(Press-News.org) Everybody has experienced this: You aren't careful for just one moment and suddenly you run into the edge of a table. At first, it hurts. A little later, a bruise starts to appear. What falls into the category of "nothing bad, but aggravating" in the case of a table, takes on a new dimension when the colliding partner is a robot, because such a collision can injure humans seriously. That is why these mechanical assistants usually still work behind protective barriers. Since some applications require humans and robots to work hand-in-hand, though, their cooperation has become one of the foci of robotics research worldwide. Where exactly does the threshold between harmless contact and an injury lie, though?

Minor Impacts, Major Findings

How much force does it take for an impact to leave a bruise on different body parts? When do humans suffer permanent injuries? Nobody has been able to say precisely. There are no extensive studies on the subject. Collision geometry, i.e. the geometry of the colliding objects, also has great influence on the severity of injuries from a collision. Researchers at the Fraunhofer Institute for Factory Operation and Automation IFF in Magdeburg are exploring wholly uncharted terrain with a new study: They are systematically studying the thresholds of biomechanical loads resulting from collisions between robots and humans.

The researchers' approach: They load a pendulum with different weights, pull it back and allow it to hit against different body parts of the participants of the study. A special sensor film on the pendulum's impact face measures the pressure distribution upon impact. A force sensor, also located on the impact face, measures the characteristics of the contact force, the maximum force applied and the action time. "This enables us to measure every relevant parameter such as force, pressure distribution, impact velocity, momentum and energy," says Dr. Norbert Elkmann, business unit manager at the Fraunhofer IFF.

On the medical side, the study is being supported by the Department of Forensic Medicine, the Dermatology Clinic, the Trauma Surgery Clinic and the Department of Neuroradiology of Otto von Guericke University Hospital Magdeburg. The Otto von Guericke University Ethics Commission has given the study its approval. Test discontinuation criteria are incipient swelling or bruising or when subjects reach their pain threshold.

In the pilot phase, the researchers first developed the measurement system and refined the methodology – together with medical professionals. They are now producing the first findings with several subjects in a preliminary stage. Afterward, the researchers will decide how many participants will be needed in the study to obtain representative results. The researchers from the Fraunhofer IFF will present their initial findings at the International Conference on Robotics and Automation ICRA in Hong Kong in June of 2014.

Their findings will also benefit criminal investigative agencies and medical examiners: Whenever victims of violent crimes come to officials or physicians and their subdermal hematomas are hard to see, the intensity of the trauma can hardly be determined. Victims as well as physicians would be helped greatly if medical examiners were able to fall back on pertinent studies.

The study will also have a value for the consumer sector: After all, robots are now commonplace in many households. They vacuum, mop the floor or mow the lawn. Robots will likely take over even many more jobs in households in the future but only if humans are safely protected against injuries from collisions with them. The Fraunhofer IFF is obtaining fundamental data in its study, the results of which will be incorporated in international standards.

INFORMATION: END

Collisions with robots -- without risk of injury

2014-07-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Preterm babies more likely to survive in larger newborn care units

2014-07-08

Premature newborns are 32% less likely to die if they are admitted to high volume neonatal units rather than low volume, according to new research.

The study, led by the University of Warwick and published in BMJ Open, analysed data from 165 neonatal units across the UK. It found babies born at less than 33 weeks gestation were 32% less likely to die if they were admitted to high volume units, compared to low volume.

For babies born at less than 27 weeks the effect was greater, with the odds of dying almost halved when they were admitted to high volume units, compared ...

New research finds working memory is the key to early academic achievement

2014-07-08

Working memory in children is linked strongly to reading and academic achievement, a new study from the University of Luxembourg and partner Universities from Brazil* has shown. Moreover, this finding holds true regardless of socio-economic status. This suggests that children with learning difficulties might benefit from teaching methods that prevent working memory overload. The study was published recently in the scientific journal "Frontiers in Psychology".

The study was conducted in Brazil on 106 children between 6 and 8 from a range of social backgrounds, with half ...

