(Press-News.org) BOSTON -- In biology, as in real estate, location matters. Working copies of active genes -- called messenger RNAs or mRNAs -- are positioned strategically throughout living tissues, and their location often helps regulate how cells and tissues grow and develop. But to analyze many mRNAs simultaneously, scientists have had to grind cells to a pulp, which left them no good way to pinpoint where those mRNAs sat within the cell.

Now a team at the Wyss Institute of Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University and Harvard Medical School, in collaboration with the Allen Institute for Brain Science, has developed a new method that allows scientists to pinpoint thousands of mRNAs and other types of RNAs at once in intact cells -- all while determining the sequence of letters, or bases, that identify them and reveal what they do.

The method, called fluorescent in situ RNA sequencing (FISSEQ), could lead to earlier cancer diagnosis by revealing molecular changes that drive cancer in seemingly healthy tissue. It could track cancer mutations and how they respond to modern targeted therapies, and uncover targets for safer and more effective ones.

The method could also help biologists understand how tissues change subtly during embryonic development -- and even help map the maze of neurons that wire the human brain. The researchers reported the method in today's online edition of Science.

"By looking comprehensively at gene expression within cells, we can now spot numerous important differences in complex tissues like the brain that are invisible today," said George Church, Ph.D., a Core Faculty member at the Wyss Institute and Professor of Genetics at Harvard Medical School. "This will help us understand like never before how tissues develop and function in health and disease."

Locking RNAs in Place

Healthy human cells typically turn on nearly half of their 20,000 genes at any given time, and they choose those genes carefully to produce the desired cellular responses. Moreover, cells can dial gene expression up or down, adjusting to produce anywhere from a few working copies of a gene to several thousand.

VIDEO:

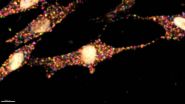

As "letters, " or bases, are added to RNAs throughout the cell during fluorescent in situ sequencing, the RNAs flash a specific color that indicates which base has been added (0:00-0:05...

Click here for more information.

But simultaneously pinpointing the cellular location of all those mRNAs is a tall order.

Church and Je Hyuk Lee, Ph.D., a Research Fellow at the Wyss Institute and Harvard Medical School, were up for the challenge. Moreover, they wanted to simultaneously determine the sequence of those RNAs, which identifies them and often reveals their function.

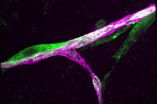

Lee and his colleagues first treated the tissue chemically to fix the cell's thousands of RNAs in place. Then they used enzymes to copy those RNAs into DNA replicas, and copy those replicas many times to create a tiny ball of replica DNA fixed to the same spot.

They managed to fix and replicate thousands of the cell's RNAs at once -- but then became a victim of their own success. The RNAs were so tightly packed inside the cell that even a tricked-out microscope and camera could not distinguish the flashing lights of one individual ball of replica DNA from those of its neighbors.

A new way to image RNA

To solve that problem, the researchers pioneered an unconventional method to visualize tiny objects inside cells. It works like an urban postal system. If a postmaster tried to identify each home in her city by color, she would quickly run out of colors as new homes were built, resulting in undelivered mail. Instead, postmasters keep track of each home by assigning it a unique address.

VIDEO:

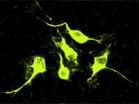

Fluorescent in situ sequencing allows scientists to simultaneously determine the base sequence and location of many RNAs in a single cell or across a landscape of cells.

Click here for more information.

The researchers realized they could assign each RNA in the cell a unique address: the sequence of "letters," or bases, in the RNA molecule itself. And they figured they could read the address using methods akin to next-generation DNA sequencing, a set of high-speed genome sequencing methods Church helped develop in the early 2000s.

In next-gen sequencing, scientists grind up tissue, extract its DNA, break the DNA into pieces, then dilute those pieces enough so that each piece of DNA sticks to a separate spot on a glass slide. They use enzymes and four different fluorescent dyes -- one each for each of the four "letters," or bases -- to make the DNA flash a sequence of colors that reveals its sequence.

By analogy, the scientists sought to fix RNA in place in the cell, make a tiny ball with many matching DNA replicas of each RNA, then adapt next-gen DNA sequencing so it worked in fixed cells. The four flashing colors would reveal the base sequence of each replica DNA, which would tell them the base sequence of the matching RNA from which it was derived. And those sequences would in theory provide an unlimited number of unique addresses – one for each of the original RNAs.

