All organisms — from fungi to mammals — have the capacity to evolve and adapt to their environments. But viruses are master shapeshifters with an ability to mutate greater than any other organism. As a result, they can evade treatments or acquire resistance to once-effective antiviral medications.

Working with herpes simplex virus (HSV), a new study led by Harvard Medical School researchers sheds light on one of the ways in which the virus becomes resistant to treatment, a problem that could be particularly challenging among people with compromised immune function, including those receiving immune-suppressive treatment and those born with immune deficiencies.

Using a sophisticated imaging technique called cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM), the researchers found that how parts of a protein responsible for viral replication move into different positions can alter the virus’s susceptibility to medicines.

The findings, published Aug. 27 in Cell, answer long-standing questions about why certain viruses, but not others, are susceptible to antiviral medications and how viruses become impervious to drugs. The results could inform new approaches that impede viruses’ capacity to outpace effective therapies.

Counterintuitive results

Researchers have long known changes that occur on the parts of a virus where antiviral drugs bind to it can render it resistant to therapy. However, the HMS researchers found that, much to their surprise, this was often not the case with HSV.

Instead, the investigators discovered that protein mutations linked to drug resistance often arise far from the drug’s target location. These mutations involve alterations that change the movements of a viral protein, or enzyme, that allows the virus to replicate itself. This raises the possibility that using drugs to block or freeze the conformational changes of these viral proteins could be a successful strategy for overcoming drug resistance.

“Our findings show that we have to think beyond targeting the typical drug-binding sites,” said the study’s senior author, Jonathan Abraham, associate professor of microbiology in the Blavatnik Institute at HMS and infectious disease specialist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. “This really helps us see drug resistance in a new light.”

The new findings propel the understanding of how alterations in the conformation of a viral protein — or changes in how the different parts within that protein move when it carries out its function — fuel drug resistance and may be relevant for understanding drug effectiveness and drug resistance in other viruses, the researchers noted.

HSV, estimated to affect billions of people worldwide, is most commonly known as the cause of cold sores and fever blisters, but it can also lead to serious eye infections, brain inflammation, and liver damage in people with compromised immunity. Additionally, HSV can be transmitted from mother to baby via the birth canal during delivery and cause life-threatening neonatal infections.

Clues on resistance rooted in structure and movement

A virus can’t replicate on its own. To do so, viruses must enter a host cell, where they unleash their replication tools — proteins called polymerases — to make copies of themselves.

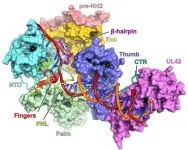

The current study focused on one such protein — a viral DNA polymerase — crucial for HSV’s ability to reproduce and propagate itself. The ability to carry out its function is rooted in the DNA polymerase’s structure, often likened to a hand with three parts: the palm, the thumb, and the fingers, each carrying out critical functions.

Given their role in enabling replication, these polymerases are critical targets of antiviral drugs, which aim to stop the virus from reproducing itself and halt the spread of infection. The HSV polymerase is the target of acyclovir, the leading antiviral drug for treating HSV infection, and of foscarnet, a second-line drug used for drug-resistant infections. Both drugs work by targeting the viral polymerase but do so in different ways.

Scientists have long struggled to fully understand how alterations in the polymerase render the virus impervious to normal doses of antiviral drugs and, more broadly, why acyclovir and foscarnet are not always effective against the altered forms of the HSV polymerase.

“Over the years, the structures of many polymerases from various organisms have been determined, but we still don’t fully understand what makes some polymerases, but not others, susceptible to certain drugs,” Abraham said. “Our study reveals that how the different parts of the polymerases move, known as their conformational dynamics, is a critical component of their relative susceptibility to drugs.”

Proteins, including polymerases, are not rigid, motionless objects. Instead, they are flexible and dynamic.Composed of amino acids, they initially fold into a steady, three‐dimensional shape known as the native conformation — their baseline structure. But as a result of various bonding and dispersing forces, the different parts of proteins can move when they come into contact with other cellular components as well as through external influences, such as changes in pH or temperature. For example, the fingers of a polymerase protein can open and close, as would the fingers of a hand.

Conformational dynamics — the ability of different parts of a protein to move — allow them to efficiently administer many essential functions with a limited number of ingredients. A better understanding of polymerase conformational dynamics is the missing link between structures and functions, including whether a protein responds to a drug and whether it could become resistant to it down the road.

Unraveling the mystery

Many structural studies have captured DNA polymerases in various distinct conformations. However, a detailed understanding of the impact of polymerase conformational dynamics on drug resistance is lacking. To solve the puzzle, the researchers carried out a series of experiments, focusing on two common polymerase conformations — an open one and a closed one — to determine how each affects drug susceptibility.

First, using cryo-EM, they conducted structural analysis to get high-resolution visualizations of the atomic structures of HSV polymerase in multiple conformations, as well as when bound to the antiviral drugs acyclovir and foscarnet. The drug-bound structures revealed how the two drugs selectively bind polymerases that more readily adopt one conformation versus another. One of the drugs, foscarnet, works by trapping the fingers of the DNA polymerase so that they are stuck in a so-called closed configuration.

Further, structural analysis paired with computational simulations suggested that several mutations that are distant from the sites of drug binding confer antiviral resistance by altering the position of the polymerase fingers responsible for closing onto the drug to halt DNA replication.

The finding was an unexpected twist. Up until now, scientists have believed that polymerases closed partially only when they attached to DNA and closed fully only when they added a DNA building block, a deoxynucleotide. It turns out, however, that HSV polymerase can fully close just by being near DNA. This makes it easier for acyclovir and foscarnet to latch on and stop the polymerase from working, thus halting viral replication.

“I’ve worked on HSV polymerase and acyclovir resistance for 45 years. Back then I thought that resistance mutations would help us understand how the polymerase recognizes features of the natural molecules that the drugs mimic,” said study co-author Donald Coen, professor of biological chemistry and molecular pharmacology at HMS. “I’m delighted that this work shows that I was wrong and finally gives us at least one clear reason why HSV polymerase is selectively inhibited by the drug.”

Authorship, funding, disclosures

Additional authors included Sundaresh Shankar, Junhua Pan, Pan Yang, Yuemin Bian, Gábor Oroszlán, Zishuo Yu, Purba Mukherjee, David J. Filman, James M. Hogle, Mrinal Shekhar.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (awards R21 AI141940 and R01 AI19838), with additional funding from a Centers for Integrated Solutions in Infectious Diseases grant.

END