(Press-News.org) For decades, atomic clocks have been the pinnacle of precision timekeeping, enabling GPS navigation, cutting-edge physics research, and tests of fundamental theories. But researchers at JILA, led by JILA and NIST Fellow and University of Colorado Boulder physics professor Jun Ye, in collaboration with the Technical University of Vienna, are pushing beyond atomic transitions to something potentially even more stable: a nuclear clock. This clock could revolutionize timekeeping by using a uniquely low-energy transition within the nucleus of a thorium-229 atom. This transition is less sensitive to environmental disturbances than modern atomic clocks and has been proposed for tests of fundamental physics beyond the Standard Model.

This idea isn’t new in Ye’s laboratory. In fact, work in the lab on nuclear clocks began with a landmark experiment, the results of which were published as the cover article of Nature last year, where the team made the first frequency-based, quantum-state-resolved measurement of the thorium-229 nuclear transition in a thorium-doped host crystal. This achievement confirmed that thorium’s nuclear transition could be measured with enough precision to be used as a timekeeping reference.

However, to build a precise clock, researchers must fully characterize how the transition responds to external conditions, including temperature. That’s where this new investigation—an “Editor’s Choice” paper published in Physical Review Letters—comes in, as the team studied the energy shifts in the thorium nuclei as the crystal containing the atoms was heated to different temperatures.

“This is the first step toward characterizing the systematics of the nuclear clock,” says JILA postdoctoral researcher Dr. Jacob Higgins, the study's first author. “We have found a transition that’s relatively insensitive to temperature, which is exactly what we want for a precision timekeeping device.”

“A solid-state nuclear clock has a great potential to become a robust and portable timing device that is highly precise,” notes Jun Ye. “We are searching for the parameter space for a compact nuclear clock to maintain 10-18 fractional frequency stability for continuous operation.”

The Precision of Nuclear Clocks

Because the nucleus of an atom is less affected by environmental disturbances than its electrons, a nuclear clock could retain accuracy under conditions where atomic clocks would falter, as the clock is more resistant to noise. Among all other nuclei, thorium-229 is particularly well-suited for this because it has a nuclear transition with unusually low energy, making it possible to probe with ultraviolet laser light rather than high-energy gamma rays.

As opposed to measuring thorium in a trapped ion system, the Ye lab has taken a different approach: embedding thorium-229 into a solid-state host—a calcium fluoride (CaF₂) crystal. This method, developed by their collaborators at the Technical University of Vienna, allows for a much higher density of thorium nuclei than traditional ion-trap techniques. More nuclei means stronger signals and better stability for measuring the nuclear transition.

Heating a Nuclear Clock

To look at how temperature affects this nuclear transition, the researchers both cooled and heated the thorium-doped crystal to three different temperatures: 150K (-123°C) with liquid nitrogen, 229K (-44°C) with a dry ice-methanol mixture, and 293K (around room temperature). Using a frequency comb laser, they measured how the nuclear transition frequency shifted at each temperature, revealing two competing physical effects within the crystal.

For one effect, as the crystal warmed, it expanded, subtly altering the atomic lattice and shifting the electric field gradients experienced by the thorium nuclei. This electric field gradient caused the thorium transition to split into multiple spectral lines, which shifted in different directions as the temperature changed. The second effect is that the lattice expansion also changed the charge density of electrons in the crystal, modifying the electrons’ interaction strength with the nucleus and causing the spectral lines to move in the same direction.

As these two effects fought for control of the thorium atoms, one particular transition was observed to be far less temperature-sensitive than the others, as the two effects mostly canceled each other out. Across the full temperature range examined, this transition shifted by only 62 kilohertz, a shift at least 30 times smaller than in the other transitions.

“This transition is behaving in a way that’s really promising for clock applications,” adds Chuankun Zhang, a JILA graduate student. “If we can stabilize it further, it could be a real game-changer in precision timekeeping.”

