(Press-News.org) Recent studies have noticed a strong positive correlation between the concentration of nitrogen in forests and infrared reflectance measured from aircraft and satellites. Some scientists have suggested this demonstrates a previously overlooked role for nitrogen in regulating the earth's climate system.

However, a new paper in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shows that the apparent relationship between leaves' nitrogen levels and infrared reflection is spurious and it is in fact the structure of forest canopies (the spatial arrangement of the leaves) that determines their ability to reflect infrared light.

The authors, including Professor Philip Lewis and Dr Mathias Disney (UCL Geography), show that the richer in nitrogen individual leaves are the worse at reflecting infrared radiation they become. However, the complex arrangements of trees with radically different arrangements of leaves within a forest can act to mask this effect, making it appear as if higher levels of leaf nitrogen are leading to increased infrared reflection.

Dr Disney said: "It is impossible to understand how forests reflect infrared without taking into account the arrangement of different types of leaf clumps, such as shoots and crowns, which make up the canopy, as well as the internal structure of the leaves.

"This paper proposes a way to account for structure when measuring canopy infrared reflectance. We hope it will improve our ability to measure forest biochemistry from satellites, allowing us to better quantify forests' current state and how they are responding to climate change."

### END

Canopy structure more important to climate than leaf nitrogen levels, study claims

Claims that forest leaves rich in nitrogen may aid in reflecting infrared radiation -- helping cool the atmosphere -- have been challenged by new research that shows that the structure of tree canopies is a more important factor in infrared reflection

2012-12-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Emigration of children to urban areas can protect parents against depression

2012-12-04

Parents whose children move far away from home are less likely to become depressed than parents with children living nearby, according to a new study of rural districts in Thailand. The study, led by scientists at King's College London, suggests that children who migrate to urban areas are more likely to financially support their parents, which may be a factor for lower levels of depression.

Dr Melanie Abas, lead author from the Institute of Psychiatry at King's said: 'Parents whose children had all left the district were half as likely to be depressed as parents who ...

American Society of Clinical Oncology issues annual report on state of clinical cancer science

2012-12-04

ALEXANDRIA, Va. — The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has just released its annual report on the top cancer advances of the year. Clinical Cancer Advances 2012: ASCO's Annual Report on Progress Against Cancer, highlights major achievements in precision medicine, cancer screening and overcoming treatment resistance.

"Consistent, significant achievements are being made in oncology care with novel therapeutics, even in malignancies that have previously had few treatment options, as well as defining factors that will predict for response to treatment. ASCO's ...

Plant organ development breakthrough

2012-12-04

Stanford, CA — Plants grow upward from a tip of undifferentiated tissue called the shoot apical meristem. As the tip extends, stem cells at the center of the meristem divide and increase in numbers. But the cells on the periphery differentiate to form plant organs, such as leaves and flowers. In between these two layers, a group of boundary cells go into a quiescent state and form a barrier that not only separates stem cells from differentiating cells, but eventually forms the borders that separate the plant's organs.

Because each plant's form and shape is determined ...

Russian Far East holds seismic hazards that could threaten Pacific Basin

2012-12-04

For decades, a source of powerful earthquakes and volcanic activity on the Pacific Rim was shrouded in secrecy, as the Soviet government kept outsiders away from what is now referred to as the Russian Far East.

But research in the last 20 years has shown that the Kamchatka Peninsula and Kuril Islands are a seismic and volcanic hotbed, with a potential to trigger tsunamis that pose a risk to the rest of the Pacific Basin.

A magnitude 9 earthquake in that region in 1952 caused significant damage elsewhere on the Pacific Rim, and even less-powerful quakes have had effects ...

Study spells out hat trick for making hockey safer

2012-12-04

TORONTO, Dec. 3, 2012—Mandatory rules such as restricting body checking can limit aggression and reduce injuries in ice hockey, making the game safer for young people, a new study has found.

Rule changes could be incorporated into existing programs that reward sportsmanship and combined with educational and other strategies to reduce hockey injuries, according to researchers at St. Michael's Hospital.

The need to address the issue is critical, said Dr. Michael Cusimano, a neurosurgeon. Brain injuries such as concussions frequently result from legal or illegal aggressive ...

Children with autism arrive at emergency room for psychiatric crisis 9 times more than peers

2012-12-04

BALTIMORE, Md. (December 3, 2012) – In the first study to compare mental health-related emergency department (ED) visits between children with and without autism spectrum disorders (ASD), researchers found that ED visits are nine times more likely to be for psychiatric reasons if a child has an ASD diagnosis. Published in the journal Pediatric Emergency Care (Epub ahead of print), the study found externalizing symptoms, such as severe behaviors tied to aggression, were the leading cause of ED visits among children with ASD. Importantly, the likelihood of a psychiatric ED ...

