(Press-News.org) Washington, D.C. — It is difficult to measure accurately each nation's contribution of carbon dioxide to the Earth's atmosphere. Carbon is extracted out of the ground as coal, gas, and oil, and these fuels are often exported to other countries where they are burned to generate the energy that is used to make products. In turn, these products may be traded to still other countries where they are consumed. A team led by Carnegie's Steven Davis, and including Ken Caldeira, tracked and quantified this supply chain of global carbon dioxide emissions. Their work will be published online by Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences during the week of October 17.

Traditionally, the carbon dioxide emitted by burning fossil fuels is attributed to the country where the fuels were burned. But until now, there has not yet been a full accounting of emissions taking into consideration the entire supply chain, from where fuels originate all the way to where products made using the fuels are ultimately consumed.

"Policies seeking to regulate emissions will affect not only the parties burning fuels but also those who extract fuels and consume products. No emissions exist in isolation, and everyone along the supply chain benefits from carbon-based fuels," Davis said.

He and Caldeira, along with Glen Peters from the Center for International Climate and Environmental Research in Oslo, Norway, based their analysis on fossil energy resources of coal, oil, natural gas, and secondary fuels traded among 58 industrial sectors and 112 countries in 2004.

They found that fossil resources are highly concentrated and that the majority of fuel that is exported winds up in developed countries. Most of the countries that import a lot of fossil fuels also tend to import a lot of products. China is a notable exception to this trend.

Davis and Caldeira say that their results show that enacting carbon pricing mechanisms at the point of extraction could be efficient and avoid the relocation of industries that could result from regulation at the point of combustion. Manufacturing of goods may shift from one country to another, but fossil fuel resources are geographically fixed.

They found that regulating the fossil fuels extracted in China, the US, the Middle East, Russia, Canada, Australia, India, and Norway would cover 67% of global carbon dioxide emissions. The incentive to participate would be the threat of missing out on revenues from carbon-linked tariffs imposed further down the supply chain.

Incorporating gross domestic product into these analyses highlights which countries' economies are most reliant on domestic resources of fossil energy and which economies are most dependent on traded fuels.

"The country of extraction gets to sell their products and earn foreign exchange. The country of production gets to buy less-expensive fuels and therefore sell less-expensive products. The country of consumption gets to buy products at lower cost." Caldeira said. "However, we all have an interest in preventing the climate risk that the use of these fuels entails."

###

To look at the data, visit: http://supplychainco2.stanford.edu/.

The Department of Global Ecology was established in 2002 to help build the scientific foundations for a sustainable future. The department is located on the campus of Stanford University, but is an independent research organization funded by the Carnegie Institution. Its scientists conduct basic research on a wide range of large-scale environmental issues, including climate change, ocean acidification, biological invasions, and changes in biodiversity.

The Carnegie Institution for Science (carnegiescience.edu) is a private, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C., with six research departments throughout the U.S. Since its founding in 1902, the Carnegie Institution has been a pioneering force in basic scientific research. Carnegie scientists are leaders in plant biology, developmental biology, astronomy, materials science, global ecology, and Earth and planetary science.

Links in the chain: Global carbon emissions and consumption

2011-10-19

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2011 a banner year for young striped bass in Virginia

2011-10-19

Preliminary results from a 2011 survey conducted by researchers at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) suggest the production of a strong class of young-of-year striped bass in the Virginia portion of Chesapeake Bay. The 2011 year class represents the group of fish hatched this spring.

The results are good news for the recreational and commercial anglers who pursue this popular game fish because this year class is expected to grow to fishable size in 3 to 4 years. The results are also good news for Chesapeake Bay, where striped bass play an important ecological ...

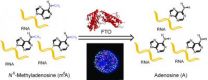

New research links common RNA modification to obesity

2011-10-19

An international research team has discovered that a pervasive human RNA modification provides the physiological underpinning of the genetic regulatory process that contributes to obesity and type II diabetes.

European researchers showed in 2007 that the FTO gene was the major gene associated with obesity and type II diabetes, but the details of its physiological and cellular functioning remained unknown.

Now, a team led by University of Chicago chemistry professor Chuan He has demonstrated experimentally the importance of a reversible RNA modification process mediated ...

