(Press-News.org) Media

When clams gamble on living with a killer, sometimes their luck may run out, according to a University of Michigan study.

A longstanding question in ecology asks how can so many different species co-occur, or live together, at the same time and at the same place. One influential theory called the competitive exclusion principle suggests that only one species can occupy a particular niche in a biological community at any one time.

But out in the wild, researchers find many instances of different species that appear to occupy the same niches at the same time, living in the same microhabitats and consuming the same food.

U-M ecology and evolutionary biology graduate student Teal Harrison and her adviser Diarmaid Ó Foighil examined one such instance: a highly specialized community of seven marine clam species living in the burrows of their host species, a predatory mantis shrimp.

Six of these seven clam species, called yoyo clams, attach to the shrimp's burrow walls with a long foot used to spring, yoyo-like, away from danger. The seventh of the clam species, a close relative of the yoyo clams, has a distinct within-burrow niche in that it attaches directly to the host mantis shrimp's body and does not yoyo. The researchers wondered how this unusual clam community persists.

"We've got this remarkable situation where all these clam species not only share the same host but most of them have also evolved, or speciated, on that host. How is this possible?" said Ó Foighil, also a curator of mollusks at the U-M Museum of Zoology.

When Harrison conducted field samples of these clam species in mantis shrimp burrows, what she found went against theoretical expectations: all burrows that contained multiple species of clams were composed solely of the burrow wall yoyo clams. And when the host-attached clam species was added to the mix in a laboratory experiment, the mantis shrimp killed all of the burrow-wall clams.

This goes against theoretical expectation, the researchers say. According to the competitive exclusion principle, species that evolve to live in different niches should live together more frequently than species that occupy the same niche. But Harrison's data, published in the journal PeerJ, suggest that the evolution of a new, host-attached niche has paradoxically led to ecological exclusion, not cohabitation, among these commensal clams.

"Teal had two sets of unexpected results. One of them was that the species that should co-occur with the yoyo clams doesn't. And the second unexpected result was that the host can go rogue," Ó Foighil said. "The interesting twist is the only survivor was a clam attached to the mantis shrimp's body. Anything on the burrow wall, it killed. It even went outside the burrow and killed one that had wandered out."

The competitive exclusion principle predicts that the six yoyo clam species (which

share the burrow-wall niche) will co-occupy host burrows less frequently with

each other than with the (niche-differentiated) host-attached clam species. Harrison tested this prediction by field-censusing populations in the Indian River Lagoon, Florida. This involved carefully capturing host mantis shrimp by hand and sampling their burrows for clams using a stainless-steel bait pump.

Harrison then built artificial burrows in the laboratory where she could study, up close, commensal clam behavior with and without a mantis shrimp host. Just two-and-a-half days after setup, almost all of the clams in the mantis shrimp's burrow were dead.

"It was very surreal," Harrison said. "It honestly didn't even dawn on me that they were eaten right away because it was so far from what I was expecting to find. They are commensal organisms, they cohabitate with these mantis shrimp in the wild, and there was no possible way we would know whether this behavior was already happening this way in the wild or not. I just wasn't expecting it."

Harrison was devastated. Ó Foighil was excited.

"Teal was understandably distraught when the experiment 'failed' after all her hard work, but I was excited," Ó Foighil said. "When you get a completely unexpected result in science, it's potentially telling you something brand new and important."

The researchers say that the exclusion mechanism—blocking burrow-wall and host-attached clam co-occurrence—is currently unclear. One reason could be that, during the larval stage, burrow wall clams recruit to different host burrows than the host-attached clams. But it also could be differential survival in burrow assemblages that have both burrow wall and host-attached clams—that is, potentially that mixed population of clams triggers a lethal reaction in the host, Ó Foighil said.

The researchers' next steps are to look into what happened. It could have been an artifact of the setup in the lab, Ó Foighil said. Or it could be telling the researchers that under some conditions, the commensal association of the burrow wall yoyo clams and the predatory host can "break down catastrophically," he said.

"It was pretty cool to have a finding that was contrary to what we were expecting based on evolutionary theory, and it was not only contrary to our theoretical expectations, but it happened in such a dramatic way," Harrison said.

The researchers have proposed two follow-up studies. The first to determine if both types of commensals can recruit as larvae to the same host burrows. The second to test whether the mantis shrimp itself is the culprit: does its predatory behavior change when the host-attached species is added to its burrow?

Study co-authors include Ryutaro Goto of Kyoto University, who initiated this line of work as a postdoctoral researcher in Ó Foighil's lab, and Jingchun Li of the University of Colorado, also a former graduate student in the Ó Foighil lab.

Study: Within-host adaptive speciation of commensal yoyo clams leads to ecological exclusion, not co-existence

END

Living with a killer: How an unlikely mantis shrimp-clam association violates a biological principle

2024-08-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Researchers urge united nations to reject growth-driven framework in favor of lower population and consumption

2024-08-06

In a new peer-reviewed article in The Journal of Population and Sustainability, demographic experts are urging the United Nations to reject the current “‘growth’ paradigm which treats Earth and its nonhuman inhabitants as mere resources” and to take the lead in “contracting the large-scale variables of the human enterprise” in order to “forge a path out of multiple environmental and social crises,” and “reverse our advanced state of ecological overshoot.”