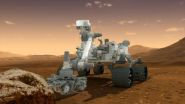

Curiosity shakes, bakes, and tastes Mars with SAM

2012-12-04

NASA's Curiosity rover analyzed its first solid sample of Mars in Nov. with a variety of instruments, including the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) instrument suite. Developed at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., SAM is a portable chemistry lab tucked inside the Curiosity rover. SAM examines the chemistry of samples it ingests, checking particularly for chemistry relevant to whether an environment can support or could have supported life.

The sample of Martian soil came from the patch of windblown material called "Rocknest," which had provided a sample ...

Alzheimer's researcher reveals a protein's dual destructiveness – and therapeutic potential

2012-12-04

A scientist at the University of British Columbia and Vancouver Coastal Health has identified the molecule that controls a scissor-like protein responsible for the production of plaques – the telltale sign of Alzheimer's disease (AD).

The molecule, known as GSK3-beta, activates a gene that creates a protein, called BACE1. When BACE1 cuts another protein, called APP, the resulting fragment – known as amyloid beta – forms tiny fibers that clump together into plaques in the brain, eventually killing neural cells.

Using an animal model, Dr. Weihong Song, Canada Research ...

Search for life suggests solar systems more habitable than ours

2012-12-04

SAN FRANCISCO—Scattered around the Milky Way are stars that resemble our own sun—but a new study is finding that any planets orbiting those stars may very well be hotter and more dynamic than Earth.

That's because the interiors of any terrestrial planets in these systems are likely warmer than Earth—up to 25 percent warmer, which would make them more geologically active and more likely to retain enough liquid water to support life, at least in its microbial form.

The preliminary finding comes from geologists and astronomers at Ohio State University who have teamed up ...

DNA analysis of microbes in a fracking site yields surprises

2012-12-04

SAN FRANCISCO—Researchers have made a genetic analysis of the microbes living deep inside a deposit of Marcellus Shale at a hydraulic fracturing, or "fracking," site, and uncovered some surprises.

They expected to find many tough microbes suited to extreme environments, such as those that derive from archaea, a domain of single-celled species sometimes found in high-salt environments, volcanoes, or hot springs. Instead, they found very few genetic biomarkers for archaea, and many more for species that derive from bacteria.

They also found that the populations of microbes ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Tools to glimpse how “helicity” impacts matter and light

Smartphone app can help men last longer in bed

Longest recorded journey of a juvenile fisher to find new forest home

Indiana signs landmark education law to advance data science in schools

A new RNA therapy could help the heart repair itself

The dehumanization effect: New PSU research examines how abusive supervision impacts employee agency and burnout

New gel-based system allows bacteria to act as bioelectrical sensors

The power of photonics

From pioneer to leader: Alex Zhavoronkov chairs precision aging discussion and presents Luminary Award to OpenAI president at PMWC 2026

Bursting cancer-seeking microbubbles to deliver deadly drugs

In a South Carolina swamp, researchers uncover secrets of firefly synchrony

American Meteorological Society and partners issue statement on public availability of scientific evidence on climate change

How far will seniors go for a doctor visit? Often much farther than expected

Selfish sperm hijack genetic gatekeeper to kill healthy rivals

Excessive smartphone use associated with symptoms of eating disorder and body dissatisfaction in young people

‘Just-shoring’ puts justice at the center of critical minerals policy

A new method produces CAR-T cells to keep fighting disease longer

Scientists confirm existence of molecule long believed to occur in oxidation

The ghosts we see

ACC/AHA issue updated guideline for managing lipids, cholesterol

Targeting two flu proteins sharply reduces airborne spread

Heavy water expands energy potential of carbon nanotube yarns

AMS Science Preview: Mississippi River, ocean carbon storage, gender and floods

High-altitude survival gene may help reverse nerve damage

Spatially decoupling active-sites strategy proposed for efficient methanol synthesis from carbon dioxide

Recovery experiences of older adults and their caregivers after major elective noncardiac surgery

Geographic accessibility of deceased organ donor care units

How materials informatics aids photocatalyst design for hydrogen production

BSO recapitulates anti-obesity effects of sulfur amino acid restriction without bone loss

Chinese Neurosurgical Journal reports faster robot-assisted brain angiography

[Press-News.org] Canopy structure more important to climate than leaf nitrogen levels, study claimsClaims that forest leaves rich in nitrogen may aid in reflecting infrared radiation -- helping cool the atmosphere -- have been challenged by new research that shows that the structure of tree canopies is a more important factor in infrared reflection