As a next step, the team plans to look for a temperature ‘sweet spot’ where the nuclear transition remains almost completely independent of temperature. Their initial data suggests that somewhere between 150K and 229K, the transition frequency would be even easier to temperature stabilize, providing an ideal operating condition for a future nuclear clock.

Customizing a Nuclear Clock System

Building an entirely new type of clock requires one-of-a-kind-designed equipment, much of which doesn’t exist to the level of customization required. Thanks to JILA’s instrument shop—with its machinists and engineers—the team was able to create critical components for their experiment.

“Kim Hagan and the whole instrument shop have been super helpful throughout this process,” Higgins notes. “They machined the crystal mount, which holds the thorium-doped crystal, and built parts of the cold trap system that allowed us to control the temperature precisely.”

Having in-house machining expertise allowed the researchers to quickly iterate on designs and ensure that even small changes—such as swapping out the crystal—could be done with ease.

“If we only had used off-the-shelf parts, we wouldn’t have had the same level of confidence in our setup,” adds JILA graduate student Tian Ooi, another team member. “The custom-built pieces from the instrument shop save us so much time.”

Sensing Beyond Time

While the primary goal of this research is to develop a more stable nuclear clock, its implications go beyond timekeeping. The thorium nuclear transition is very insensitive to disturbances in its environment, but highly sensitive to variations in fundamental forces—any unexpected shift in its frequency could indicate new physics, such as the presence of dark matter.

“The nuclear transition’s sensitivity could allow us to probe new physics,” Higgins explains. “Beyond just making a better clock, this could open doors to entirely new ways of studying the universe.”

This research was supported by the Army Research Office, the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, the National Science Foundation, the Quantum System Accelerator, and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

END

Dialing in the temperature needed for precise nuclear timekeeping

2025-03-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Fewer than half of Medicaid managed care plans provide all FDA-approved medications for alcohol use disorder

2025-03-17

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Monday, March 17, 2025

Contact:

Jillian McKoy, jpmckoy@bu.edu

Michael Saunders, msaunder@bu.edu

##

As health complications and deaths from alcohol use disorder (AUD) increase in the United States, it is critical that people who could benefit from medications have access to the drugs that the US Food and Drug Administration has approved to treat AUD. Yet, for individuals who have alcohol use disorder and are covered by Medicaid, accessing these medications is difficult; past research indicates that only about 1 in 20 Medicaid enrollees with alcohol use disorder receive these ...

Mount Sinai researchers specific therapy that teaches patients to tolerate stomach and body discomfort improved functional brain deficits linked to visceral disgust that can cause of food avoidance in

2025-03-17

Mount Sinai Researchers Find Specific Therapy That Teaches Patients to Tolerate Stomach and Body Discomfort Improved Functional Brain Deficits Linked to Visceral Disgust That Can Cause Food Avoidance in Adolescent Females with Anorexia Nervosa and other Low-Weight Eating Disorders

Corresponding Author: Kurt P. Schulz, PhD, Associate Professor, Center of Excellence in Eating and Weight Disorders, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and other co-authors

Bottom Line: A trial of interoceptive exposure - a therapy that teaches patients how to tolerate stomach and body discomfort in order to reduce restrictive eating - improved functional deficits in a brain region ...

New ACP guideline recommends combination therapy for acute episodic migraines

2025-03-17

Follow @Annalsofim on X, Facebook, Instagram, threads, and Linkedin

Below please find summaries of new articles that will be published in the next issue of Annals of Internal Medicine. The summaries are not intended to substitute for the full articles as a source of information. This information is under strict embargo and by taking it into possession, media representatives are committing to the terms of the embargo not only on their own behalf, but also on behalf ...