Earth Overshoot Day, the date when humanity’s demand on nature’s resources surpasses Earth’s capacity ...

Future enterovirus outbreaks could be exacerbated by climate change

2024-08-06

Outbreaks of hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD), which causes fever and rash in young children, typically occur in the summer months. Similarly, historic cases of polio were observed in the summer months in the United States. Both diseases are caused by different species of enteroviruses, a large genus of RNA viruses. However, the drivers of the seasonal patterns of these diseases have remained somewhat unclear.

A common set of drivers can explain the timing of outbreaks of both HFMD and polio according a recent study by researchers at Brown University, Princeton University ...

Genetic ‘episignatures’ guide researchers in identifying causes of unsolved epileptic neurological disorders

2024-08-06

(Memphis, Tenn. – August 6, 2024) To effectively treat a disease or disorder, doctors must first know the root cause. Such is the case for developmental and epileptic encephalopathies (DEEs), whose root causes can be hugely complex and heterogeneous. Scientists at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital demonstrated the value of DNA methylation patterns for identifying the root cause of DEEs, showing specific gene methylation and genome-wide methylation “episignatures” ...

Study explores effects of racial discrimination on Black parents and children

2024-08-06

URBANA, Ill. – Black Americans experience racial discrimination on a regular basis, and it is a cause of chronic and pervasive stress. It is known to contribute to elevated risk for poor mental health outcomes, but most research has focused on individuals. A new study from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign looks at the interpersonal effects of discrimination on parents and their adolescent children.

“A person’s experiences with racial discrimination are not just their own but may spill over into the ...

Wayne State University professor receives career achievement award from the Society for Health Psychology

2024-08-06

DETROIT — Mark Lumley, Ph.D., distinguished professor of psychology in Wayne State University’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, was recently awarded the 2024 Nathan W. Perry, Jr. Award for Career Service to Health Psychology from the Society for Health Psychology.

The Society for Health Psychology is a national nonprofit that seeks to improve the lives of individuals and society by promoting health, preventing illness and improving health care through research, practice, education, training and advocacy.

“I’m delighted and greatly honored for this recognition,” ...

Elephants on the move: Mapping connections across African landscapes

2024-08-06

URBANA, Ill. -- Elephant conservation is a major priority in southern Africa, but habitat loss and urbanization mean the far-ranging pachyderms are increasingly restricted to protected areas like game reserves. The risk? Contained populations could become genetically isolated over time, making elephants more vulnerable to disease and environmental change.

A recent study from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and the University of Pretoria in South Africa demonstrates how African conservation managers could create and optimize elephant movement corridors across a seven-country ...

Youth mental health-related emergency room trips declined significantly after Illinois ended COVID-19 lockdown

2024-08-06

Social media’s rise to popularity between 2010 and 2020 has been strongly correlated with the nationwide freefall in youth mental health that characterized the 2010s. Lawmakers have put increasing pressure on the U.S. government to take social media regulation more seriously, with cases about platforms like Facebook, Instagram and X rising to the Supreme Court level.

But despite the ubiquity of social media, scientists at Northwestern Medicine and Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago found that in Illinois, youth emergency room visits and hospitalizations for depression and anxiety decreased ...

How plants become bushy, or not

2024-08-06

or many plants, more branches means more fruit. But what causes a plant to grow branches? New research from the University of California, Davis shows how plants break down the hormone strigolactone, which suppresses branching, to become more “bushy.” Understanding how strigolactone is regulated could have big implications for many crop plants.

The study was published August 1 in Nature Communications.

“Being able to manipulate strigolactone could also have implications beyond plant architecture, including on a plant’s resilience to drought and pathogens,” said senior author Nitzan Shabek, an associate professor in the UC Davis Department of ...

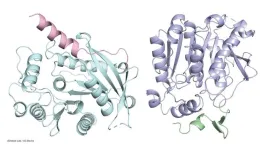

Research spotlight: Identifying potential new protein targets for melanoma therapeutics

2024-08-06

How would you summarize your study for a lay audience?

Some proteins, such as programmed cell death protein 1 (PD1), can stop the immune system from attacking cancer cells and, therefore, support the growth of cancer. Therapies targeting these proteins can be highly effective, but tumors can become resistant.

We applied a method to detect proteins on a single–cell level to uncover human carcinoembryonic antigen cell adhesion molecule 1 (CEACAM1) patterns in melanoma. We found that increased ...

Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation awards $5.2 million to top clinical investigators

2024-08-06

Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation awards $5.2 million to top clinical investigators

The Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation has named six new Damon Runyon Clinical Investigators. The recipients of this prestigious award are outstanding, early-career physician-scientists conducting patient-oriented cancer research at major research centers under the mentorship of the nation's leading scientists and clinicians.

The Clinical Investigator Award program was designed to increase the number of physicians capable of translating scientific discoveries into new treatments for cancer patients. Each Awardee will receive $600,000 over three years, ...