(Press-News.org)

VIDEO:

This 12-second video shows the formation of particle strings at angles perpendicular to the direction of shear flow. Many scientists had predicted that the strings would form parallel to the...

Click here for more information.

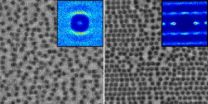

Microscopic spheres form strings in surprising alignments when suspended in a viscous fluid and sheared between two plates — a finding that will affect the way scientists think about the properties of such wide-ranging substances as shampoo and futuristic computer chips.

A team of scientists at Cornell University and the University of Chicago have imaged this behavior and have explained the forces causing it for the first time. Its findings appear in the Dec. 19-23 early edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"The experimental breakthrough revealed that these string structures were perpendicular to the shear instead of parallel to it, contrary to what many in the field were expecting," said Aaron Dinner, associate professor in chemistry at UChicago and a study co-author.

The experiment was led by Itai Cohen, associate professor of physics at Cornell, who custom-built a device that would enable him simultaneously to exert shearing forces on suspended colloids (the spheres) and image the resulting motion at 100 frames per second with a confocal microscope. Imaging speed was critical to the experiment because the string-like structures appear only at certain shear rates.

"This issue of strings has been pretty controversial. I'm not sure that we've solved all the controversies associated with them, but at least we've made a step forward," Cohen said.

Shearing forces affect the dynamic behavior of paint, shampoo and other viscous household products, but an understanding of these and related phenomena at the microscopic level has largely eluded a detailed scientific understanding until the last decade, Dinner noted.

Futuristically speaking, these forces potentially could be harnessed to produce microscopic patterns on computer chips or biosensors via special paints that flow easily when layered in one direction, but becomes hard when layered in another direction.

Cohen's objective was more scientifically immediate: to devise an experiment that would overcome the technical difficulties associated with measuring the mechanical properties of the colloidal strings while also imaging their formation. "The holy grail is to be able to understand how the structure leads to the mechanical properties and then to be able to control the mechanical properties by influencing the structure," Cohen explained.

Cohen, PhD'01, received his doctorate in physics at UChicago, as did lead author Xiang Cheng, PhD'09, a postdoctoral associate at Cornell who assembled the team; and co-author Xinliang Xu, PhD'07, a postdoctoral scholar at UChicago. The study co-authors also included Stuart Rice, the Frank P. Hixon Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus in Chemistry at UChicago and a 1999 recipient of the National Medal of Science.

As members of UChicago's Materials Research Science and Engineering Center, Rice and Dinner are part of a larger effort to determine how materials behave under the influence of various dynamic forces. Some of their physics colleagues analyze forces operating on macroscopic scales, while chemists such as Rice and Dinner attempt to assess how those findings might apply to microscopic phenomena.

Rice and his UChicago co-authors used computer simulations to develop a precise explanation for the string-like colloidal structures that formed in the Cornell experiment. "The previous simulations all left out the consequences of the flow created in the supporting fluid as the particles move, the so-called hydrodynamic forces," Rice said.

"A very large fraction of the work in the field neglects hydrodynamic forces because it's hard. You try and get away with what you can," Rice noted with amusement. "But in this case it turns out that the inclusion of those forces is the crucial element."

The simulations allowed the UChicago team to control various experimental parameters to assess their relative importance. "You can play God," Rice said. "The important finding is the overwhelming role of the lubrication forces and the anti-intuitive result that they create."

The lubrication force comes into play when two colloids come together to behave much like macroscopic ball bearings soaking in a reservoir of goopy fluid.

"Pulling them apart would be working against the fluid and so it would be very hard," Dinner said. "So actually, when you get a collision in these colloidal systems, those lubrication forces hold them together much longer, and that actually allows for some of the unique dynamics that give rise to the structure. That was specifically what the simulations showed."

Xu, the UChicago postdoctoral scholar, adapted a mathematical formula developed by John Brady at the California Institute of Technology to simplify the simulations, which ran for days and weeks at a time. "Every time you rearrange the particles, the interactions are different," Rice said. "If you were to calculate that directly, it would be extremely tedious."

But Xu's adapation of Brady's formula enabled him to generate a table of hydrodynamic interactions that listed each particle configuration. Xu found that he could accurately simplify the simulation by focusing on just two of the experiment's seven layers of colloids.

The simulations and the experiment showed that even after three centuries of study, the field of hydrodynamics continues to yield surprising discoveries. "We are still discovering novel behavior that is fundamentally determined by the hydrodynamics," Rice noted.

INFORMATION:

Citation: "Assembly of vorticity-aligned hard-sphere colloidal strings in a simple shear flow," by Xiang Chen, Xinliang Xu, Stuart A. Rice, Aaron R. Dinner, and Itai Cohen, Dec.19-23 early edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Funding: U.S. Department of Energy, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, and the National Science Foundation.

