(Press-News.org) A study published in Nature by researchers at Baylor College of Medicine changes the way we understand memory. Until now, memories have been explained by the activity of brain cells called neurons that respond to learning events and control memory recall. The Baylor team expanded this theory by showing that non-neuronal cell types in the brain called astrocytes – star-shaped cells – also store memories and work in concert with groups of neurons called engrams to regulate storage and retrieval of memories.

“The prevailing idea is that the formation and recall of memories only involves neuronal engrams that are activated by certain experiences, and hold and retrieve a memory,” said corresponding author Dr. Benjamin Deneen, professor and Dr. Russell J. and Marian K. Blattner Chair in the Department of Neurosurgery, director of the Center for Cancer Neuroscience, a member of the Dan L Duncan Comprehensive Cancer Center at Baylor and a principal investigator at the Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute.

“Our lab has a long history of studying astrocytes and their interactions with neurons. We have found that these cells interact closely with each other, both physically and functionally, and that this is essential for proper brain function. However, the role of astrocytes in storage and retrieval of memories has not been investigated before,” Deneen said.

Astrocytes trigger memory recall

The researchers began by developing a completely new set of laboratory tools to identify and study the activity of astrocytes associated with memory brain circuits.

A typical experiment consisted of, first, conditioning mice to feel fear and ‘freeze’ after exposure to a certain situation. When mice were placed back in the same situation after some time, they would freeze because they remembered. If the same mice were placed in a different situation, they would not freeze because it’s not the original context in which they were conditioned to feel fear.

“Working with these mice and with our new lab tools, we were able to show that astrocytes do play a role in memory recall,” said co-first author Dr. Wookbong Kwon, a postdoctoral associate in the Deneen lab.

The researchers show that during learning events, such as fear conditioning, a subset of astrocytes in the brain expresses the c-Fos gene. Astrocytes expressing c-Fos subsequently regulate circuit function in that brain region.

“The c-Fos-expressing astrocytes are physically close with engram neurons,” said co-first author Dr. Michael R. Williamson, a postdoctoral associate in the Deneen lab. “Furthermore, we found that engram neurons and the physically associated astrocyte ensemble also are functionally connected. Activating the astrocyte ensemble specifically stimulates synaptic activity or communication in the corresponding neuron engram. This astrocyte-neuron communication flows both ways; astrocytes and neurons depend on each other.”

When mice were in a situation not associated with fear, they did not freeze. “However, when the astrocyte ensemble in these mice in the non-fearful environment was activated, the animals froze, showing that astrocyte activation stimulates memory recall,” Kwon said.

To better understand what mediates the activity of astrocyte ensembles in memory recall, the researchers investigated the gene NFIA. “Our lab has previously shown that astrocytic NFIA can regulate memory circuits, but whether it acts in ensembles of astrocytes to orchestrate memory storage and recall was unknown,” Williamson said.

The team found that astrocytes activated by learning events have elevated levels of the NFIA protein, and preventing NFIA production in these astrocytes suppresses memory recall. Importantly, this suppression is memory specific.

“When we deleted the NFIA gene in astrocytes that were active during a learning event, the animals were not able to recall the specific memory associated with the learning event, but they could recall other memories,” Kwon said.

“These findings speak to the nature of the role of astrocytes in memory,” Deneen said. “Ensembles of learning-associated astrocytes are specific to that learning event. The astrocyte ensembles regulating the recall of the fearful experience are different from those involved in recalling a different learning experience, and the ensemble of neurons is different as well.”

The current study illuminates a more complete picture of the players that are involved and the activities that take place in the brain during memory formation and recall. In addition, the study provides a new perspective when studying human conditions associated with memory loss, like Alzheimer’s disease, as well as conditions in which memories occur repeatedly and are difficult to suppress, like post-traumatic stress disorder.

Junsung Woo, Yeunjung Ko, Ehson Maleki, Kwanha Yu, Sanjana Murali and Debosmita Sardar also contributed to this work. They are all affiliated with Baylor College of Medicine.

This work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health grants (R35-NS132230, R21-MH134002 and R01-AG071687), grant AHA-23POST1019413 and a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea (RS- 2024-00405396). Further support was provided by the David and Eula Wintermann Foundation, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health award P50HD103555.

###

END

Brain stars hold our memories

2024-11-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Imaging nuclear shapes by smashing them to smithereens

2024-11-06

UPTON, N.Y. — Scientists have demonstrated a new way to use high-energy particle smashups at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) — a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science user facility for nuclear physics research at DOE’s Brookhaven National Laboratory — to reveal subtle details about the shapes of atomic nuclei. The method, described in a paper just published in Nature, is complementary to lower energy techniques for determining nuclear structure. It will add depth to scientists’ understanding of the nuclei that make up the ...

