(Press-News.org) Genetic diversity is essential to the survival of a species. It’s easy enough to maintain if a species reproduces sexually; an egg and a sperm combine genetic material from two creatures into one, forming a genomically robust offspring with two distinct versions of the species’ genome.

Without that combination of different genetic makeups, asexually reproducing species typically suffer from a lack of diversity that can doom them to a limited run on Earth. One such animal should be the clonal raider ant, which produces daughter after genetically identical daughter directly from an unfertilized ovum through parthenogenesis, a method of asexual reproduction in which the offspring inherits two sets of genetically identical chromosomes from its mother.

Over time, the random inheritance of these chromosomes on endless repeat should lead to catastrophic loss of genetic distinctiveness and eventual species collapse. And yet this blind, queenless insect—a native of Bangladesh that is now found in tropical settings around the world—seems to be surviving just fine. How is that possible?

As researchers at Rockefeller University recently discovered, the clonal raider ant doesn’t gamble when it comes to passing along its genes. Instead, it ensures that offspring inherit two distinct versions of its entire genome, largely preserving the genetic diversity present in the ancient founder of each clonal line.

In theory, this shouldn’t work: Chromosomes are thought to randomly shuffle during meiosis, the type of cell division used to produce sperm and egg cells during reproduction in all animals, plants, and fungi. Yet in this animal, the process seems to be anything but random, as they reported in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

“We think we’ve discovered how clonal raider ants are avoiding the loss of genetic diversity that otherwise routinely results from parthenogenesis,” says first author Kip Lacy, a graduate fellow in the Laboratory of Social Evolution and Behavior, led by Daniel Kronauer. “Maybe this diversity enables the survival of the species.”

Asexual conundrums

Parthenogenetic species are rare but found among a variety of life, including reptiles, amphibians, nematodes, fish, and birds. Their chances of long-term existence are slim. “Purely asexual species tend to go extinct pretty fast,” Lacy says.

“Reproducing clonally is kind of a one-way street to deterioration,” adds Kronauer. “Every time there’s a mildly deleterious mutation, you can’t purge it from the genome, which is just going to accumulate more mutations over time.”

The problem starts with two challenges that asexual species must overcome at the cellular level. The first is that they need to make diploid genomes, which contain two sets of chromosomes, to pass on to their offspring.

“But if you’re a clonal raider ant,” Lacy points out, “there is no sperm involved in reproduction, so where are you going to get an extra set of chromosomes?”

The second is that the offspring must have a genetic makeup that is compatible with development and reproduction—which many asexual species, saddled with two sets of genetically identical chromosomes, lack.

Lacy became interested in parthenogenesis during his Master’s degree studies at the University of Georgia while studying the tropical fire ant, some colonies of which asexually produce queens. As he discovered, these ants had almost completely lost their genetic diversity. When he joined Kronauer’s lab in 2019, he sought to find out how the clonal raider ant may avoid such pitfalls.

Mothers and daughters

During meiosis, chromosomes break apart and recombine, resulting in new combinations of gene copies. After these so-called crossover events occur, chromosomes are randomly shuffled through cell divisions.

In parthenogenetic reproduction, a clonal line draws from two identical chromosomal sets, “so you expect to lose a lot of diversity during each cycle,” says Kronauer. It’s akin to watering down the genetic soup.

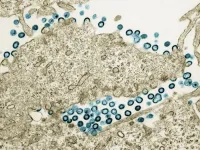

To understand how this may not be true for clonal raider ants, the researchers focused on mother-daughter and sister-sister pairs of ants. To make sure they had true family duos, they tracked transgenic ants that fluoresce red when viewed through a microscope—a breakthrough method of genetic manipulation developed in Kronauer’s lab by researcher Taylor Hart. These pairs were the only animals in their colonies to glow.

Using linked-read genetic sequencing—which allows the reconstruction of whole chromosome sequences—they found that no genetic diversity was lost from mother to daughter. However, the daughter’s genomes showed evidence of crossovers. In all, they documented 144 crossover events, and only one showed a loss of genetic diversity.

“That’s because the chromosomes that have recombined with each other are always inherited together,” Lacy says. “This co-inheritance could explain how this species continues to survive. In clonal raider ants, it’s 800% more likely to occur than would be expected from a random roll of the genetic dice.”

A new tactic

This strategy for retaining genetic diversity has never been documented before, according to Kronauer. Its existence suggests there may be more ways to get around random genetic inheritance than we knew. One well-known deviation from random inheritance, for example, is when “selfish” genes promote their own propagation over other genes, essentially rigging the game in their favor. But this deviation can’t account for clonal raider ant reproduction, which is “unselfish” because no gene has an advantage; all gene copies are co-inherited. Whether this strategy of unselfish inheritance occurs in other animals—including sexually reproducing species—is unknown.

This finding highlights the usefulness of studying species with unusual reproductive biology, Lacy says: “If we hadn’t studied these asexual ants, we might never have learned about this mode of reproduction.”

END

Asexual reproduction usually leads to a lack of genetic diversity. Not for these ants.

2024-07-23

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Mini lungs make major COVID-19 discoveries possible

2024-07-23

Scientists at Sanford Burnham Prebys, University of California San Diego and their international collaborators have reported that more types of lung cells can be infected by SARS-CoV-2 than previously thought, including those without known viral receptors. The research team also reported for the first time that the lung is capable of independently mustering an inflammatory antiviral response without help from the immune system when exposed to SARS-CoV-2.

