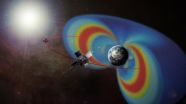

(Press-News.org) One of the great, unanswered questions for space weather scientists is just what creates two gigantic donuts of radiation surrounding Earth, called the Van Allen radiation belts. Recent data from the Van Allen Probes -- two nearly identical spacecraft that launched in 2012 -- address this question.

The inner Van Allen radiation belt is fairly stable, but the outer one changes shape, size and composition in ways that scientists don't yet perfectly understand. Some of the particles within this belt zoom along at close to light speed, but just what accelerates these particles up to such velocities? Recent data from the Van Allen Probes suggests that it is a two-fold process: One mechanism gives the particles an initial boost and then a kind of electromagnetic wave called Whistlers does the final job to kick them up to such intense speeds.

"It is important to understand how this process happens," said Forrest Mozer, a space scientist at the University of California in Berkeley and the first author of the paper on these results that appeared online in Physical Review Letters on July 15, 2014, in conjunction with the July 18 print edition. "Not only do we think a similar process happens on the sun and around other planets, but these fast particles can damage the electronics in spacecraft and affect astronauts in space."

Over the last few decades, numerous theories about where these extremely energetic particles come from have been developed. They have largely fallen into two different possibilities. The first theory is that the particles drift in from much further out, some 400,000 miles or more, gathering energy along the way. The second theory is that some mechanism speeds up particles already inhabiting that area of space. After two years in space, the Van Allen Probes data has largely pointed to the latter.

Additionally, it has been shown that once particles attain reasonably large energies of 100 keV, they are moving at speeds in synch with giant electromagnetic waves that can speed the particles up even more – the same way a well-timed push on a swing can keep it moving higher and higher.

"This paper incorporates the Whistler waves theory previously embraced," said Shri Kanekal, the deputy mission scientist for the Van Allen Probes at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. "But it provides a new explanation for how the particles get their initial push of energy."

This first mechanism is based on something called time domain structures, which Mozer and his colleagues have identified previously in the belts. They are very short duration pulses of electric field that run parallel to the magnetic fields that thread through the radiation belts. These magnetic field lines guide the movement of all the charged particles in the belts: The particles move along and gyrate around the lines as if they were tracing out the shape of a spring. During this early phase, the electric pulses push the particles faster forward in the direction parallel to the magnetic fields. This mechanism can increase the energies somewhat – though not as high as traditionally thought to be needed for the Whistler waves to have any effect. However, Mozer and his team showed, through both data from the Van Allen Probes and from simulations, that Whistlers can indeed affect particles at these lower energies.

Together the one-two punch is a mechanism that can effectively accelerate particles up to the intense speeds, which have for so long mysteriously appeared in the Van Allen belts.

"The Van Allen Probes have been able to monitor this acceleration process better than any other spacecraft because it was designed and placed in a special orbit for that purpose," said Mozer. "The mission has provided the first really strong confirmation of what's happening. This is the first time we can truly explain how the electrons are accelerated up to nearly the speed of light."

Such knowledge helps with the job of understanding the belts well enough to protect nearby spacecraft and astronauts.

INFORMATION:

The Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, built and operates the Van Allen Probes for NASA's Science Mission Directorate. The mission is the second mission in NASA's Living With a Star program, managed by NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

For more information about NASA's Van Allen Probes mission, visit:

http://www.nasa.gov/vanallenprobes

NASA's Van Allen Probes show how to accelerate electrons

2014-07-15

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NOAA's GOES-R satellite Magnetometer ready for spacecraft integration

2014-07-15

The Magnetometer instrument that will fly on NOAA's GOES-R satellite when it is launched in early 2016 has completed the development and testing phase and is ready to be integrated with the spacecraft.

The Magnetometer will monitor magnetic field variations around the Earth and enable forecasters at NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center to better predict the consequences of geomagnetic storms. These storms pose a threat to orbiting spacecraft and human spaceflight. In addition, the measurements taken by the Magnetometer will aid in providing alerts and warnings to power ...

For bees and flowers, tongue size matters

2014-07-15

For bees and the flowers they pollinate, a compatible tongue length is essential to a successful relationship. Some bees and plants are very closely matched, with bee tongue sized to the flower depth. Other bee species are generalists, flitting among flower species to drink nectar and collect pollen from a diverse variety of plants. Data on tongue lengths can help ecologists understand and predict the behavior, resilience and invasiveness of bee populations.

