(Press-News.org) AUGUSTA, Ga. – Examining the chin and upper and lower abdomen is a reliable, minimally invasive way to screen for excessive hair growth in women, a key indicator of too much male hormone, researchers report.

"We wanted to find a way to identify this problem in women that was as non-intrusive and accurate as possible," said Dr. Ricardo Azziz, reproductive endocrinologist and President of Georgia Health Sciences University.

"We believe this approach is approximately 80 percent accurate and will be less traumatic for women in many situations than the full body assessments currently used," said Azziz, corresponding author of the study published in the journal Fertility and Sterility.

In addition to cosmetic concerns, women with excessive hair growth, or hirsutism, are often overweight with menstrual dysfunction and diminished fertility related to problems with ovulation. Symptoms can begin in childhood. Hirsutism also is highly correlated with polycystic ovary syndrome, or PCOS, a major cause of infertility as well as a significant risk factor for diabetes and heart disease. PCOS is a subcategory of androgen excess or excess male hormone, the most common hormone disorder, which affects about 10 percent of women.

"If you do the math, at least half the women with excess hair growth will be at increased risk for insulin resistance, metabolic dysfunction, diabetes and heart disease. That is why this is such an important marker," Azziz said.

He calls hirsutism the single most defining feature of androgen excess disorder, such as PCOS. "Excessive hair growth strikes at the femininity of women. We are talking about terminal hairs that are harder, more pigmented and thicker than the usual soft hairs you see." In fact, Azziz and his colleagues have previously published studies indicating hirsutism is second to obesity in negatively impacting a woman's quality of life. "You cover yourself up at the beach. You don't want your partner to see you nude. It can be very damaging to your psychosocial well-being," he said.

The most widely used assessment today is about 50 years old and includes nine body areas: the lip, chin, chest, upper and lower abdomen, upper arm, thigh and upper and lower back. Many women consider this full body check invasive and it can be unwieldy for scientists doing large epidemiologic studies, Azziz said.

For this study, Azziz examined 1,116 female patients at the University of Alabama at Birmingham from 1987-2002 and 835 female patients at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles from 2003-09 with symptoms of androgen excess. Study authors note the method needs further evaluation, including whether it can be used to monitor success of hirsutism treatment.

The hirsutism study is part of Azziz's ongoing research of the problems related to androgen excess and PCOS.

Diagnosis is a complex process that can include a history and physical exam, quantifying hair growth, measuring male hormone levels as well as an oral glucose tolerance test to determine the degree of insulin excess and diabetes risk, said Azziz's collaborator, Dr. Lawrence C. Layman, chief of the GHSU Section of Reproductive Endocrinology, Infertility and Genetics. It also requires ruling out syndromes or disorders with similar symptoms such as non-classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia, which Azziz's team helped differentiate. Current therapies, such as birth control pills to prevent androgen synthesis and the blood pressure medicine, spironolactone, a diuretic that also blocks androgen receptors, treat symptoms rather than causes, the researchers said.

To improve diagnosis and treatment, they along with Azziz's long time colleagues Dr. Yen-Hao Chen, biomedical scientist, and Saleh Heneidi, research associate, are expanding the GHSU Tissue Repository for Androgen-Related Disorders. In the past two decades, Azziz's team has collected more than 50,000 samples – including fat, blood, urine, plasma and DNA – from about 7,000 women. Having this variety of samples, particularly from the same woman, enables the scientists to better put together the pieces that contribute to the syndrome, Chen said.

"These women have been to a lot of doctors and a lot of clinics and they know that the medical knowledge out there is limited so they are willing to help further research in this field," Azziz said of the significant patient contributions.

Azziz is collaborating with scientists at Cedars-Sinai to identify the multiple genes responsible, which they suspect also have roles in insulin signaling, inflammation and androgen production. "We know that a significant portion of women with PCOS have an inherited defect of their insulin action which, along with other genetic defects, results in the syndrome," he said. "If we can find the genes that are abnormal, we may be able to find drugs to target those genes."

His GHSU team is also examining signaling abnormalities in fat – a determinant of insulin resistance – in PCOS patients. "Clearly fat in PCOS behaves differently than fat in healthy women of the same weight," Azziz said. They suspect the abnormal signals are partially to blame for the abnormal response to insulin. They also suspect the signaling abnormalities are good treatment targets.

INFORMATION:

Co-authors on the hirsutism study are Dr. Heather Cook, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, UCLA, and Dr. Kathleen Brennan, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, UCLA and Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and Helping Hands of Los Angeles, Inc. Azziz came to GHSU from Cedars Sinai and UCLA in July 2010.

For more information about the Tissue Repository for Androgen-Related Disorders, contact Brenda Rosson, research coordinator, at brosson@georgiahealth.edu.

Women's chin, abdomen are good indicators of excessive hair growth

2011-11-03

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

The Hong Kong Meteorite Website Release

2011-11-03

At present, with the amount of domestic meteorite collectors increasing rapidly, meteorite collection is becoming more and more popular. The website http://www.meteorite.hk was born as an answer to these times.