NewBlueFX Announces Titler Pro Bundle With Sony Vegas Pro 11

2011-10-19

Innovative video effects creator and technology developer NewBlue, Inc. announces the inclusion of their new Titler Pro with Vegas Pro 11 from Sony, along with 13 other NewBlue plug-ins from 6 best-selling video plug-in collections. NewBlue Titler Pro (MSRP $299.95) is designed for the professional editor's schedule; to make it easy for editors to quickly create 2D & 3D graphics on a timeline.

Titler Pro title animations use the computer's GPU to blend sophisticated 3D modeling with 2D raster processing to generate imagery in real time. Titler Pro also boasts an ...

Farmland floods do not raise levels of potentially harmful flame retardants in milk

2011-10-19

WASHINGTON, Oct. 12, 2011 — As millions of acres of farmland in the U.S. Midwest and South recover from Mississippi River flooding, scientists report that river flooding can increase levels of potentially harmful flame retardants in farm soils. But the higher levels apparently do not find their way into the milk produced by cows that graze on these lands.

That's the reassuring message in the latest episode in the American Chemical Society's (ACS) award-winning "Global Challenges/Chemistry Solutions" podcast series.

Iain Lake, Ph.D., notes in the podcast that the flame ...

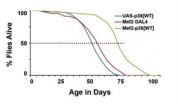

Muscling toward a longer life: Genetic aging pathway identified in flies

2011-10-19

Researchers at Emory University School of Medicine have identified a set of genes that act in muscles to modulate aging and resistance to stress in fruit flies.

Scientists have previously found mutations that extend fruit fly lifespan, but this group of genes is distinct because it acts specifically in muscles. The findings could help doctors better understand and treat muscle degeneration in human aging.

The results were published online this week by the journal Developmental Cell.

The senior author is Subhabrata Sanyal, PhD, assistant professor of cell biology at ...

"Impact of US Domestic Tonnage Regulations on Design, Maintenance and Manning" Topic of Free WorkBoat.com Webinar on October 26

2011-10-19

Designing a vessel to meet a tonnage parameter has proven to be the bane of designers, builders and owners since the earliest days of the maritime industry. Today, regulations initially established over 140 years ago in a surveyor's office in London can dramatically affect the construction of virtually every commercial vessel at work in the United States.

"Every boat needs to have a tonnage certificate for whatever its type of function and any modification to a vessel can result in ramifications to the tonnage certificate," said David Krapf, editor in chief ...

Amorphous diamond, a new super-hard form of carbon created under ultrahigh pressure

2011-10-19

An amorphous diamond – one that lacks the crystalline structure of diamond, but is every bit as hard – has been created by a Stanford-led team of researchers.

But what good is an amorphous diamond?

"Sometimes amorphous forms of a material can have advantages over crystalline forms," said Yu Lin, a Stanford graduate student involved in the research.

The biggest drawback with using diamond for purposes other than jewelry is that even though it is the hardest material known, its crystalline structure contains planes of weakness. Those planes are what allow diamond ...

Canadian Pharmacy Customers Save Big on Wellbutrin XL

2011-10-19

Canada Drug Pharmacy offers Wellbutrin XL at a cheaper price, much cheaper when compared to purchasing the same drug from traditional retail stores. As more and more people turn to the internet to shop online, they are also searching for ways to save money. One of the benefits of buying Canadian drugs from CanadaDrugPharmacy.com is that the price of prescription medications is cheaper than traditional brick and mortar pharmacies. Purchasing online is also convenient since the consumers don't have to leave their house to buy their medicine. Customers can now log-in to Canada ...

Chinese-Americans don't overborrow, MU study finds

2011-10-19

COLUMBIA, Mo. – Bad mortgage loans and rampant consumer debt were two of the primary causes for the recent economic recession in the U.S. Despite a national trend of debt problems, a University of Missouri researcher has found one American population that holds almost no consumer debt outside of typical home mortgages. Rui Yao, an assistant professor of personal financial planning in the College of Human Environmental Sciences at the University of Missouri, found that while 72 percent of Chinese-American households hold a mortgage, only five percent of those households ...

Impurity atoms introduce waves of disorder in exotic electronic material

2011-10-19

UPTON, NY - It's a basic technique learned early, maybe even before kindergarten: Pulling things apart - from toy cars to complicated electronic materials - can reveal a lot about how they work. "That's one way physicists study the things that they love; they do it by destroying them," said Séamus Davis, a physicist at the U.S. Department of Energy's (DOE) Brookhaven National Laboratory and the J.G. White Distinguished Professor of Physical Sciences at Cornell University.

Davis and colleagues recently turned this destructive approach - and a sophisticated tool for "seeing" ...