But bee tongues are hard to measure. The scarcity of reliable lingual datasets has held back research, so Ignasi ...

Study finds why some firms are 'named and shamed' by activists

2014-07-15

COLUMBUS, Ohio – A new study of the anti-sweatshop campaigns of the 1990s reveals which companies are most likely to become targets of anti-corporate activists.

Researchers found that companies tended to attract the attention of labor activists if they were large, had prominent brand images, or had good corporate reputations. When combined, these factors were especially important.

"Companies that had all of these characteristics were nearly guaranteed to be a target of activism," said Tim Bartley, lead author of the study and associate professor of sociology at The ...

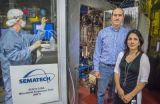

Fundamental chemistry findings could help extend Moore's Law

2014-07-15

Over the years, computer chips have gotten smaller thanks to advances in materials science and manufacturing technologies. This march of progress, the doubling of transistors on a microprocessor roughly every two years, is called Moore's Law. But there's one component of the chip-making process in need of an overhaul if Moore's law is to continue: the chemical mixture called photoresist. Similar to film used in photography, photoresist, also just called resist, is used to lay down the patterns of ever-shrinking lines and features on a chip.

Now, in a bid to continue decreasing ...

Study: Body Dysmorphic Disorder patients have higher risk of personal and appearance-based rejection sensitivity

2014-07-15

PROVIDENCE, R.I. – In a recent study, researchers at Rhode Island Hospital found that fear of being rejected because of one's appearance, as well as rejection sensitivity to general interpersonal situations, were significantly elevated in individuals with Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD). These fears, referred to as personal rejection sensitivity and appearance-based rejection sensitivity, can lead to diminished quality of life and poorer mental and overall health. BDD is a common, often severe, and under-recognized body image disorder that affects an estimated 1.7 to 2.4 ...

Prostate cancer in young men -- More frequent and more aggressive?

2014-07-15

ANN ARBOR, Mich. -- The number of younger men diagnosed with prostate cancer has increased nearly 6-fold in the last 20 years, and the disease is more likely to be aggressive in these younger men, according to a new analysis from researchers at the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Typically, prostate cancer occurs more frequently as men age into their 70s or 80s. Many prostate cancers are slow-growing and many older men diagnosed with early stage prostate cancer will end up dying from causes other than prostate cancer.

But, the researchers found, ...

Rollout strategy for diagnostic test in India may impact TB

2014-07-15

Xpert MTB/RIF, a recently implemented tuberculosis (TB) test, has the potential to control the TB epidemic in India, but only if the current, narrow, implementation strategy is replaced by a more ambitious one that is better funded, also includes the private sector, and better referral networks are developed between public and private sectors, according to new research published in this week's PLOS Medicine. The study by David Dowdy, from Johns Hopkins University, United States, and colleagues is a mathematical model that suggests alternative strategies that include engagement ...

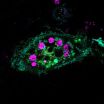

Molecular 'eat now' signal makes cells devour dying neighbors

2014-07-15

A team of researchers has devised a Pac-Man-style power pellet that gets normally mild-mannered cells to gobble up their undesirable neighbors. The development may point the way to therapies that enlist patients' own cells to better fend off infection and even cancer, the researchers say.

A description of the work will be published July 15 in the journal Science Signaling.

"Our goal is to build artificial cells programmed to eat up dangerous junk in the body, which could be anything from bacteria to the amyloid-beta plaques that cause Alzheimer's to the body's own ...

Neurons, brain cancer cells require the same little-known protein for long-term survival

2014-07-15

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – Researchers at the UNC School of Medicine have discovered that the protein PARC/CUL9 helps neurons and brain cancer cells override the biochemical mechanisms that lead to cell death in most other cells. In neurons, long-term survival allows for proper brain function as we age. In brain cancer cells, though, long-term survival contributes to tumor growth and the spread of the disease.

These results, published in the journal Science Signaling, not only identify a previously unknown mechanism used by neurons for their much-needed survival, but show that ...

Rollout strategy is key to battling India's TB epidemic, researchers find

2014-07-15

A new study led by Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health researchers suggests that getting patients in India quickly evaluated by the right doctors can be just as effective at curbing tuberculosis (TB) as a new, highly accurate screening test.

While ideally all suspected TB cases would be evaluated with the new test, it is primarily being used only on the highest-risk populations and only in public health clinics, partly because of its cost and the complexity of the nation's health care system. This slows diagnosis of a disease that must be caught early, the ...