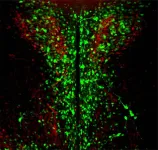

(Press-News.org) PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Scientists discovered years ago that the hypothalamus — which helps to manage body temperature, hunger, sex drive, sleep and more — includes neurons that express the protein opsin 3 (OPN3). Far less clear, however, was what this light-sensing protein does so deep inside the brain.

A study published in PNAS suggests that OPN3 plays an important role in regulating food consumption.

“Our results uncover a mechanism by which the nonvisual opsin receptor OPN3 modulates food intake via the melanocortin 4 receptor MC4R, which is crucial for regulating energy balance and feeding behavior,” said Elena Oancea, a professor of medical science who is affiliated with the Carney Institute for Brain Science at Brown University. “This finding is interesting because loss-of-function mutations in MC4R are a known genetic cause of obesity in humans.”

The study was led by Hala Haddad, who conducted the research while a Ph.D. student and then postdoctoral research associate at Brown, with senior authors Oancea and Richard Lang, director of the Visual Systems Group at Cincinnati Children’s.

The research team reported that OPN3 functions together with MC4R and the Kir7.1 potassium channel to regulate certain cell signals as well as neuronal firing in a key area that controls energy balance. Notably, when mice were engineered to lack OPN3 in this part of the hypothalamus, they ate significantly less and were less active than control mice.

“We're very excited to have, for the first time, a cellular mechanism of what OPN3 is doing in the brain,” Oancea said.

Opsin 3 has been the focus of research in Oancea’s lab for almost a decade, and the team has discovered that it is present in melanocytes, where it functions in pigmentation, and has developed a mouse model to identify the specific brain regions where this protein is expressed. Researchers in Lang’s lab have also been studying OPN3 in fat tissue and in the brain, primarily using mouse genetics tools. The two research teams started collaborating around 2020.

While their findings add an important insight into the function of OPN3, the researchers said more study is necessary to address whether the mechanism also performs in similar ways in the human brain.

“While we identified the mechanism and function of OPN3 in this region of the hypothalamus, how this receptor works in other areas of the brain remains elusive,” Oancea said. “There must be a common paradigm for OPN3 function in different areas, and we're still looking for that.”

Moreover, “the current analysis does not resolve the question of whether OPN3 can function as a light sensor in the mouse brain,” Lang said. “That remains to be addressed in future studies.”

The regulation of eating behavior and body weight is extremely complex, Oancea said.

“Figuring out how to address these complex issues requires a broader understanding of the cellular processes involved,” she said.

This study was supported by the Brown University Imaging Facility and Microscopy Core, and the Transgenic Animal and Genome Editing Core at Cincinnati Children’s. Funding for the research came from the National Institutes of Health (R01AR076241, R01EY027077, R01EY032029, R01EY032752, R01EY032566 and R01EY034456) and the National Science Foundation, among other sources.

END

Researchers discover how opsin 3, a light-sensitive brain protein, regulates food consumption in mice

Researchers at Brown University and Cincinnati Children’s found that suppressing opsin 3 in the brain of mice makes them eat less, raising new questions about the mechanisms involved in regulating human metabolism.

2025-02-14

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New blood test could improve Alzheimer’s Disease diagnosis, research finds

2025-02-14

New blood test could improve Alzheimer’s Disease diagnosis, research finds

Up to half of all people living with Alzheimer’s Disease in Ireland remain undiagnosed. Now, a new blood test may have the potential to transform patient care, allowing for better diagnosis, earlier interventions and more targeted treatments.

Researchers at Trinity College Dublin, the Tallaght Institute of Memory and Cognition and St James’s Hospital, Dublin are exploring the ability of a new blood test, plasma p-tau217, to detect Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). This test could potentially replace the current diagnostic method, a lumbar puncture/spinal tap (which ...

Outstanding Cal Poly public health faculty member and global health advocate among first Faculty Excellence Award honorees

2025-02-14

Cal Poly Assistant Professor Joni Roberts has been chosen, with two additional university faculty members, as the first Cal Poly Faculty Excellence Award honorees.

The inaugural Faculty Excellence Award — an honor recognizing outstanding contributions in teaching, research and service — is administered by the Office of the Provost and funded by generous donor contributions. The award reflects Cal Poly’s commitment to academic excellence and its Learn by Doing philosophy.

The ...

Trees might need our help to survive climate change, CSU study finds

2025-02-14

A new Colorado State University study of the interior U.S. West has found that tree ranges are generally contracting in response to climate change but not expanding into cooler, wetter climates – suggesting that forests are not regenerating fast enough to keep pace with climate change, wildfire, insects and disease.

As the climate becomes too warm for trees in certain places, tree ranges have been expected to shift toward more ideal conditions. The study analyzed national forest inventory data for more than 25,000 plots in ...

