(Press-News.org) Researchers have quantified for the first time the global emissions of a sulfur gas produced by marine life, revealing it cools the climate more than previously thought, especially over the Southern Ocean.

The study, published in the journal Science Advances, shows that the oceans not only capture and redistribute the sun's heat, but produce gases that make particles with immediate climatic effects, for example through the brightening of clouds that reflect this heat.

It broadens the climatic impact of marine sulfur because it adds a new compound, methanethiol, that had previously gone unnoticed. Researchers only detected the gas recently, because it used to be notoriously hard to measure and earlier work focussed on warmer oceans, whereas the polar oceans are the emission hotspots.

The research was led by a team of scientists from the Institute of Marine Sciences (ICM-CSIC) and the Blas Cabrera Institute of Physical Chemistry (IQF-CSIC) in Spain. They included Dr Charel Wohl, previously at ICM-CSIC and now at the University of East Anglia (UEA) in the UK.

Their findings represent a major advance on one of the most groundbreaking theories proposed 40 years ago about the role of the ocean in regulating the Earth's climate.

This suggested that microscopic plankton living on the surface of the seas produce sulfur in the form of a gas, dimethyl sulphide, that once in the atmosphere, oxidizes and forms small particles called aerosols.

Aerosols reflect part of the solar radiation back into space and therefore reduce the heat retained by the Earth. Their cooling effect is magnified when they become involved in making clouds, with an effect opposite to, but of the same magnitude as, that of the well-known warming greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide or methane.

The researchers argue that this new work improves our understanding of how the climate of the planet is regulated by adding a previously overlooked component and illustrates the crucial importance of sulfur aerosols. They also highlight the magnitude of the impact of human activity on the climate and that the planet will continue to warm if no action is taken.

Dr Wohl, of UEA’s Centre for Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences and one of the lead authors, said: “This is the climatic element with the greatest cooling capacity, but also the least understood. We knew methanethiol was coming out of the ocean, but we had no idea about how much and where. We also did not know it had such an impact on climate.

“Climate models have greatly overestimated the solar radiation actually reaching the Southern Ocean, largely because they are not capable of correctly simulating clouds. The work done here partially closes the longstanding knowledge gap between models and observations.”

With this discovery, scientists can now represent the climate more accurately in models that are used to make predictions of +1.5 ºC or +2 ºC warming, a huge contribution to policy making.

“Until now we thought that the oceans emitted sulfur into the atmosphere only in the form of dimethyl sulphide, a residue of plankton that is mainly responsible for the evocative smell of shellfish,” said Dr Martí Galí, a researcher at the ICM-CSIC and another of the main study authors.

Dr Wohl added: “Today, thanks to the evolution of measurement techniques, we know that plankton also emit methanethiol, and we have found a way to quantify, on a global scale, where, when and in what quantity this emission occurs.

“Knowing the emissions of this compound will help us to more accurately represent clouds over the Southern Ocean and calculate more realistically their cooling effect.”

The researchers gathered all the available measurements of methanethiol in seawater, added those they had made in the Southern Ocean and the Mediterranean coast, and statistically related them to seawater temperature, obtained from satellites.

This allowed them to conclude that, annually and on a global average, methanethiol increases known marine sulfur emissions by 25%.

“It may not seem like much, but methanethiol is more efficient at oxidising and forming aerosols than dimethyl sulfide and, therefore, its climate impact is magnified,” said co-lead Dr Julián Villamayor, a researcher at IQF-CSIC.

The team also incorporated the marine emissions of methanethiol into a state-of-the-art climate model to assess their effects on the planet's radiation balance.

It showed the impacts are much more visible in the Southern Hemisphere, where there is more ocean and less human activity, and therefore the presence of sulfur from the burning of fossil fuels is lower.

The work was supported by funding from organisations including the European Research Council and Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation.

‘Marine emissions of methanethiol increase aerosol cooling in the Southern Ocean’, Charel Wohl, Julián Villamayor and Martí Galí et al, is published in Science Advances on November 27.

END

Oceans emit sulfur and cool the climate more than previously thought

2024-11-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

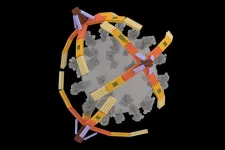

Nanorobot hand made of DNA grabs viruses for diagnostics and blocks cell entry

2024-11-27

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — A tiny, four-fingered “hand” folded from a single piece of DNA can pick up the virus that causes COVID-19 for highly sensitive rapid detection and can even block viral particles from entering cells to infect them, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign researchers report. Dubbed the NanoGripper, the nanorobotic hand also could be programmed to interact with other viruses or to recognize cell surface markers for targeted drug delivery, such as for cancer treatment.

Led by Xing Wang, a professor of bioengineering and of chemistry at the ...

Rare, mysterious brain malformations in children linked to protein misfolding, study finds

2024-11-27

In 1992, Judith Frydman, PhD, discovered a molecular complex with an essential purpose in all of our cells: folding proteins correctly.