The scientists struggled at first to visualize the flashing lights of individual balls of replica DNA from a distance where the whole landscape of the tissue remained in view.

They succeeded by selectively turning on just a fraction of those flashing dots at any given time, so they could distinguish single balls of replica DNA flashing across the cellular landscape.

The strategy would only work, however, if they could actually read enough of the base sequence to provide a unique address. At first they could not determine more than six bases in the replica DNA, which did not provide enough unique addresses to identify individual genes in the human genome. That's when Evan Daugharthy, a graduate student at Harvard Medical School, stepped in.

FISSEQ at Work

Daugharthy first devised an algorithm to locate the sequence of the replica DNA with the known sequence of genes in the human genome. Flashing lights that did not correspond to a real gene were erased from the image.

Then Daugharthy hacked a commercial DNA sequencing kit, which enabled the team to sequence 30 bases, more than enough to provide each replica DNA with a unique address. In this way the team could create a composite image representing the sequence, and location, of RNA corresponding to every gene in the human genome.

Lee, Daugharthy and their colleagues then tested the method to detect the genes skin cells turn on as they multiply and migrate to heal a simulated wound in a petri dish. Cells growing into the wound had 12 genes that were activated much more or much less than nearby cells sitting idly on the sidelines. Similar experiments could identify new markers of diseased tissue or new targets for targeted molecular therapies.

"What George's team has accomplished is a technological tour de force," said Wyss Institute Founding Director Don Ingber, M.D., Ph.D. "By spotting incredibly subtle but incredibly important changes in gene expression and precisely defining their position inside the cell, they have helped open the door to a new age of cellular diagnostics."

INFORMATION:

The work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Allen Institute for Brain Science and the Wyss Institute.

PRESS CONTACT

Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University

Dan Ferber

dan.ferber@wyss.harvard.edu

+1 617-432-1547

IMAGE AND VIDEOS AVAILABLE

About the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University

The Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University uses Nature's design principles to develop bioinspired materials and devices that will transform medicine and create a more sustainable world. Working as an alliance among Harvard's Schools of Medicine, Engineering, and Arts & Sciences, and in partnership with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston Children's Hospital, Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Massachusetts General Hospital, the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, Boston University, Tufts University, and Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, the Institute crosses disciplinary and institutional barriers to engage in high-risk research that leads to transformative technological breakthroughs. By emulating Nature's principles, Wyss researchers are developing innovative new engineering solutions for healthcare, energy, architecture, robotics, and manufacturing. These technologies are translated into commercial products and therapies through collaborations with clinical investigators, corporate alliances, and new start-ups. The Wyss Institute recently won the prestigious World Technology Network award for innovation in biotechnology.

About Harvard Medical School

Harvard Medical School has more than 7,500 full-time faculty working in 11 academic departments located at the School's Boston campus or in one of 47 hospital-based clinical departments at 16 Harvard-affiliated teaching hospitals and research institutes. Those affiliates include Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Cambridge Health Alliance, Boston Children's Hospital, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, Hebrew SeniorLife, Joslin Diabetes Center, Judge Baker Children's Center, Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Massachusetts General Hospital, McLean Hospital, Mount Auburn Hospital, Schepens Eye Research Institute, Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital and VA Boston Healthcare System.

A bird's eye view of cellular RNAs

New method identifies working copies of genes in human cells; could help diagnose sick tissues early

2014-02-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists uncover trigger for most common form of intellectual disability and autism

2014-02-27

NEW YORK (February 27, 2014) -- A new study led by Weill Cornell Medical College scientists shows that the most common genetic form of mental retardation and autism occurs because of a mechanism that shuts off the gene associated with the disease. The findings, published today in Science, also show that a drug that blocks this silencing mechanism can prevent fragile X syndrome – suggesting similar therapy is possible for 20 other diseases that range from mental retardation to multisystem failure.

Fragile X syndrome occurs mostly in boys, causing intellectual disability ...

CU-led study says Bering Land Bridge a long-term refuge for early Americans

2014-02-27

A new study led by the University of Colorado Boulder bolsters the theory that the first Americans, who are believed to have come over from northeast Asia during the last ice age, may have been isolated on the Bering Land Bridge for thousands of years before spreading throughout the Americas.

The theory, now known as the "Beringia Standstill," was first proposed in 1997 by two Latin American geneticists and refined in 2007 by a team led by the University of Tartu in Estonia that sampled mitrochondrial DNA from more than 600 Native Americans. The researchers found that ...