Last supper of 15-million-year-old freshwater fish

2025-03-17

18th March 2025, Sydney: In an Australian first, a team of scientists led by Australian Museum and UNSW Sydney palaeontologist, Dr Matthew McCurry, have described a new species of 15-million-year-old fossilised freshwater fish, Ferruaspis brocksi, that shows preserved stomach contents as well as the pattern of colouration. The research is published today in The Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology (DOI - 10.1080/02724634.2024.2445684)

Named after Professor Jochen J. Brocks from the Australian National University, who discovered several of the fossilised species at the Australian Museum’s, McGraths Flat fossil site near Gulgong, NSW, Ferruaspis brocksi is the first ...

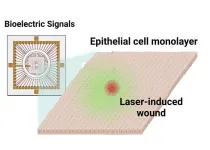

Slow, silent ‘scream’ of epithelial cells detected for first time

2025-03-17

EMBARGOED UNTIL 3/17/2025, 3:00PM ET

March 17, 2025

Slow, Silent ‘Scream’ of Epithelial Cells Detected for First Time

Team from UMass Amherst uncovers communication by “electric spiking” in cells once thought to be mute, which could enable bioelectric applications

AMHERST, Mass. — It has long been thought that only nerve and heart cells use electric impulses to communicate, while epithelial cells — which compose the linings of our skin, organs ...

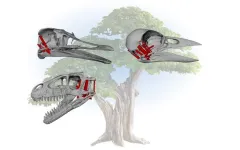

How big brains and flexible skulls led to the evolution of modern birds

2025-03-17

Modern birds are the living relatives of dinosaurs. Take a look at the features of flightless birds like chickens and ostriches that walk upright on two hind legs, or predators like eagles and hawks with their sharp talons and keen eyesight, and the similarities to small theropod dinosaurs like the velociraptors of Jurassic Park fame are striking.

Yet birds differ from their reptile ancestors in many important ways. A turning point in their evolution was the development of larger brains, which in turn led to changes in the size and shape of their skulls.

New research from ...

Iguanas floated one-fifth of the way around the world to colonize Fiji

2025-03-17

Iguanas have often been spotted rafting around the Caribbean on vegetation and, ages ago, evidently caught a 600-mile ride from Central America to colonize the Galapagos Islands. But for long distance travel, the Fiji iguanas can't be touched.

A new analysis conducted by biologists at the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of San Francisco (USF) suggests that sometime after about 34 million years ago, Fiji iguanas landed on the isolated group of South Pacific islands after voyaging 5,000 miles from the western coast of North America — the longest known transoceanic dispersal of any terrestrial vertebrate.

Overwater ...

‘Audible enclaves’ could enable private listening without headphones

2025-03-17

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — It may someday be possible to listen to a favorite podcast or song without disturbing the people around you, even without wearing headphones. In a new advancement in audio engineering, a team of researchers led by Yun Jing, professor of acoustics in the Penn State College of Engineering, has precisely narrowed where sound is perceived by creating localized pockets of sound zones, called audible enclaves. In an enclave, a listener can hear sound, while others standing nearby cannot, even if the people are in an enclosed space, like a vehicle, or standing ...

Twisting atomically thin materials could advance quantum computers

2025-03-17

By taking two flakes of special materials that are just one atom thick and twisting them at high angles, researchers at the University of Rochester have unlocked unique optical properties that could be used in quantum computers and other quantum technologies. In a new study published in Nano Letters, the researchers show that precisely layering nano-thin materials creates excitons—essentially, artificial atoms—that can act as quantum information bits, or qubits.

“If we had just a single ...

Impaired gastric myoelectrical rhythms associated with altered autonomic functions in patients with severe ischemic stroke

2025-03-17

Backgrounds and objectives

Gastrointestinal complications are common in patients after ischemic stroke. Gastric motility is regulated by gastric pace-making activity (also called gastric myoelectrical activity (GMA)) and autonomic function. The aim of this study was to evaluate GMA, assessed by noninvasive electrogastrography (EGG), and autonomic function, measured via spectral analysis of heart rate variability derived from the electrocardiogram in patients with ischemic stroke.

Methods

EGG and electrocardiogram were simultaneously recorded in both fasting and postprandial states in 14 patients with ischemic stroke and 11 healthy controls. ...