This work is especially timely, as cases of COVID-19 are on the rise in the scientists’ hometown of San Diego during a summertime spike. Looking beyond the region, more than half of the states in the country have reported “very ...

Exploratory analysis associates HIV drug abacavir with elevated cardiovascular disease risk in large global trial

2024-07-23

WHAT:

Current or previous use of the antiretroviral drug (ARV) abacavir was associated with an elevated risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in people with HIV, according to an exploratory analysis from a large international clinical trial primarily funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). There was no elevated MACE risk for the other antiretroviral drugs included in the analysis. The findings will be presented at the 2024 International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2024) in Munich, Germany.

The Randomized Trial to Prevent Vascular Events in HIV (REPRIEVE) enrolled 7,769 study participants with HIV from 12 countries that found ...

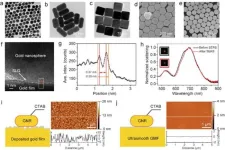

Control of light–matter interactions in two-dimensional materials with nanoparticle-on-mirror structures

2024-07-23

A new publication from Opto-Electronic Sciences; DOI 10.29026/oes.2024.230051 , discusses control of light–matter interactions in two-dimensional materials with nanoparticle-on-mirror structures.

With the rapid development of high bit-rate wireless services driven by mobile internet, AI computing, high-definition videos, virtual reality/augmented reality (VAR) applications, and so on, the demand for wireless data rates has grown explosively in the past decades1, 2. Supporting such fast data rate at tens of Gbit/s pushes the carrier frequency to the THz (0.1-10 THz) ...

Does the onset of daylight saving time lead to an unhealthy lifestyle?

2024-07-23

Researchers from North Carolina State University, University of Manitoba, Bern University of Applied Sciences, University of South Carolina, and California Baptist University published a new Journal of Marketing study that explores whether the onset of daylight saving time leads consumers to engage in unhealthy behaviors.

The study, forthcoming in the Journal of Marketing, is titled “Spring Forward = Fall Back? The Effect of Daylight Saving Time Change on Consumers’ Unhealthy Behavior” and is authored by Ramkumar Janakiraman, Harsha ...

Best Paper awards lack transparency and do not increase equitability

2024-07-23

Research awards are an integral part of the universal “prestige economy” in science, but do they incentivize greater transparency, inclusivity, and openness? This study uses cross-disciplinary data to explore the level of transparency of publicly available award descriptions and assessment criteria, asking whether such awards contribute to or propagate existing reproducibility crises and inequities in science.

#####

In your coverage, please use this URL to provide access to the freely available paper in PLOS Biology: http://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.3002715

Article ...

Brain’s support cells contribute to Alzheimer’s disease by producing toxic peptide

2024-07-23

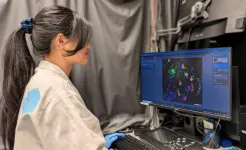

Oligodendrocytes are an important source of amyloid beta (Aβ) and play a key role in promoting neuronal dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), according to a study published July 23, 2024 in the open-access journal PLOS Biology by Rikesh Rajani and Marc Aurel Busche from the UK Dementia Research Institute at University College London, and colleagues.

AD is a devastating neurodegenerative disorder affecting millions of people worldwide. Accumulation of Aβ – peptides consisting of 36 to 43 amino acids – ...

Co-analysis of methylation platforms for signatures of biological aging in the domestic dog

2024-07-23

“In this study, we explore the potential of the three largest, publicly available DNA methylation datasets in dogs to identify signals of biological age.”

BUFFALO, NY- July 23, 2024 – A new research paper was published in Aging (listed by MEDLINE/PubMed as "Aging (Albany NY)" and "Aging-US" by Web of Science) Volume 16, Issue 13, entitled, “Co-analysis of methylation platforms for signatures of biological aging in the domestic dog reveals previously unexplored confounding factors.”

Chronological age reveals the number of years an individual has lived since birth. By contrast, biological age varies between individuals of the same chronological ...

Mass layoffs and data breaches could be connected, according to researchers

2024-07-23

BINGHAMTON, N.Y. -- A research team led by faculty from Binghamton University, State University of New York has been exploring how mass layoffs and data breaches could be connected. Their theory: since layoffs create conditions where disgruntled employees face added stress or job insecurity, they are more likely to engage in risky behaviors that heighten the company’s vulnerability to data breaches.

The research, outlined in a paper titled “The Impacts of Layoffs Announcement on Cybersecurity Breaches,” was presented by Binghamton ...

How does the brain respond to sleep apnea?

2024-07-23

Nearly 40 million adults in the U.S. have sleep apnea, and more than 30 million of them use a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine while sleeping. However, the machines tend to be expensive, clunky and uncomfortable — resulting in many users giving up on using them.

High blood pressure is often linked with sleep apnea because the brain works harder to regulate blood flow and breathing during sleep. A recent study at the University of Missouri offers new insight into the underlying mechanisms within the brain contributing ...

NYU Abu Dhabi researchers discover tumor suppressor protein Par-4 triggers unique cell death pathway in cancerous cells

2024-07-23

Abu Dhabi, July 22, 2024: A team of researchers at NYU Abu Dhabi, led by Professor Sehamuddin Galadari, has discovered that the tumor suppressor protein Prostate apoptosis response-4 (Par-4) can cause a unique type of cell death called ferroptosis in human glioblastoma – the most common and aggressive type of brain tumor – while sparing healthy cells. This new understanding has the potential to inform the development of novel treatments for various hard-to-treat cancers and neurodegenerative diseases.

Ferroptosis is triggered by the iron-mediated production of reactive ...