says coauthor Andreas Mueller, a postdoctoral fellow in the lab. “But this part of the process can happen in less than a second, and we were unable to capture structures on such a short timescale.”

To better understand these intermediate complexes, the team collaborated with colleagues at the New York Structural Biology Center, who developed a robotic, inkjet-based system that could rapidly prepare biological samples for cryo-electron microscopy analysis. Through this partnership, the team captured complexes forming in the first 100 to 500 milliseconds of RNAP meeting DNA, yielding images of four distinct intermediate complexes in enough detail to enable analysis.

For the first time, a clear picture of the structural changes and intermediates that form during the initial stages of RNA polymerase binding to DNA snapped into focus. “The technology was extremely important to this experiment,” Saecker says. “Without the ability to mix DNA and RNAP quickly and capture an image of it in real-time, these results don’t exist.”

Getting into position

Upon examining these images, the team managed to outline a sequence of events showing how RNAP interacts with the DNA strands as they separate, at previously unseen levels of detail. As the DNA unwinds, RNAP gradually grips one of the DNA strands to prevent the double helix from coming back together. Each new interaction causes RNAP to change shape, enabling more protein-DNA connections to form. This includes pushing out one part of a protein that blocks DNA from entering RNAP’s active site. A stable transcription bubble is thus formed.

The team proposes that the rate-limiting step in transcription may be the positioning of the DNA template strand within the active site of the RNAP enzyme. This step involves overcoming significant energy barriers and rearranging several components. Future research will aim to confirm this new hypothesis and explore other steps in transcription.

“We only looked at the very earliest steps in this study,” Mueller says. “Next, we’re hoping to look at other complexes, later time points, and additional steps in the transcription cycle.”

Beyond resolving conflicting theories about how DNA strands are captured, these results highlight the value of the new method, which can capture molecular events happening within milliseconds in real-time. This technology will enable many more studies of this kind, helping scientists visualize dynamic interactions in biological systems.

“If we want to understand one of the most fundamental processes in life, something that all cells do, we need to understand how its progress and speed are regulated,” says Darst. “Once we know that, we’ll have a much clearer picture of how transcription begins.”

END

Researchers capture never-before-seen view of gene transcription

2024-07-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Do genes-in-pieces code for proteins that fold in pieces?

2024-07-03

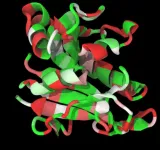

A new study led by Rice University’s Peter Wolynes offers new insights into the evolution of foldable proteins. The research was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Researchers at Rice and the University of Buenos Aires used energy landscape theory to distinguish between foldable and nonfoldable parts of protein sequences. Their study illuminates the ongoing debate about whether the pieces of DNA that code for only part of a protein during their origins can fold on their own.

The researchers focused on the extensive relationship between exons in protein structures and the evolution of protein foldability. They highlighted ...

Can inflammation in early adulthood affect memory, thinking in middle age?

2024-07-03

MINNEAPOLIS – Having higher levels of inflammation in your 20s and 30s may be linked to having memory and thinking problems at middle age, according to a study published in the July 3, 2024, online issue of Neurology®, the medical journal of the American Academy of Neurology. The study looked at levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) in the blood. CRP is produced by the liver and increases when there is inflammation in the body. The study does not prove that having higher levels of this protein causes dementia. It only shows an association.

There are two kinds of inflammation. Acute inflammation happens when the body’s immune response jumps into action to fight off infection or ...

Poor health, stress in 20s takes toll in 40s with lower cognition

2024-07-03

Higher inflammation in young adulthood linked to lower performance in skills testing in midlife.

Young adults who have higher levels of inflammation, which is associated with obesity, physical inactivity, chronic illness, stress and smoking, may experience reduced cognitive function in midlife, a new study out of UC San Francisco has found.

Researchers previously linked higher inflammation in older adults to dementia, but this is one of the first studies to connect inflammation in early adulthood with lower cognitive abilities in midlife.

“We know from long-term studies that brain changes leading to Alzheimer’s ...

