(Press-News.org) Crohn’s disease — an autoimmune disorder — is characterized by chronic inflammation of the digestive tract, resulting in a slew of debilitating gastrointestinal symptoms that vary from patient to patient. Complications of the disease can destroy the gut lining, requiring repeated surgeries. The poorly understood condition, which currently has no cure and few treatment options, often strikes young people, causing significant ill-health throughout their lifetime. One barrier to making progress in developing treatments has been the lack of preclinical animal models that accurately replicate this complex disease. Another is the extreme heterogeneity among patients in the clinic, making it difficult for clinicians to tailor therapies.

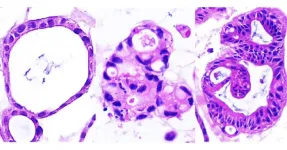

Previous studies of Crohn’s disease have derived organoids from pluripotent stem cells reprogrammed to become gut cells. Now, by studying organoids derived from adult stem cells in the gut tissue of Crohn’s disease patients — which more accurately replicated the traits of the disease — University of California San Diego researchers have discovered that the condition consists of two distinct molecular subtypes.

The findings, published in Cell Reports Medicine on September 26, 2024, could lay the foundation for improved diagnostics and the development of personalized treatment options based on which subtype a patient’s disease falls into.

The researchers sampled gut tissue from 53 Crohn’s disease patients during routine colonoscopies at the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at UC San Diego Health. The patients came from diverse backgrounds and presented with a variety of clinical symptoms. Scientists at the UC San Diego HUMANOIDTM Center of Research Excellence at UC San Diego School of Medicine, led by its director and the first author of the study, Courtney Tindle, created a “biobank” of patient-derived organoid cultures.

Organoids are tiny, lab-grown replicas of organs or tissues that closely mimic the behavior of their real-life counterparts. They are especially useful in medical research when animal models do not adequately represent the disease.

Previous studies of Crohn’s disease have derived organoids from pluripotent stem cells reprogrammed to become gut cells. However, developing the organoids from adult stem cells in gut tissue more accurately replicates the traits of the disease, according to senior author Pradipta Ghosh, M.D., professor of cellular and molecular medicine and executive director of the HUMANOIDTM Center.

“The pluripotent stem cells — whether derived from blood or skin cells, carry the genetic traits of the patient, but have no way to know the inflamed environment inside the patient’s gut,” said Ghosh. In contrast, the adult stem cells retain an epigenetic memory of the gut environment imprinted on the genetic background — including a history of bacterial colonization, inflammation, and altered oxygen and pH. “We show here that adult stem cell-derived organoids accurately mimic the inflamed gut, but the pluripotent cells fail, which reminds me of what Maya Angelou once said: ‘I have great respect for the past. If you don't know where you've come from, you don't know where you're going,’” she added.

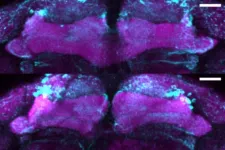

Upon analysis, the researchers were surprised to discover that no matter how many clinically diverse patients they recruited, the organoids consistently fell into one of just two discrete molecular subtypes — each exhibiting unique patterns of genetic mutation, gene expression, and cellular phenotypes.

The two subtypes are:

Immune-deficient infectious-Crohn’s disease (IDICD), characterized by difficulty clearing pathogens, and an insufficient cytokine response by the immune system. These patients tend to form fistulas with pus discharge.

Stress and senescence-induced fibrostenotic-Crohn’s disease (S2FCD), characterized by cellular aging and stress. These patients tend to develop fibrosis — or scarring — of gut epithelial tissue, which may form strictures.

Ghosh believes the discovery of these two distinct molecular subtypes will lead to a shift in the traditional understanding of Crohn’s disease. Instead of classifying patients based on a large array of clinical symptoms, categorizing them by one of the two molecular subtypes could open the door to more personalized and effective management strategies.

“Currently, because of a lack of understanding of these fundamentally different subtypes, they are all being given the same treatment — a cookie-cutter therapy,” said Ghosh. “This combination of anti-inflammatory drugs helps a fraction of the patients, but only temporarily.”

The study revealed that patients with immune-deficient infectious-Crohn’s disease might be better served by therapies that clear their bacterial infections instead.

In contrast, for those with the stress and senescence-induced fibrostenotic-Crohn’s disease subtype, Ghosh says drugs that target or reverse cellular aging — cell-based and stem cell-based therapies that rejuvenate the gut epithelium — might be more effective at treating their disease.

Testing different drugs on patient-derived organoids will help identify which drugs are most effective for each molecular subtype.

She adds that work is underway to genotype the two subtypes in order to develop a simple test that can quickly identify which subtype a patient falls into.

“It’s my hope that when the genetics are completed, Crohn's disease will be viewed as two molecular subtypes that should be treated in two completely different ways.”

