(Press-News.org) Bothnia dystrophy is a form of hereditary blindness, prevalent in the region Västerbotten in Sweden. A new study at Karolinska Institutet published in Nature Communications shows that gene therapy can improve vision in patients with the disease.

Bothnia dystrophy occurs mainly in the region Västerbotten in Sweden, but the disease has also been identified in other parts of the world. The disease leads to progressive visual impairment due to the destruction of the visual cells in the retina. It is caused by an inherited genetic mutation that leads to damage to a particular protein in the eye. There is currently no treatment for the disease.

Researchers at the Karolinska Institute have now investigated whether gene therapy can improve vision in people with the disease. The researchers used a so-called viral vector, a specially designed virus that was genetically modified to contain a functioning RLBP1 gene, the gene that is damaged in Bothnia dystrophy.

The viral vector was injected under the retina through an advanced surgical procedure in 12 people with the disease. The aim is that after treatment, the viral vector will be taken up by the cells of the retina, where it can produce normal protein.

The preliminary results of the study show that the visual function of 11 of the subjects improved significantly.

“The results are important because hereditary blindness is the most common cause of blindness in younger and able-bodied people, and there is no treatment for the vast majority of those affected,” says Helder André, one of the researchers behind the study, who works at the Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet.

After the procedure, the researchers followed the study subjects for a year to study the safety and effect of the drug on visual function. In eleven of the twelve study subjects, night vision, among other things, improved significantly, and in several participants, this led to improved self-perceived quality of life. No serious side effects linked to the drug were noted in the study.

“Our study gives hope that this large group of patients can have their vision restored in the future. The results also support the idea that gene therapy can work for hereditary diseases in general,” says Anders Kvanta, professor of ophthalmology at the same department and the person who led the study.

The next step is a larger study comparing the effect on treated study subjects with a control group that has not been treated.

The study was conducted at St. Erik Eye Hospital in Stockholm. The sponsor of the study was Novartis and the study team included Novartis employees. None of the team at St. Erik's Eye Hospital has ties to Novartis or any other conflict of interest.

Publikation: “Interim safety and efficacy of gene therapy for RLBP1-associated retinal dystrophy: a phase 1/2 trial”, Anders Kvanta, Nalini Rangaswamy, Karen Holopigian, Christine Watters, Nicki Jennings, Melissa S. H. Liew, Chad Bigelow, Cynthia Grosskreutz, Marie Burstedt, Abinaya Venkataraman, Sofie Westman, Asbjörg Geirsdottir, Kalliopi Stasi, and Helder André, Nature Communications, online September 10, 2024, doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-51575-4

END

Gene therapy effective in hereditary blindness

2024-09-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Report: Conscientiousness, not willpower, is a reliable predictor of success

2024-09-10

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — According to two psychologists, the field of psychological science has a problem with the concept of self-control. It has named self-control both a “trait” — a key facet of personality involving attributes like conscientiousness, grit and the ability to tolerate delayed gratification — and a “state,” a fleeting condition that can best be described as willpower. These two concepts are at odds with one another and are often confused, the authors report.

“Self-control is a cherished quality. People who have lots of it are celebrated and seen as morally righteous,” wrote University of Toronto psychology professor Michael Inzlicht ...

Advancing prison safety

2024-09-10

The lead article in the current issue of The Criminologist, written by Nancy Rodriguez, University of California Irvine professor of criminology, law and society, shines a light on the lack of prison violence metrics that could help advance safety.

“For the 800,000 persons currently confined and the 200,000 state and federal correctional officers who work within U.S. prisons, the threat of violence is a routine feature of daily life,” she writes. “Accounts from incarcerated persons and staff detail the ever-present threats ...

Towards a better understanding of epigenetics and dynamic gene silencing and reactivation

2024-09-10

Ikoma, Japan – One of the most fascinating discoveries in biology is that cells have mechanisms for dynamically regulating genetic expression. This ability to promote or restrict the transcription of specific genes without altering the DNA sequences themselves is essential to all forms of life, from single-cell organisms to the most complex plants and animal species.