The complex, a type of “protein chaperone” known as TRiC, helps fold thousands of human proteins: It was later found that about 10% of all our proteins pass through its barrel structure.

All animals have several different kinds of protein chaperones, each with its own job of helping fold proteins in the cell. TRiC binds to newborn proteins and shapes these strings of amino acids into the correct 3D structures, ...

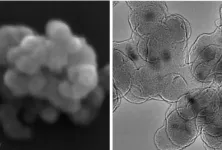

Newly designed nanomaterial shows promise as antimicrobial agent

2024-11-27

HOUSTON – (Nov. 27, 2024) – Newly developed halide perovskite nanocrystals (HPNCs) show potential as antimicrobial agents that are stable, effective and easy to produce. After almost three years, Rice University scientist Yifan Zhu and colleagues have developed a new HPNC that is effective at killing bacteria in a biofluid under visible light without experiencing light- and moisture-driven degradation common in HPNCs.

A new method using two layers of silicon dioxide that Zhu and colleagues developed over years of work was used in experiments with lead-based and bismuth-based HPNCs to test their antimicrobial efficacy and stability in water. ...

Scientists glue two proteins together, driving cancer cells to self-destruct

2024-11-27

Our bodies divest themselves of 60 billion cells every day through a natural process of cell culling and turnover called apoptosis.

These cells — mainly blood and gut cells — are all replaced with new ones, but the way our bodies rid themselves of material could have profound implications for cancer therapies in a new approach developed by Stanford Medicine researchers.

They aim to use this natural method of cell death to trick cancer cells into disposing of themselves. Their method accomplishes this by artificially bringing together two proteins in such a way that the new compound switches on a set of cell death genes, ultimately driving tumor cells to turn on themselves. ...

Intervention improves the healthcare response to domestic violence in low- and middle-income countries

2024-11-27

Culturally appropriate women-centred interventions can help healthcare systems respond to domestic violence, research has found. HERA (Healthcare Responding to Violence and Abuse) has been co-developing and evaluating a domestic violence and abuse healthcare intervention in low- and middle-income countries for the past five years. This National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Global Research Group will report their findings, and publish a PolicyBristol report, at a conference in London today ...

State-wide center for quantum science: Karlsruhe Institute of Technology joins IQST as a new partner

2024-11-27

The mission of IQST is to further our understanding of nature and develop innovative technologies based on quantum science by leveraging synergies between the natural sciences, engineering, and life sciences. "Many KIT scientists already successfully support IQST with their expertise as Fellows. All the more I am pleased that the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology is now joining our interdisciplinary centre as an institution," says IQST Director Prof. Stefanie Barz. "This will strengthen networking within the academic quantum community in Baden-Württemberg," emphasizes ...

Cellular traffic congestion in chronic diseases suggests new therapeutic targets

2024-11-27

***Embargoed until November 27 at 11 AM EST***

Chronic diseases like type 2 diabetes and inflammatory disorders have a huge impact on humanity. They are a leading cause of disease burden and deaths around the globe, are physically and economically taxing, and the number of people with such diseases is growing.

Treating chronic disease has proven difficult because there is not one simple cause, like a single gene mutation, that a treatment could target. At least, that’s how it has appeared to scientists. However, research from Whitehead Institute Member Richard Young and colleagues, published in the journal ...

Cervical cancer mortality among US women younger than age 25

2024-11-27

About The Study: This study found a steep decline in cervical cancer mortality among U.S. women younger than 25 years between 2016 and 2021. This cohort of women is the first to be widely protected against cervical cancer by human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines. The findings from this study in the context of other published research suggest that HPV vaccination affected the sequential decline in HPV infection prevalence, cervical cancer incidence, and cervical cancer mortality.

Corresponding ...

Fossil dung reveals clues to dinosaur success story

2024-11-27

In an international collaboration, researchers at Uppsala University have been able to identify undigested food remains, plants and prey in the fossilised faeces of dinosaurs. These analyses of hundreds of samples provide clues about the role dinosaurs played in the ecosystem around 200 million years ago. The findings have been published in the journal Nature.

“Piecing together ‘who ate whom’ in the past is true detective work,” says Martin Qvarnström, researcher at the Department of Organismal Biology and lead author of the study. “Being able to examine what animals ate and how they interacted with their environment helps us understand what enabled ...

New research points way to more reliable brain studies

2024-11-27

Brain-wide association studies, which use magnetic resonance imaging to identify relationships between brain structure or function and human behavior or health, have faced criticism for producing results that often cannot be replicated by other researchers.

A new study published in Nature demonstrates that careful attention to study design can substantially improve the reliability of this type of research. For the study, Kaidi Kang, a biostatistics PhD student, Simon Vandekar, PhD, associate professor of Biostatistics, and colleagues analyzed data from more than 77,000 brain scans across 63 studies.

The ...