Ghosh says future treatments for Crohn’s disease — which affects more than 500,000 Americans — could one day include personalized cell therapies, including gene editing and RNA-based treatments.

“Traditionally, we have been treating this disease with anti-inflammatory drugs, an approach that can be likened to putting out fires. With this study — the first of many based on the ongoing work and the efforts that are going to translate this to the clinic — we hope to target the arsonist who is responsible for the fire in the first place.”

Ghosh says the logistics and infrastructure of HUMANOIDTM and the Institute for Network Medicine uniquely enables bold disease modeling efforts within a collaborative framework that extends from the laboratory bench to the clinic and the cloud. The team partnered with gastroenterologists William Sandborn, M.D. and Brigid S. Boland, M.D. at the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Center at UC San Diego Health, who advised them on disease modeling, and with data scientists who determined how closely the model matched the disease.

Co-authors on the study include: Ayden G. Fonseca, Sahar Taheri, Gajanan D. Katkar, Jasper Lee, Priti Maity, Ibrahim M. Sayed, Stella-Rita Ibeawuchi, Eleadah Vidales, Rama F. Pranadinata, Mackenzie Fuller, Dominik L. Stec, Mahitha Shree Anandachar, Kevin Perry, Helen N. Le, Jason Ear, Debashis Sahoo, and Soumita Das, all at UC San Diego.

The study was funded, in part, by the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, the National Institutes of Health (Grants AI141630, DK107585, R56 AG069689, DiaComp Pilot and Feasibility award, R01-GM138385), and Padres Pedal the Cause/C3 Collaborative Translational Cancer Research Award (San Diego NCI Cancer Centers Council [C3] #PTC2017).

# # #

END

Organoids derived from gut stem cells reveal two distinct molecular subtypes of crohn’s disease

Discovery could pave the way for personalized therapeutics to treat the chronic inflammatory bowel disease

2024-09-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Rates of sudden unexpected infant death changed during the COVID-19 pandemic

2024-09-26

HERSHEY, Pa. — The risk of sudden unexpected infant death (SUID) and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) increased during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic period, especially in 2021, according to a new study led by researchers at the Penn State College of Medicine. Monthly increases in SUID in 2021 coincided with a resurgence of seasonal respiratory viruses, particularly respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), suggesting that the shift in SUID rates may be associated with altered infectious disease transmission.

They ...

Genetic rescue for rare red foxes?

2024-09-26

A rescue effort can take many forms – a life raft, a firehose, an airlift. For animals whose populations are in decline from inbreeding, genetics itself can be a lifesaver.

Genomic research led by the University of California, Davis, reveals clues about montane red foxes’ distant past that may prove critical to their future survival. The study, published in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution, examines the potential for genetic rescue to help restore populations of these mountain-dwelling red foxes. The research is especially relevant for the estimated ...

Extreme heat impacts daily routines and travel patterns, study finds

2024-09-26

A groundbreaking new study conducted by a team of researchers from Arizona State University, University of Washington and the University of Texas at Austin reveals that extreme heat significantly alters how people go about their daily lives, influencing everything from time spent at home to transportation choices. The study, titled "Understanding How Extreme Heat Impacts Human Activity-Mobility and Time Use Patterns," was recently published in Transportation Research Part D and underscores the urgent need for policy action ...

ReadCube expands literature management with new AI Assistant and comprehensive search

2024-09-26

Digital Science announces ReadCube Pro, an AI-powered expansion of ReadCube, offering researchers new tools to simplify and accelerate literature management and literature monitoring workflows.

The new AI Assistant and Literature Monitoring in ReadCube – an award-winning leader in literature management and full-text document delivery – transform the way research teams access, organize, review and monitor scholarly literature by providing them with enhanced search capabilities while helping to significantly reduce time spent ...

New mutation linked to early-onset Parkinsonism

2024-09-26

Leuven, 26 September 2024 – A team of scientists led by Prof. Patrik Verstreken (VIB-KU Leuven) has identified a new genetic mutation that may cause a form of early-onset Parkinsonism. The mutation, located in a gene called SGIP1, was discovered in an Arab family with a history of Parkinson's symptoms that began at a young age. The study reveals that this mutation affects how brain cells communicate, providing new insights into the disease's development and potential treatment strategies.

A genetic clue to Parkinsonism

Parkinsonism is a group of neurological disorders that share similar symptoms, including motor dysfunction ...

Bacteria involved in gum disease linked to increased risk of head and neck cancer

2024-09-26

More than a dozen bacterial species among the hundreds that live in people’s mouths have been linked to a collective 50% increased chance of developing head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), a new study shows. Some of these microbes had previously been shown to contribute to periodontal disease, serious gum infections that can eat away at the jawbone and the soft tissues that surround teeth.