Fossils offer new clues into Native American's 'journey' and how they survived the last Ice Age

2014-02-27

Researchers have discovered how Native Americans may have survived the last Ice Age after splitting from their Asian relatives 25,000 years ago.

Academics at Royal Holloway, University of London, and the Universities of Colorado and Utah have analysed fossils which revealed that the ancestors of Native Americans may have set up home in a region between Siberia and Alaska which contained woody plants that they could use to make fires. The discovery breaks new ground as until now no-one had any idea of where the native Americans spent the next 10,000 years before they appeared ...

Researchers reveal the dual role of brain glycogen

2014-02-27

In 2007, in an article published in Nature Neuroscience, scientists at the Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB Barcelona) headed by Joan Guinovart, an authority on glycogen metabolism, reported that in Lafora Disease (LD), a rare and fatal neurodegenerative condition that affects adolescents, neurons die as a result of the accumulation of glycogen—chains of glucose. They went on to propose that this accumulation is the root cause of this disease.

The breakthrough of this paper was two-sided: first, the researchers established a possible cause of LD and therefore ...

UCSB study reveals evolution at work

2014-02-27

New research by UC Santa Barbara's Kenneth S. Kosik, Harriman Professor of Neuroscience, reveals some very unique evolutionary innovations in the primate brain.

In a study published online today in the journal Neuron, Kosik and colleagues describe the role of microRNAs — so named because they contain only 22 nucleotides — in a portion of the brain called the outer subventricular zone (OSVZ). These microRNAs belong to a special category of noncoding genes, which prevent the formation of proteins.

"It's microRNAs that provide the wiring diagram, dictating which genes ...

Big step for next-generation fuel cells and electrolyzers

2014-02-27

A big step in the development of next-generation fuel cells and water-alkali electrolyzers has been achieved with the discovery of a new class of bimetallic nanocatalysts that are an order of magnitude higher in activity than the target set by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) for 2017. The new catalysts, hollow polyhedral nanoframes of platinum and nickel, feature a three-dimensional catalytic surface activity that makes them significantly more efficient and far less expensive than the best platinum catalysts used in today's fuel cells and alkaline electrolyzers. This ...

Fossilized human feces from 14th century contain antibiotic resistance genes

2014-02-27

A team of French investigators has discovered viruses containing genes for antibiotic resistance in a fossilized fecal sample from 14th century Belgium, long before antibiotics were used in medicine. They publish their findings ahead of print in the journal Applied and Environmental Microbiology.

"This is the first paper to analyze an ancient DNA viral metagenome," says Rebecca Vega Thurber of Oregon State University, Corvallis, who was not involved in the research.

The viruses in the fecal sample are phages, which are viruses that infect bacteria, rather than infecting ...

Physicians' stethoscopes more contaminated than palms of their hands

2014-02-27

VIDEO:

A comparative analysis shows that stethoscope diaphragms are more contaminated than the physician's own thenar eminence (group of muscles in the palm of the hand) following a physical examination.

Click here for more information.

Rochester, MN, February 27, 2014 – Although healthcare workers' hands are the main source of bacterial transmission in hospitals, physicians' stethoscopes appear to play a role. To explore this question, investigators at the University of ...

Study reveals mechanisms cancer cells use to establish metastatic brain tumors

2014-02-27

NEW YORK, NY, February 27, 2014 — New research from Memorial Sloan Kettering provides fresh insight into the biologic mechanisms that individual cancer cells use to metastasize to the brain. Published in the February 27 issue of Cell, the study found that tumor cells that reach the brain — and successfully grow into new tumors — hug capillaries and express specific proteins that overcome the brain's natural defense against metastatic invasion.

Metastasis, the process that allows some cancer cells to break off from their tumor of origin and take root in a different tissue, ...

Methane leaks from palm oil wastewater are a climate concern, CU-Boulder study says

2014-02-27

In recent years, palm oil production has come under fire from environmentalists concerned about the deforestation of land in the tropics to make way for new palm plantations. Now there is a new reason to be concerned about palm oil's environmental impact, according to researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder.

An analysis published Feb. 26 in the journal Nature Climate Change shows that the wastewater produced during the processing of palm oil is a significant source of heat-trapping methane in the atmosphere. But the researchers also present a possible solution: ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

[Press-News.org] A bird's eye view of cellular RNAsNew method identifies working copies of genes in human cells; could help diagnose sick tissues early