Shearing triggers odd behavior in microscopic particles

2011-12-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A new way of approaching the early detection of Alzheimer's disease

2011-12-27

One of our genes is apolipoprotein E (APOE), which often appears with a variation which nobody would want to have: APOEε4, the main genetic risk factor for sporadic Alzheimer's disease (the most common form in which this disorder manifests itself and which is caused by a combination of hereditary and environmental factors). It is estimated that at least 40% of the sporadic patients affected by this disease are carriers of APOEε4, but this also means that much more still remains to be studied. The researcher at the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU) Xabier ...

Viagra against heart failure: Researchers at the RUB and from Rochester throw light on the mechanism

2011-12-27

How sildenafil, the active ingredient in Viagra, can alleviate heart problems is reported by Bochum's researchers in cooperation with colleagues from the Mayo Clinic in Rochester (Minnesota) in the journal Circulation. They studied dogs with diastolic heart failure, a condition in which the heart chamber does not sufficiently fill with blood. The scientists showed that sildenafil makes stiffened cardiac walls more elastic again. The drug activates an enzyme that causes the giant protein titin in the myocardial cells to relax. "We have developed a therapy in an animal model ...

A new sensor to detect lung cancer from exhaled breath

2011-12-27

Some illnesses such as lung and stomach cancer or liver diseases which, due to the difficulty of diagnosis, have symptoms that are often confused with routine disorders. Therefore, in most cases, the disease is only detected at an advanced stage. New methods for early detection are being investigated as an urgent need.

Tecnalia, through the Interreg project Medisen, is contributing to develop biosensors capable of detecting the presence of tumour markers of lung cancer in exhaled breath. This is possible because of the changes produced within the organism of an ill person, ...

More accurate than Santa Claus

2011-12-27

Every year for Christmas, the North American Air Defence Command NORAD posts an animation on their website, in which the exact flight path of Santa Claus' sled led by reindeer Rudolf is precisely located (http://www.noradsanta.org/en/). The path of navigation satellites, however, has to be determined much more accurately than Santa's flight path, when precise ground positioning is required. GPS is the best known system of this kind, the European system Galileo is planned to be decidedly more accurate.

On 10 December, seven weeks after the start of the first two Galileo ...

Millipede border control better than ours

2011-12-27

A mysterious line where two millipede species meet has been mapped in northwest Tasmania, Australia. Both species are common in their respective ranges, but the two millipedes cross very little into each other's territory. The 'mixing zone' where they meet is about 230 km long and less than 100 m wide where carefully studied.

The mapping was done over a two-year period by Dr Bob Mesibov, who is a millipede specialist and a research associate at the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery in Launceston, Tasmania. His results have been published in the open access journal ...

Go to work on a Christmas card

2011-12-27

If all the UK's discarded wrapping paper and Christmas cards were collected and fermented, they could make enough biofuel to run a double-decker bus to the moon and back more than 20 times, according to the researchers behind a new scientific study.

The study, by scientists at Imperial College London, demonstrates that industrial quantities of waste paper could be turned into high grade biofuel, to power motor vehicles, by fermenting the paper using microorganisms. The researchers hope that biofuels made from waste paper could ultimately provide one alternative to fossil ...

UK researchers present findings from Kentucky breast cancer patients with disease relapse

2011-12-27

LEXINGTON, Ky. (Dec. 23, 2011) — The University of Kentucky Markey Cancer Center breast oncologist Dr. Suleiman Massarweh and his research team presented findings from their studies on relapse of breast cancer at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium this month.

The two studies aimed to characterize further risk factors for presentation with metastatic disease or risk of early metastatic relapse after initial therapy. Data for each study was collected from 1,089 patients at the UK Markey Cancer Center between January 2007 and May 2011.

The studies showed that patients ...

Cleveland Clinic researcher discovers genetic cause of thyroid cancer

2011-12-27

Friday, December 23, 2011, Cleveland: Cleveland Clinic researchers have discovered three genes that increase the risk of thyroid cancer, which is has the largest incidence increase in cancers among both men and women.

Research led by Charis Eng, M.D., Ph.D., Chair and founding Director of the Genomic Medicine Institute of Cleveland Clinic's Lerner Research Institute, included nearly 3,000 patients with Cowden syndrome (CS) or CS-like disease, which is related to an increased risk of breast and thyroid cancer.

Mutations in the PTEN gene are the foundation of Cowden ...

What are emotion expressions for?

2011-12-27

That cartoon scary face – wide eyes, ready to run – may have helped our primate ancestors survive in a dangerous wild, according to the authors of an article published in Current Directions in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science. The authors present a way that fear and other facial expressions might have evolved and then come to signal a person's feelings to the people around him.

The basic idea, according to Azim F. Shariff of the University of Oregon, is that the specific facial expressions associated with each particular emotion ...

Pions don't want to decay into faster-than-light neutrinos, study finds

2011-12-27

When an international collaboration of physicists came up with a result that punched a hole in Einstein's theory of special relativity and couldn't find any mistakes in their work, they asked the world to take a second look at their experiment.

Responding to the call was Ramanath Cowsik, PhD, professor of physics in Arts & Sciences and director of the McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.

Online and in the December 24 issue of Physical Review Letters, Cowsik and his collaborators put their finger on what appears to be an insurmountable ...