Sandalwood scent facilitates wound healing and skin regeneration

2014-07-08

Skin cells possess an olfactory receptor for sandalwood scent, as researchers at the Ruhr-Universität Bochum have discovered. Their data indicate that the cell proliferation increases and wound healing improves if those receptors are activated. This mechanism constitutes a possible starting point for new drugs and cosmetics. The team headed by Dr Daniela Busse and Prof Dr Dr Dr med habil Hanns Hatt from the Department for Cellphysiology published their report in the "Journal of Investigative Dermatology".

The nose is not the only place where olfactory receptors occur

Humans ...

Treatment-resistant hypertension requires proper diagnosis

2014-07-08

High blood pressure—also known as hypertension—is widespread, but treatment often fails. One in five people with hypertension does not respond to therapy. This is frequently due to inadequate diagnosis, as Franz Weber and Manfred Anlauf point out in the current issue of Deutsches Ärzteblatt International (Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014; 111: 425–31).

If a patient's blood pressure is not controlled by treatment, this can be due to a number of reasons. Often it is the medication the patient is on. Some patients may be taking other medicines – in addition to their antihypertensive ...

When faced with some sugars, bacteria can be picky eaters

2014-07-08

Researchers from North Carolina State University and the University of Minnesota have found for the first time that genetically identical strains of bacteria can respond very differently to the presence of sugars and other organic molecules in the environment, with some individual bacteria devouring the sugars and others ignoring it.

"This highlights the complexity of bacterial behaviors and their response to environmental conditions, and how much we still need to learn," says Dr. Chase Beisel, an assistant professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at NC State ...

A possible pathway for inhibiting liver and colon cancer is found

2014-07-08

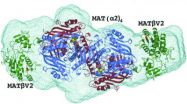

A group of scientists from Spain, the UK and the United States has revealed the structure of a protein complex involved in liver and colon cancers. Both of these types of cancer are of significant social and clinical relevance as in 2012 alone, liver cancer was responsible for the second highest mortality rate worldwide, with colon cancer appearing third in the list.

The international team from CIC bioGUNE, the University of Liverpool and the US research centre USC-UCLA has successfully unravelled the mechanism by which two proteins, MATα2 and MATβ, bind to ...

KAIST develops TransWall, a transparent touchable display wall

2014-07-08

Daejeon, Republic of Korea, July 8, 2014 – At a busy shopping mall, shoppers walk by store windows to find attractive items to purchase. Through the windows, shoppers can see the products displayed, but may have a hard time imagining doing something beyond just looking, such as touching the displayed items or communicating with sales assistants inside the store. With TransWall, however, window shopping could become more fun and real than ever before.

Woohun Lee, a professor of Industrial Design at KAIST, and his research team have recently developed TransWall, a two-sided, ...

Travel campaign fuels $1B rise in hospitality industry

2014-07-08

EAST LANSING, Mich. --- The Obama administration's controversial travel-promotion program has generated a roughly $1 billion increase in the value of the hospitality industry and stands to benefit the U.S. economy in the long run.

So finds the first scientific evidence, from a Michigan State University-led study, showing a positive economic impact of the Travel Promotion Act. Congress is currently reviewing whether to extend the law, which went into effect in March 2010.

"We found positive stock market reactions related to the passage of the act and therefore agree ...

Low doses of arsenic cause cancer in male mice

2014-07-08

Mice exposed to low doses of arsenic in drinking water, similar to what some people might consume, developed lung cancer, researchers at the National Institutes of Health have found.

Arsenic levels in public drinking water cannot exceed 10 parts per billion (ppb), which is the standard set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. However, there are no established standards for private wells, from which millions of people get their drinking water.

In this study, the concentrations given to the mice in their drinking water were 50 parts per billion (ppb), 500 ppb, ...

Recalled yogurt contained highly pathogenic mold

2014-07-08

DURHAM, N.C. -- Samples isolated from Chobani yogurt that was voluntarily recalled in September 2013 have been found to contain the most virulent form of a fungus called Mucor circinelloides, which is associated with infections in immune-compromised people.

The study by Duke University scientists shows that this strain of the fungus can survive in a mouse and be found in its feces as many as 10 days after ingestion.

In August and September 2013, more than 200 consumers of contaminated Chobani Greek Yogurt became ill with vomiting, nausea and diarrhea. The U.S. Food ...