(Press-News.org) Modern birds are the living relatives of dinosaurs. Take a look at the features of flightless birds like chickens and ostriches that walk upright on two hind legs, or predators like eagles and hawks with their sharp talons and keen eyesight, and the similarities to small theropod dinosaurs like the velociraptors of Jurassic Park fame are striking.

Yet birds differ from their reptile ancestors in many important ways. A turning point in their evolution was the development of larger brains, which in turn led to changes in the size and shape of their skulls.

New research from the University of Chicago and University of Missouri shows how these physical changes affected the mechanics of the way birds move and use their beaks to eat and explore their habitats — adaptations that helped them evolve into the extraordinarily diverse winged creatures we see today.

The benefits of ‘wiggly’ skulls

Modern birds, as well as other animals like snakes and fishes, have skulls with jaws and palates that aren’t rigid and fixed in place like those in mammals, turtles, or non-avian dinosaurs. Alec Wilken, a graduate student in integrative biology at UChicago and lead author of the new study, calls this kind of flexible skull “wiggly.” He says this characteristic makes it that much harder to figure out how the pieces work together.

“Just because you have a joint there, that doesn't mean that you know how it moves,” Wilken said. “So, you also have to think about how muscles are going to be pulling on the joint, what kind of torque they have, and how other joints in the head limit the mobility.”

Wilken joined the project in 2015 when he was an undergraduate at the University of Missouri. Casey Holliday, PhD, Associate Professor of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences at University of Missouri, received a grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to study how the skulls, jaw muscles, and feeding mechanics changed along the transition from dinosaurs to birds, and Wilken joined his lab to help.

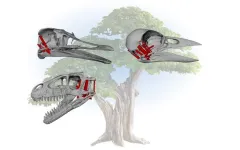

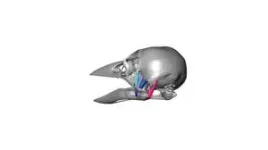

The team began by taking CT scans of a variety of fossils and skeletons from modern-day birds and related reptiles like alligators. Using the data from these images, they then built 3D models to calculate the mechanics of the skulls and jaws in action — muscle sizes and placements, their movements, and the physics involved in how they all fit together.

One of the key differences between modern birds and other animals is that they have what’s called “cranial kinesis”: the ability to move different parts of the skull independently. This gives birds an evolutionary advantage by literally expanding their palates to eat different kinds of foods or use their beaks as a multifunctional tool.

“Having a wiggly head like this really gives them a lot of evolutionary benefits,” Wilken said. Parrots, for example, can use their beaks to help climb; the extra torque helps other birds crack nuts and seeds. “In some ways, the beak functions like a surrogate hand, but being able to move the palate around while eating is also mission critical to helping them acquire food and survive.”

A cascade of changes from dinosaurs to birds

When the team analyzed data from the 3D models, they saw that as brain and skull sizes increased in non-avian theropod dinosaurs, muscles shifted into different positions that allowed the palate to separate and become mobile. These changes in turn increased muscle force, which powers cranial kinesis in most modern-day birds.

“We see this cascade of changes that happened along the dinosaur to bird transition,” Holliday said. “A large part of it hinges upon when birds evolved a relatively large brain. Just like in humans, bigger brains drive a lot of changes in the skull.”

As paleontologists discover more details about dinosaurs, the dividing line between them and modern birds becomes murky (yes, birds are technically dinosaurs, but we’re speaking in broad terms here). Scientists used to think feathers were the key, but now we know that many bona fide dinosaurs had feathers too. Flight also evolved more than once, and of course many well-known, classic dinos could fly as well.

However, flexible skulls and palates appeared later than transitional dinosaur/bird creatures like Archaeopteryx, and Holliday thinks that may become a key distinction. “Cranial kinesis might be one of the clear dividing lines between modern birds and their more dinosaur-like bird ancestors.”

The study, “Avian cranial kinesis is the result of increased encephalization during the origin of birds,” was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Additional authors include Kaleb C. Sellers from UChicago, Ian N. Cost from Albright College, Jul Davis from the University of Southern Indiana, Kevin M. Middleton from the University of Missouri, and Lawrence M. Witmer from Ohio University.

