(Press-News.org) A research group led by Johannes Müller at the Institute of Prehistoric and Protohistoric Archaeology, at Kiel University, Germany, have shed light on the lives of people who lived over 5,600 years ago near Kosenivka, Ukraine. Published on December 11, 2024, in the open-access journal PLOS ONE, the researchers present the first detailed bioarchaeological analyses of human diets from this area and provide estimations on the causes of death of the individuals found at this site.

The people associated with the Neolithic Cucuteni-Trypilla culture lived across Eastern Europe from approximately 5500 to 2750 BCE. With up to 15,000 inhabitants, some of their mega-sites are among the earliest and largest city-like settlements in prehistoric Europe. Despite the vast number of artefacts the Trypillia left behind, archeologists have found very few human remains. Due to this absence, many facets of the lives of this ancient people are still undiscovered.

The researchers studied a settlement site near Kosenivka, Ukraine. Comprised of several houses, this site is unique for the presence of human remains. The 50 human bone fragments recovered among the remains of a house stem from at least seven individuals—children, adults, males and a female, perhaps once inhabitants of the house. The remains of four of the individuals were also heavily burnt. The researchers were keen to explore potential causes for these burns, such as an accidental fire, or a rare form of burial rite.

The burnt bone fragments were largely found in the center of the house, and previous studies surmised the inhabitants of this site died in a house fire. Scrutinizing the pieces of bone under a microscope, the researchers concluded that the burning probably occurred quickly after death. In the case of an accidental fire, the researchers propose that some individuals could have died of carbon monoxide poisoning, even if they fled the house.

According to radiocarbon dating, one of the individuals died ca. 100 years later. The death of this person cannot be connected to the fire, but is otherwise unknown. Two other individuals with unhealed cranial injuries raise the question of whether violence could have played a role as well. A review of Trypillian human bone finds showed the researchers that less than 1% of the dead were cremated, and even more rarely buried within a house.

While bones can help archeologists speculate how ancient people died, these remains can also help us understand how they lived. By analyzing the carbon and nitrogen present in the bones—as well as in grains and the remains of animals found at the site—the researchers determined meat made up less than 10% of the inhabitants’ diets. This is in line with teeth found at the site, which have wear marks that indicate chewing on grains and other plant fibers. That Trypillia diets consisted mostly of plants supports theories that cattle in these cultures were primarily used for manuring the fields and milk rather than meat production.

Katharina Fuchs, first author of the study, adds: “Skeletal remains are real biological archives. Although researching the Trypillia societies and their living conditions in the oldest city-like communities in Eastern Europe will remain challenging, our ‘Kosenvika case’ clearly shows that even small fragments of bone are of great help. By combining new osteological, isotopic, archaeobotanical and archaeological information, we provide an exceptional insight into the lives—and perhaps also the deaths—of these people.”

#####

In your coverage please use this URL to provide access to the freely available article in PLOS ONE: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0289769

Author Countries: Germany, Ukraine

Funding: This research has been conducted in the scope of the CRC 1266 ‘Scales of transformation’ at Kiel University, funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG – Projektnummer 290391021 – SFB 1266). Awarded to KF, WK, JM. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

END

New study reveals unique insights into the life and death of Stone Age individuals from modern-day Ukraine

2024-12-11

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Feeling itchy? Study suggests novel way to treat inflammatory skin conditions

2024-12-11

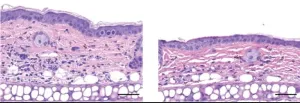

A new approach to treat rosacea and other inflammatory skin conditions could be on the horizon, according to a University of Pittsburgh study published today in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers found that a compound called SYM2081 inhibited inflammation-driving mast cells in mouse models and human skin samples, paving the way for new topical treatments to prevent itching, hives and other symptoms of skin conditions driven by mast cells.

“I’m really excited about the clinical possibilities of this research,” said senior author Daniel Kaplan, M.D., Ph.D., professor ...

Caltech creates minuscule robots for targeted drug delivery

2024-12-11

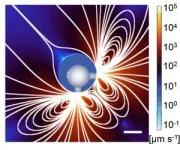

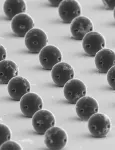

In the future, delivering therapeutic drugs exactly where they are needed within the body could be the task of miniature robots. Not little metal humanoid or even bio-mimicking robots; think instead of tiny bubble-like spheres.

Such robots would have a long and challenging list of requirements. For example, they would need to survive in bodily fluids, such as stomach acids, and be controllable, so they could be directed precisely to targeted sites. They also must release their medical cargo only when they reach their target, and then be absorbable by the body without causing harm.