AI-driven mobile robots team up to tackle chemical synthesis

2024-11-06

Researchers at the University of Liverpool have developed AI-driven mobile robots that can carry out chemical synthesis research with axtraordinairy efficiency.

In a study publishing in the journal Nature, researchers show how mobile robots that use AI logic to make decisions were able to perform exploratory chemistry research tasks to the same level as humans, but much faster.

The 1.75-meter-tall mobile robots were designed by the Liverpool team to tackle three primary problems in exploratory chemistry: performing the reactions, ...

New haptic patch transmits complexity of touch to the skin

2024-11-06

A Northwestern University-led team of engineers has developed a new type of wearable device that stimulates skin to deliver various complex sensations.

The thin, flexible device gently adheres to the skin, providing more realistic and immersive sensory experiences. Although the new device obviously lends itself to gaming and virtual reality (VR), the researchers also envision applications in healthcare. For example, the device could help people with visual impairments “feel” their surroundings or give feedback to people with prosthetic limbs.

The ...

Safety of simultaneous vs sequential mRNA COVID-19 and inactivated influenza vaccines

2024-11-06

About The Study: In this randomized clinical trial assessing simultaneous vs sequential administration of mRNA COVID-19 and inactivated influenza vaccines, reactogenicity was comparable in both groups. These findings support the option of simultaneous administration of these vaccines.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Emmanuel B. Walter, MD, MPH, email chip.walter@duke.edu.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.43166)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other ...

Long-term risk of autoimmune and autoinflammatory connective tissue disorders following COVID-19

2024-11-06

About The Study: This retrospective cohort study with an extended follow-up period found associations between COVID-19 and the long-term risk of various autoimmune and autoinflammatory connective tissue disorders. Long-term monitoring and care of patients is crucial after COVID-19, considering demographic factors, disease severity, and vaccination status, to mitigate these risks.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Solam Lee, MD, PhD, email solam@yonsei.ac.kr.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website ...

Mount Sinai researchers have uncovered the mechanism in the brain that constantly refreshes memory

2024-11-06

Mount Sinai researchers have discovered for the first time a neural mechanism for memory integration that stretches across both time and personal experience. These findings, reported in Nature, demonstrate how memories stored in neural ensembles in the brain are constantly being updated and reorganized with salient information, and represent an important step in deciphering how our memories stay current with the most recently available information. This discovery could have important implications for better understanding adaptive memory processes ...

Breakthrough in energy-efficient avalanche-based amorphization could revolutionize data storage

2024-11-06

The atoms of amorphous solids like glass have no ordered structure; they arrange themselves randomly, like scattered grains of sand on a beach. Normally, making materials amorphous — a process known as amorphization — requires considerable amounts of energy. The most common technique is the melt-quench process, which involves heating a material until it liquifies, then rapidly cooling it so the atoms don’t have time to order themselves in a crystal lattice.

Now, researchers ...

Scientists discover how specific E. coli bacteria drive colon cancer

2024-11-06

Ghent, 7 November 2024 – Scientists have uncovered how certain E. coli bacteria in the gut promote colon cancer by binding to intestinal cells and releasing a DNA-damaging toxin. The study, published in Nature, sheds light on a new approach to potentially reduce cancer risk. The study was performed by the teams of Prof. Lars Vereecke (VIB-UGent Center for Inflammation Research) and Prof. Han Remaut (VIB-VUB Center for Structural Biology).

Bacteria and colon cancer

Colon cancer ranks as the third most prevalent and deadliest type of cancer. Alarmingly, its incidence is rising, particularly ...

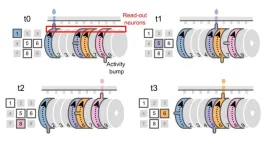

Brain acts like music box playing different behaviours

2024-11-06

Neuroscientists have discovered brain cells that form multiple coordinate systems to tell us “where we are” in a sequence of behaviours. These cells can play out different sequences of actions, just like a music box can be configured to play different sequences of tones. The findings help us understand the algorithms used by the brain to flexibly generate complex behaviours, such as planning and reasoning, and might be useful in understanding how such processes go wrong in psychiatric ...

Study reveals how cancer immunotherapy may cause heart inflammation in some patients

2024-11-06

Some patients being treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors, a type of cancer immunotherapy, develop a dangerous form of heart inflammation called myocarditis. Researchers led by physicians and scientists at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), a founding member of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system, have now uncovered the immune basis of this inflammation. The team identified changes in specific types of immune and stromal cells in the heart that underlie myocarditis and pinpointed factors in the blood that may indicate ...