Experts have long observed that those with poor oral health are statistically more vulnerable than those with healthier ...

These fish use legs to taste the seafloor

2024-09-26

Sea robins are unusual animals with the body of a fish, wings of a bird, and walking legs of a crab. Now, researchers show that the legs of the sea robin aren’t just used for walking. In fact, they are bona fide sensory organs used to find buried prey while digging. This work appears in two studies published in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on September 26.

“This is a fish that grew legs using the same genes that contribute to the development of our limbs and then repurposed these legs to find ...

This fish has legs

2024-09-26

Sea robins are ocean fish particularly suited to their bottom-dwelling lifestyle: Six leg-like appendages make them so adept at scurrying, digging, and finding prey that other fish tend to hang out with them and pilfer their spoils.

A chance encounter in 2019 with these strange, legged fish at Cape Cod’s Marine Biological Laboratory was enough to inspire Corey Allard to want to study them.

“We saw they had some sea robins in a tank, and they showed them to us, because they know we like weird animals,” said Allard, a ...

Climate change: Heat, drought, and fire risk increasing in South America

2024-09-26

The number of days per year that are simultaneously extremely hot, dry, and have a high fire risk have as much as tripled since 1970 in some parts of South America. The results are published in a study in Communications Earth & Environment.

South America is warming at a similar rate to the global average. However, some regions of the subcontinent are more at risk of the co-occurrence of multiple climate extremes. These compound extremes can have amplified impacts on ecosystems, economy, and human health.

Raúl Cordero and colleagues calculated the number of days per year that each approximately 30 by 30 km grid ...

Rates of sudden unexpected infant death before and during the pandemic

2024-09-26

About The Study: This cross-sectional study found increased rates of both sudden unexpected infant death (SUID) and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) during the COVID-19 pandemic, with a significant shift in epidemiology from the pre-pandemic period noted in June to December 2021. These findings support the hypothesis that off-season resurgences in endemic infectious pathogens may be associated with SUID rates, with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) rates in the U.S. closely approximating this shift. Further investigation into the role ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Cognitive speed training linked to lower dementia incidence up to 20 years later

Businesses can either lead transformative change or risk extinction: IPBES

Opening a new window on the brainstem, AI algorithm enables tracking of its vital white matter pathways

Dr. Paul Donlin-Asp of the University of Edinburgh to dissect the molecular functions and regulation of local SYNGAP1 protein synthesis with support from CURE SYNGAP1 (fka SynGAP Research Fund)

Seeing the whole from a part: Revealing hidden turbulent structures from limited observations and equations

Unveiling polymeric interactions critical for future drug nanocarriers

New resource supports trauma survivors, health professionals

Evidence of a subsurface lava tube on Venus

New trial aims to transform how we track our daily diet

People are more helpful when in poor environments

How big can a planet be? With very large gas giants, it can be hard to tell

New method measures energy dissipation in the smallest devices

More than 1,000 institutions worldwide now partner with MDPI on open access

Chronic alcohol use reshapes gene expression in key human brain regions linked to relapse vulnerability and neural damage

Have associations between historical redlining and breast cancer survival changed over time?

Brief, intensive exercise helps patients with panic disorder more than standard care

How to “green” operating rooms: new guideline advises reduce, reuse, recycle, and rethink

What makes healthy boundaries – and how to implement them – according to a psychotherapist

UK’s growing synthetic opioid problem: Nitazene deaths could be underestimated by a third

How rice plants tell head from toe during early growth

Scientists design solar-responsive biochar that accelerates environmental cleanup

Construction of a localized immune niche via supramolecular hydrogel vaccine to elicit durable and enhanced immunity against infectious diseases

Deep learning-based discovery of tetrahydrocarbazoles as broad-spectrum antitumor agents and click-activated strategy for targeted cancer therapy

DHL-11, a novel prieurianin-type limonoid isolated from Munronia henryi, targeting IMPDH2 to inhibit triple-negative breast cancer

Discovery of SARS-CoV-2 PLpro inhibitors and RIPK1 inhibitors with synergistic antiviral efficacy in a mouse COVID-19 model

Neg-entropy is the true drug target for chronic diseases

Oxygen-boosted dual-section microneedle patch for enhanced drug penetration and improved photodynamic and anti-inflammatory therapy in psoriasis

Early TB treatment reduced deaths from sepsis among people with HIV

Palmitoylation of Tfr1 enhances platelet ferroptosis and liver injury in heat stroke

Structure-guided design of picomolar-level macrocyclic TRPC5 channel inhibitors with antidepressant activity

[Press-News.org] Organoids derived from gut stem cells reveal two distinct molecular subtypes of crohn’s diseaseDiscovery could pave the way for personalized therapeutics to treat the chronic inflammatory bowel disease