Now, ...

Noninvasive imaging method can penetrate deeper into living tissue

2024-12-11

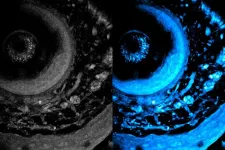

Metabolic imaging is a noninvasive method that enables clinicians and scientists to study living cells using laser light, which can help them assess disease progression and treatment responses.

But light scatters when it shines into biological tissue, limiting how deep it can penetrate and hampering the resolution of captured images.

Now, MIT researchers have developed a new technique that more than doubles the usual depth limit of metabolic imaging. Their method also boosts imaging speeds, yielding richer and more detailed images.

This new technique does not require tissue to be ...

Researchers discover zip code that allows proteins to hitch a ride around the body

2024-12-11

Researchers at The Ottawa Hospital and the University of Ottawa have discovered an 18-digit code that allows proteins to attach themselves to exosomes - tiny pinched-off pieces of cells that travel around the body and deliver biochemical signals. The discovery, published in Science Advances, has major implications for the burgeoning field of exosome therapy, which seeks to harness exosomes to deliver drugs for various diseases.

“Proteins are the body’s own home-made drugs, but they don’t necessarily travel well around the body,” said Dr. Michael Rudnicki, senior ...

The distinct nerve wiring of human memory

2024-12-11

The black box of the human brain is starting to open. Although animal models are instrumental in shaping our understanding of the mammalian brain, scarce human data is uncovering important specificities. In a paper published in Cell, a team led by the Jonas group at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA) and neurosurgeons from the Medical University of Vienna shed light on the human hippocampal CA3 region, central for memory storage.

Many of us have relished those stolen moments with a grandparent by the fireplace, our hearts racing to the intrigues of their stories from good old times, recounted with vivid imagery ...

Researchers discover new third class of magnetism that could transform digital devices

2024-12-11

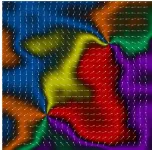

A new class of magnetism called altermagnetism has been imaged for the first time in a new study. The findings could lead to the development of new magnetic memory devices with the potential to increase operation speeds of up to a thousand times.

Altermagnetism is a distinct form of magnetic order where the tiny constituent magnetic building blocks align antiparallel to their neighbours but the structure hosting each one is rotated compared to its neighbours.

Scientists from the University of Nottingham’s School of Physics and Astonomy have shown that this new third class ...

Personalized blood count could lead to early intervention for common diseases

2024-12-11

A complete blood count (CBC) screening is a routine exam requested by most physicians for healthy adults. This clinical test is a valuable tool for assessing a patient’s overall health from one blood sample. Currently, the results of CBC tests are analyzed using a one-size-fits-all reference interval, but a new study led by researchers from Mass General Brigham suggests that this approach can lead to overlooked deviations in health. In a retrospective analysis, researchers show that these reference intervals, or setpoints, are unique to each patient. The study revealed that one healthy ...

Innovative tissue engineering: Boston University's ESCAPE method explained

2024-12-11

When it comes to the human body, form and function work together. The shape and structure of our hands enable us to hold and manipulate things. Tiny air sacs in our lungs called alveoli allow for air exchange and help us breath in and out. And tree-like blood vessels branch throughout our body, delivering oxygen from our head to our toes. The organization of these natural structures holds the key to our health and the way we function. Better understanding and replicating their designs could help us unlock biological insights for more effective drug-testing, and the development of new therapeutics and organ replacements. Yet, biologically engineering tissue ...

Global healthspan-lifespan gaps among 183 WHO member states

2024-12-11

About The Study: This study identifies growing healthspan (years lived in good health)-lifespan gaps around the globe, threatening healthy longevity across worldwide populations. Women globally exhibited a larger healthspan-lifespan gap than men.

Corresponding Author: To contact the corresponding author, Andre Terzic, MD, PhD, email terzic.andre@mayo.edu.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.50241)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article ...

Stanford scientists transform ubiquitous skin bacterium into a topical vaccine

2024-12-11

Imagine a world in which a vaccine is a cream you rub onto your skin instead of a needle a health care worker pushes into your one of your muscles. Even better, it’s entirely pain-free and not followed by fever, swelling, redness or a sore arm. No standing in a long line to get it. Plus, it’s cheap.

Thanks to Stanford University researchers’ domestication of a bacterial species that hangs out on the skin of close to everyone on Earth, that vision could become a reality.

“We all hate needles — everybody does,” said Michael Fischbach, PhD, the Liu (Liao) Family Professor and a professor of bioengineering. “I haven’t found a single person ...