Scientists may have found how to diagnose elusive neuro disorder

2024-07-03

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), a mysterious and deadly neurological disorder, usually goes undiagnosed until after a patient dies and an autopsy is performed. But now, UC San Francisco researchers have found a way to identify the condition while patients are still alive.

A study appearing in Neurology on July 3 has found a pattern in the spinal fluid of PSP patients, using a new high-throughput technology that can measure thousands of proteins in a tiny drop of fluid.

Researchers ...

Cracking the code for cerebellar movement disorders

2024-07-03

The cerebellum is a region of the brain that helps us refine our movements and learn new motor skills. Patients and mouse models experience many kinds of abnormal movements when their cerebellum is damaged. They can have uncoordinated and unbalanced movements, called ataxia. They can have atypical positioning of body parts or uncontrolled movements because their muscles are working against each other, called dystonia. Or they can have disruptive shaky movements, called tremors. Understanding how changes in a single brain region ...

Stability indicating RP-HPLC method for the estimation of impurities in esomeprazole gastro-resistant tablets by AQbD approach

2024-07-03

https://www.scienceopen.com/hosted-document?doi=10.15212/bioi-2024-0018

Announcing a new article publication for BIO Integration journal. Esomeprazole (ESO) gastro-resistant tablets (40 mg) are sold under the brand name, Zosa, which effectively manages conditions associated with the overproduction of gastric acid, including peptic ulcer disease and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. This article quantifies impurities in esomeprazole using advanced analytical techniques known as analytical quality by design with high-performance liquid chromatography.

Buffer selection ...

Clinical implications and procedural complications in patients with patent foramen ovale concomitant with atrial septal aneurysm

2024-07-03

https://www.scienceopen.com/hosted-document?doi=10.15212/CVIA.2024.0038

Announcing a new article publication for Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications journal. Atrial septal aneurysm (ASA) is defined as excursion of the atrial septum exceeding 10 mm beyond the atrial septum into the right or left atrium, or a combined total excursion of 15 mm on the right and left sides during the cardiac cycle. According to previous studies, 20–40% of patent foramen ovale (PFO) cases are accompanied by ASAs. ASA is associated with the presence of PFO, left atrial dysfunction, cryptogenic stroke, migraine, and arterial embolism, thus making ...

Cryptocurrency investors are more likely to self-report “Dark Tetrad” personality traits alongside other characteristics

2024-07-03

Owning cryptocurrency may be associated with certain personality and demographic characteristics as well as a reliance on alternative or fringe social media sources, according to a study published July 3, 2024 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Shane Littrell from the University of Toronto, Canada, along with colleagues from the University of Miami, USA.

Anonymous trading and unregulated markets hallmark cryptocurrency’s unique subculture. While some consider the digital currency to be financially unreliable, hundreds of millions of global investors think otherwise.

This study identified various political, psychological, and social characteristics ...

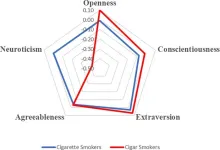

Smoking behavior is linked to personality traits

2024-07-03

Cigarette smokers, cigar smokers, and non-smokers each have distinct personality profiles, according to a study published July 3, 2024 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Dritjon Gruda from Universidade Catolica Portuguesa, Portugal, and Jim McCleskey from Western Governors University, USA.

Tobacco use remains a formidable global public health challenge, responsible for more than 8 million deaths annually, including those attributed to second-hand smoke exposure. Emerging research underscores the critical role of psychological factors, including personality traits, in shaping ...

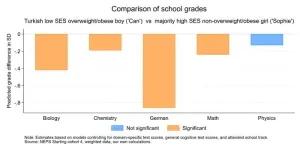

Minority status, social origin, gender, and weight can all count against a German kid’s grades

2024-07-03

A new study done in more than 14,000 ninth graders in Germany has revealed that students experience grading bias based on their gender, body size, ethnicity and parental socio-economic status. These negative biases stack on each other, meaning that students with multiple intersectional identities get significantly lower grades than their peers regardless of their true abilities. Richard Nennstiel and Sandra Gilgen of the University of Bern and University of Zurich in Switzerland present these findings in the open-access journal PLOS ONE on July 3, ...