END

How big brains and flexible skulls led to the evolution of modern birds

3D modeling shows how larger brains triggered changes in jaw muscles and joint mechanics that powered a flexible feeding system for modern birds.

2025-03-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Iguanas floated one-fifth of the way around the world to colonize Fiji

2025-03-17

Iguanas have often been spotted rafting around the Caribbean on vegetation and, ages ago, evidently caught a 600-mile ride from Central America to colonize the Galapagos Islands. But for long distance travel, the Fiji iguanas can't be touched.

A new analysis conducted by biologists at the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of San Francisco (USF) suggests that sometime after about 34 million years ago, Fiji iguanas landed on the isolated group of South Pacific islands after voyaging 5,000 miles from the western coast of North America — the longest known transoceanic dispersal of any terrestrial vertebrate.

Overwater ...

‘Audible enclaves’ could enable private listening without headphones

2025-03-17

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — It may someday be possible to listen to a favorite podcast or song without disturbing the people around you, even without wearing headphones. In a new advancement in audio engineering, a team of researchers led by Yun Jing, professor of acoustics in the Penn State College of Engineering, has precisely narrowed where sound is perceived by creating localized pockets of sound zones, called audible enclaves. In an enclave, a listener can hear sound, while others standing nearby cannot, even if the people are in an enclosed space, like a vehicle, or standing ...

Twisting atomically thin materials could advance quantum computers

2025-03-17

By taking two flakes of special materials that are just one atom thick and twisting them at high angles, researchers at the University of Rochester have unlocked unique optical properties that could be used in quantum computers and other quantum technologies. In a new study published in Nano Letters, the researchers show that precisely layering nano-thin materials creates excitons—essentially, artificial atoms—that can act as quantum information bits, or qubits.

“If we had just a single ...

Impaired gastric myoelectrical rhythms associated with altered autonomic functions in patients with severe ischemic stroke

2025-03-17

Backgrounds and objectives

Gastrointestinal complications are common in patients after ischemic stroke. Gastric motility is regulated by gastric pace-making activity (also called gastric myoelectrical activity (GMA)) and autonomic function. The aim of this study was to evaluate GMA, assessed by noninvasive electrogastrography (EGG), and autonomic function, measured via spectral analysis of heart rate variability derived from the electrocardiogram in patients with ischemic stroke.

Methods

EGG and electrocardiogram were simultaneously recorded in both fasting and postprandial states in 14 patients with ischemic stroke and 11 healthy controls. ...

American College of Cardiology issues concise clinical guidance on evaluation and management of cardiogenic shock

2025-03-17

The American College of Cardiology (ACC) has issued its first Concise Clinical Guidance (CCG) to create more streamlined and efficient processes to implement best practices in patient care. This CCG focuses on evaluating and managing cardiogenic shock (CS), addressing important questions around clinical decision-making and providing actionable guidance for health care providers.

“ACC has a long history of developing clinical policy to complement clinical practice guidelines and to inform clinicians about areas where evidence is new and evolving or where randomized data is more limited. Despite this, ...

Psychological prehabilitation improves surgical recovery, study finds

2025-03-17

A new analysis led by surgeons at UCLA Health finds that psychological prehabilitation can significantly enhance recovery after surgery. The research, led by Anne E. Hall in the lab of Dr. Justine Lee analyzed data from 20 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) conducted between 2004 and 2024, involving a total of 2,376 patients. It is published in the Annals of Surgery

What is Psychological Prehabilitation? Prehabilitation is a proactive approach aimed at improving surgical outcomes through preventive measures. Traditionally, ...

Neighborhood dispute among cells: Whichever successfully exerts force wins

2025-03-17

Trial of strength at the cellular level: cells are in constant competition with each other and so eliminate diseased or unwanted cells. Cell competition is therefore a central principle for maintaining the health of tissues and organs. Researchers have investigated the success factors of superior cells and discovered a previously unknown winning strategy in mechanical cell competition. They identified a variety in the ability of cells to exert mechanical forces onto other cells as the decisive regulator. With their results ...