The Hong Kong meteorite website was founded by the Hong Kong Best Tone Group Limited; it is not just a professional platform to show meteorites, but also a transaction platform for the meteorite collectors from all over the world and it will provide an international campaign.

The Hong Kong meteorite website was identified by the major meteorite authority; it ...

Amazing catalysts: American Chemical Society's latest Prized Science video

2011-11-03

WASHINGTON, Nov. 2, 2011 — Just as people who have the enthusiasm and energy to make things happen are called catalysts, their namesakes — chemical catalysts — also are facilitators, jump-starting chemical reactions that would never work or would work too slowly. Almost everything we rely upon in everyday life — 90 percent of all commercially produced products (a trillion dollars worth each year) — involve catalysts at some stage of their manufacture.

A new episode in the 2011 edition of a popular video series from the American Chemical Society (ACS), the world's largest ...

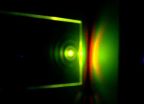

Solar concentrator increases collection with less loss

2011-11-03

Converting sunlight into electricity is not economically attractive because of the high cost of solar cells, but a recent, purely optical approach to improving luminescent solar concentrators (LSCs) may ease the problem, according to researchers at Argonne National Laboratories and Penn State.

Using concentrated sunlight reduces the cost of solar power by requiring fewer solar cells to generate a given amount of electricity. LSCs concentrate light by absorbing and re-emiting it at lower frequency within the confines of a transparent slab of material. They can not only ...

Animal study suggests that newborn period may be crucial time to prevent later diabetes

2011-11-03

Pediatric researchers who tested newborn animals with an existing human drug used in adults with diabetes report that this drug, when given very early in life, prevents diabetes from developing in adult animals. If this finding can be repeated in humans, it may become a way to prevent at-risk infants from developing type 2 diabetes.

"We uncovered a novel mechanism to prevent the later development of diabetes in this animal study," said senior author Rebecca A. Simmons, M.D., a neonatologist at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. "This may indicate that there is an ...

News tips from the journal mBio

2011-11-03

Antibodies Trick Bacteria into Killing Each Other

The dominant theory about antibodies is that they directly target and kill disease-causing organisms. In a surprising twist, researchers from the Albert Einstein College of Medicine have discovered that certain antibodies to Streptococcus pneumoniae actually trick the bacteria into killing each other.

Pneumococcal vaccines currently in use today target the pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide (PPS), a sort of armor that surrounds the bacterial cell, protecting it from destruction. Current thought hold that PPS-binding ...

Solar power could get boost from new light absorption design

2011-11-03

Solar power may be on the rise, but solar cells are only as efficient as the amount of sunlight they collect. Under the direction of a new professor at Northwestern University's McCormick School of Engineering and Applied Science, researchers have developed a new material that absorbs a wide range of wavelengths and could lead to more efficient and less expensive solar technology.

A paper describing the findings, "Broadband polarization-independent resonant light absorption using ultrathin plasmonic super absorbers," was published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications.

"The ...

Exenatide (Byetta) has rapid, powerful anti-inflammatory effect, UB study shows

2011-11-03

BUFFALO, N.Y. -- Exenatide, a drug commonly prescribed to help patients with type 2 diabetes improve blood sugar control, also has a powerful and rapid anti-inflammatory effect, a University at Buffalo study has shown.

The study of the drug, marketed under the trade name Byetta, was published recently in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism.

"Our most important finding was this rapid, anti-inflammatory effect, which may lead to the inhibition of atherosclerosis, the major cause of heart attacks, strokes and gangrene in diabetics," says Paresh Dandona, ...

Manufacturing microscale medical devices for faster tissue engineering

2011-11-03

WASHINGTON, Nov. 2—In the emerging field of tissue engineering, scientists encourage cells to grow on carefully designed support scaffolds. The ultimate goal is to create living structures that might one day be used to replace lost or damaged tissue, but the manufacture of appropriately detailed scaffolds presents a significant challenge that has kept most tissue engineering applications confined to the research lab. Now a team of researchers from the Laser Zentrum Hannover (LZH) eV Institute in Hannover, Germany, and the Joint Department of Biomedical Engineering at the ...

Dirt prevents allergy

2011-11-03

Oversensitivity diseases, or allergies, now affect 25 per cent of the population of Denmark. The figure has been on the increase in recent decades and now researchers at the Copenhagen Prospective Studies on Asthma in Childhood (COPSAC), University of Copenhagen, are at last able to partly explain the reasons.

"In our study of over 400 children we observed a direct link between the number of different bacteria in their rectums and the risk of development of allergic disease later in life," says Professor Hans Bisgaard, consultant at Gentofte Hospital, head of the Copenhagen ...

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance now an important first-line test

2011-11-03

Philadelphia, PA, November 2, 2011 – Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (CMR) has undergone substantial development and offers important advantages compared with other well-established imaging modalities. In the November/December issue of Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, published by Elsevier, a series of articles on key topics in CMR will foster greater understanding of the rapidly expanding role of CMR in clinical cardiology.

"Until a decade ago, CMR was considered mostly a research tool, and scans for clinical purpose were rare," stated guest editors Theodoros ...