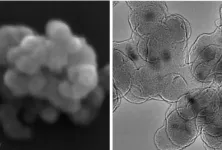

The complex, a type of “protein chaperone” known as TRiC, helps fold thousands of human proteins: It was later found that about 10% of all our proteins pass through its barrel structure.

All animals have several different kinds of protein chaperones, each with its own job of helping fold proteins in the cell. TRiC binds to newborn proteins and shapes these strings of amino acids into the correct 3D structures, allowing them to carry out their important functions in the cell.

Frydman, the Donald Kennedy Chair in the School of Humanities and Sciences and a professor of biology and genetics, met Ingo Kurth, MD, a pediatrician at the RWTH Aachen University, during a recent sabbatical in Germany, who presented her with an interesting conundrum. Three decades after Frydman’s discovery and many more insights into TRiC’s mechanism later, the pediatrician had found a mutation in one of TRiC’s components in a child with intellectual disability, seizures and brain malformations.

Could the TRiC mutation be responsible for the child’s symptoms? Although dysfunctions in the complex are linked to cancer and Alzheimer’s disease, germline mutations — mutations present in all cells in an organism — in TRiC had never been implicated in a developmental disease. Because proteins must be folded correctly to function correctly and because TRiC is involved in shaping so many proteins, scientists assumed any mutation that altered TRiC’s ability to fold proteins would be lethal.

Frydman and her laboratory team set up a collaboration with the RWTH Aachen University researchers to find out more. Along with collaborators from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri, the team explored how this patient’s mutation, which is in a gene known as CCT3, affects TRiC function in roundworms, baker’s yeast and zebrafish. Meanwhile, the pediatricians combed through a genetic database of patients with intellectual disabilities and neurodevelopmental defects similar to those of the original patient. They found 21 more cases of patients with alike symptoms, albeit ranging in severity, with mutations in 7 of the 8 components of TRiC. The Frydman lab showed that all the additional 21 mutations impair TRiC function, causally linking TRiC defects to the brain disorders.

A new class of disease The researchers dubbed this new class of neurological diseases “TRiCopathies” and describe their findings in an article published Oct. 31 in Science. The team has since found an additional patient with mutations in the eighth TRiC subunit.

“This opens a whole new way of thinking about the role of chaperones in brain development,” said Frydman, who is one of the senior authors on the study.

All the patients the researchers identified have one healthy copy of the TRiC complex gene in addition to the mutated version. That squares with the chaperone’s importance — two mutated copies of any of these genes would likely be lethal. Although some of the patients also have muscular deficiencies, it’s interesting that the primary effect of these mutations appears to be neurological, Frydman said. That could point to an outsized role for this chaperone in brain development.

Over the years, her lab has developed methods to study the complex in yeast cells as well as isolated in test tubes. Research scientist Piere Rodriguez-Aliaga, PhD, co-first author on the study, made mutations in the yeast versions of TRiC genes that corresponded to the 22 disease-linked human mutations. He found that some of these mutations led to death of the cells but some did not, indicating that different mutations have different effects depending on the location of these mutations within the TRiC complex, which may explain the diversity of symptoms seen in patients.

Other researchers in the collaboration made similar mutations in roundworms and zebrafish to study how the mutations affected multicellular animals and, in the case of the zebrafish, brain development.

In all three organisms, the researchers found that having only the mutated version CCT3, the TRiC gene, was lethal. In worms and zebrafish, which, like us, have two copies of all their genes, animals with one mutated copy and one healthy copy survived, but the mutated version caused developmental problems. Zebrafish with one mutated CCT3 showed defects in brain development similar to those seen in the human patients, and worms with the mutated gene had problems with movement.

Although it’s not clear which misfolded protein or proteins may be causing the neurological symptoms, the researchers suspect that structural proteins known as actin and tubulin are involved. These proteins are important for cells’ movement and internal stability and are known to be folded by TRiC. Worms carrying TRiC mutations had tiny aggregates of actin not present in healthy animals, a phenomenon that often happens with misfolded proteins. Organelles required for energy called mitochondria, which are key to neuronal function, were also affected.

Frydman and Rodriguez-Aliaga plan to study the mechanism of the disease-linked mutations in more detail by exploring how they affect TRiC’s ability to fold proteins, using methods they’ve established in their lab to study protein folding. They also want to use patient-derived cells they can grow into neurons or brain organoids in the lab to see how the mutations affect human brain cells.

“This work is a nice example of basic science connecting with medicine,” Rodriguez-Aliaga said. “The study would not have been possible without all the years of biochemistry and biophysics done in TRiC since 1992.”

See the paper for other institutions involved in the study as well as funding for the research.

# # #

About Stanford Medicine

Stanford Medicine is an integrated academic health system comprising the Stanford School of Medicine and adult and pediatric health care delivery systems. Together, they harness the full potential of biomedicine through collaborative research, education and clinical care for patients. For more information, please visit med.stanford.edu.

END