While our understanding of these so-called epigenetic mechanisms is far from complete, remarkable progress has been made in this field with the understanding of the role of the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2). PRC2 is a protein that, in many plants, binds to specific DNA sequences called polycomb ...

Artificial muscles propel a robotic leg to walk and jump

2024-09-09

Inventors and researchers have been developing robots for almost 70 years. To date, all the machines they have built – whether for factories or elsewhere – have had one thing in common: they are powered by motors, a technology that is already 200 years old. Even walking robots feature arms and legs that are powered by motors, not by muscles as in humans and animals. This in part suggests why they lack the mobility and adaptability of living creatures.

A new muscle-powered robotic leg is not only more energy efficient than a conventional one, it can also perform high jumps and fast movements as well as detect and react to obstacles – ...

Researchers develop reaction-induced molybdenum carbides for efficient carbon dioxide conversion

2024-09-09

Molybdenum (Mo) carbides, known for their unique electronic and structural properties, are considered promising alternatives to noble metal catalysts in heterogeneous catalysis. However, traditional methods for preparing Mo carbides suffer from complex processes, stringent synthesis conditions, challenging crystal regulation, and high energy consumption. Additionally, Mo carbides are susceptible to oxidation and deactivation, which poses a significant barrier to their widespread application.

In a study published in Nature Chemistry, a research group led by Prof. SUN Jian from the Dalian Institute ...

Researchers identify factor that drives prostate cancer-causing genes

2024-09-09

For more information, contact:

Nicole Fawcett, nfawcett@umich.edu

EMBARGOED for release at 5 a.m. ET Sept. 9, 2024

Researchers identify factor that drives prostate cancer-causing genes

Factor previously known to play a role in advanced cancer is fundamental in early stages of cancer development

ANN ARBOR, Michigan — Researchers at the University of Michigan Health Rogel Cancer Center have uncovered a key reason why a typically normal protein goes awry and fuels ...

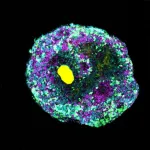

New molecular engineering technique allows for complex organoids

2024-09-09

A new molecular engineering technique can precisely influence the development of organoids. Microbeads made of specifically folded DNA are used to release growth factors or other signal molecules inside the tissue structures. This gives rise to considerably more complex organoids that imitate the respective tissues much better and have a more realistic cell mix than before. An interdisciplinary research team from the Cluster of Excellence “3D Matter Made to Order” with researchers based at the Centre for Organismal Studies and the Center ...

How the brain's inner chamber governs our state of consciousness

2024-09-09

In hospital operating rooms and intensive care units, propofol is a drug of choice, widely used to sedate patients for their comfort or render them fully unconscious for invasive procedures.

Propofol works quickly and is tolerated well by most patients when administered by an anesthesiologist. But what is happening inside the brain when patients are put under and what does this reveal about consciousness itself?

Investigators at U-M who are studying the nature of consciousness have successfully used the drug to identify the intricate brain geometry behind the unconscious state, offering an unprecedented ...

Can coping with a cancer diagnosis contribute to psychological and cardiovascular problems in family members?

2024-09-09

New research suggests that a family member’s cancer diagnosis may increase first-degree relatives’ and spouses’ risks of developing psychological and cardiovascular illnesses. The findings are published by Wiley online in CANCER, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Cancer Society.

Having a family member diagnosed with cancer can be a stressful and traumatic experience for the entire family. Because stress influences not only mental health but also cardiovascular health, investigators explored whether a cancer diagnosis contributes ...

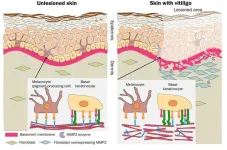

Loss of skin’s pigment-producing cells could be related to basement membrane disruption

2024-09-09

Skin pigmentation disorders affect people across the world. One of them, vitiligo, is said to have a worldwide incidence of 1-2%. What causes the loss of pigmentation in vitiligo has long been unclear, but an Osaka Metropolitan University-led team has uncovered clues to the mechanism behind the disorder.

In findings published in The Journal of Pathology, Graduate School of Medicine Specially Appointed Associate Professor Lingli Yang, the corresponding author, and researchers including Specially Appointed Professor Ichiro ...