Terabytes of data in a millimeter crystal

2025-02-14

From punch card-operated looms in the 1800s to modern cellphones, if an object has an “on” and an “off” state, it can be used to store information.

In a computer laptop, the binary ones and zeroes are transistors either running at low or high voltage. On a compact disc, the one is a spot where a tiny indented “pit” turns to a flat “land” or vice versa, while a zero is when there’s no change.

Historically, the size of the object making the “ones” and “zeroes” has put a limit on the size of the storage device. But now, University of Chicago Pritzker School of Molecular ...

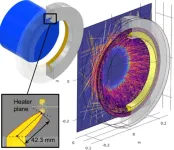

New technology enhances gravitational-wave detection

2025-02-14

RIVERSIDE, Calif. -- In a paper published earlier this month in Physical Review Letters, a team of physicists led by Jonathan Richardson of the University of California, Riverside, showcases how new optical technology can extend the detection range of gravitational-wave observatories such as the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, or LIGO, and pave the way for future observatories.

Since 2015, observatories like LIGO have opened a new window on the universe. Plans for future upgrades to the 4-kilometer LIGO detectors and the construction of a next-generation 40-kilometer observatory, Cosmic Explorer, aim to push the gravitational-wave ...

Gene therapy for rare epilepsy shows promise in mice

2025-02-14

Dravet syndrome and other developmental epileptic encephalopathies are rare but devastating conditions that cause a host of symptoms in children, including seizures, intellectual disability, and even sudden death.

Most cases are caused by a genetic mutation; Dravet syndrome in particular is most often caused by variants in the sodium channel gene SCN1A.

Recent research from Michigan Medicine takes aim at another variant in SCN1B, which causes an even more severe form of DEE.

Mice without the SCN1B gene experience seizures and 100 percent mortality just ...

Scientists use distant sensor to monitor American Samoa earthquake swarm

2025-02-14

In late July to October 2022, residents of the Manu’a Islands in American Samoa felt the earth shake several times a day, raising concerns of an imminent volcanic eruption or tsunami.

An earthquake catalog for the area turned up nothing, because the islands lacked a seismic monitoring network that could measure the shaking and aid seismologists in their search for the source of the earthquake swarm.

But the residents of the Taʻū, Ofu, and Olosega islands needed answers, so Clara Yoon of the ...

New study explains how antidepressants can protect against infections and sepsis

2025-02-14

LA JOLLA (February 14, 2025)—Antidepressants like Prozac are commonly prescribed to treat mental health disorders, but new research suggests they could also protect against serious infections and life-threatening sepsis. Scientists at the Salk Institute have now uncovered how the drugs are able to regulate the immune system and defend against infectious disease—insights that could lead to a new generation of life-saving treatments and enhance global preparedness for future pandemics.

The Salk study follows recent findings that users of selective ...

Research reveals how Earth got its ice caps

2025-02-14

University of Leeds news

Embargoed until 14 February 2025 (19:00 GMT)

---

The cool conditions which have allowed ice caps to form on Earth are rare events in the planet’s history and require many complex processes working at once, according to new research.

A team of scientists led by the University of Leeds investigated why Earth has existed in what is known as a 'greenhouse' state without ice caps for much of its history, and why the conditions we are living in now are so rare.

They found ...

Does planetary evolution favor human-like life? Study ups odds we’re not alone

2025-02-14

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Humanity may not be extraordinary but rather the natural evolutionary outcome for our planet and likely others, according to a new model for how intelligent life developed on Earth.

The model, which upends the decades-old “hard steps” theory that intelligent life was an incredibly improbable event, suggests that maybe it wasn't all that hard or improbable. A team of researchers at Penn State, who led the work, said the new interpretation of humanity’s origin increases the probability ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Many patients want to talk about their faith. Neurologists often don't know how.

AI disclosure labels may do more harm than good

The ultra-high-energy neutrino may have begun its journey in blazars

Doubling of new prescriptions for ADHD medications among adults since start of COVID-19 pandemic

“Peculiar” ancient ancestor of the crocodile started life on four legs in adolescence before it began walking on two

AI can predict risk of serious heart disease from mammograms

New ultra-low-cost technique could slash the price of soft robotics

Increased connectivity in early Alzheimer’s is lowered by cancer drug in the lab

Study highlights stroke risk linked to recreational drugs, including among young users

Modeling brain aging and resilience over the lifespan reveals new individual factors

ESC launches guidelines for patients to empower women with cardiovascular disease to make informed pregnancy health decisions

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

Greaux Healthy Day declared in Lake Charles: Pennington Biomedical’s Greaux Healthy Initiative highlights childhood obesity challenge in SWLA

[Press-News.org] Researchers discover how opsin 3, a light-sensitive brain protein, regulates food consumption in miceResearchers at Brown University and Cincinnati Children’s found that suppressing opsin 3 in the brain of mice makes them eat less, raising new questions about the mechanisms involved in regulating human metabolism.