Deadline extended for the fifth edition of the SWIM Award for Science Journalism

2025-03-17

Milan, Italy – March 2025 – The Italian Association of Science Writers, SWIM, has announced an extension of the application deadline for the 2025 SWIM Award. Candidates now have until March 31, 2025, at 23:59 CET to submit their applications for the prestigious award, which has been recognizing excellence and innovation in science journalism in Italy since 2021.

The SWIM Award highlights the critical role of science journalists in fostering public understanding and dialogue on scientific issues. The competition also serves as the Italian selection process for the European ...

Unique dove species is the dodo of the Caribbean and in similar danger of dying out

2025-03-17

On first inspection, the Cuban blue-headed quail dove doesn’t look like much: drab brown feathers, a slender beak, a pronounced strut in their walk typical of most other doves. You’d be forgiven for overlooking it in favor of Cuba’s prismatic parrots. But looks aren’t everything. For decades, this unassuming bird has perplexed biologists, who have no idea where it came from, how it got to the island or what it’s related to.

Now, for the first time, scientists have sequenced DNA from the blue-headed quail dove with the goal of finally getting to the bottom of things. Instead, they’re even more perplexed now than when they started.

“This ...

Free University Brussels (VUB) opens its doors to censored American researchers

2025-03-17

The Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB) is opening 12 postdoctoral positions for international researchers, with a specific focus on American scholars working in socially significant fields. These prestigious fellowships come with substantial funding (€2.5 million) as part of the European Marie Skłodowska-Curie (MSCA) program. Additionally, as part of the Brains for Brussels initiative, VUB aims to actively attract American professors looking to relocate. In collaboration with its Francophone sister university ULB, VUB is also providing 18 apartments for international ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Low testosterone, high fructose: A recipe for liver disaster

SKKU research team unravels the origin of stochasticity, a key to next-generation data security and computing

Flexible polymer‑based electronics for human health monitoring: A safety‑level‑oriented review of materials and applications

Could ultrasound help save hedgehogs?

attexis RCT shows clinically relevant reduction in adult ADHD symptoms and is published in Psychological Medicine

Cellular changes linked to depression related fatigue

First degree female relatives’ suicidal intentions may influence women’s suicide risk

Specific gut bacteria species (R inulinivorans) linked to muscle strength

Wegovy may have highest ‘eye stroke’ and sight loss risk of semaglutide GLP-1 agonists

New African species confirms evolutionary origin of magic mushrooms

Mining the dark transcriptome: University of Toronto Engineering researchers create the first potential drug molecules from long noncoding RNA

IU researchers identify clotting protein as potential target in pancreatic cancer

Human moral agency irreplaceable in the era of artificial intelligence

Racial, political cues on social media shape TV audiences’ choices

New model offers ‘clear path’ to keeping clean water flowing in rural Africa

Ochsner MD Anderson to be first in the southern U.S. to offer precision cancer radiation treatment

Newly transferred jumping genes drive lethal mutations

Where wells run deep, biodiversity runs thin

Q&A: Gassing up bioengineered materials for wound healing

From genetics to AI: Integrated approaches to decoding human language in the brain

Leora Westbrook appointed executive director of NR2F1 Foundation

Massive-scale spatial multiplexing with 3D-printed photonic lanterns achieved by researchers

Younger stroke survivors face greater concentration, mental health challenges — especially those not employed

From chatbots to assembly lines: the impact of AI on workplace safety

Low testosterone levels may be associated with increased risk of prostate cancer progression during surveillance

Analysis of ancient parrot DNA reveals sophisticated, long-distance animal trade network that pre-dates the Inca Empire

How does snow gather on a roof?

Modeling how pollen flows through urban areas

Blood test predicts dementia in women as many as 25 years before symptoms begin

Female reproductive cancers and the sex gap in survival

[Press-News.org] How big brains and flexible skulls led to the evolution of modern birds3D modeling shows how larger brains triggered changes in jaw muscles and joint mechanics that powered a flexible feeding system for modern birds.