(Press-News.org) Adolescence is often a turbulent time, and it is marked by substantially increased rates of depressive symptoms, especially among girls. New research indicates that this gender difference may be the result of girls' greater exposure to stressful interpersonal events, making them more likely to ruminate, and contributing to their risk of depression.

The findings are published in Clinical Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

"These findings draw our focus to the important role of stress as a potential causal factor in the development of vulnerabilities to depression, particularly among girls, and could change the way that we target risk for adolescent depression," says psychology researcher and lead author on the study, Jessica Hamilton of Temple University.

"Although there is a range of other vulnerabilities that contribute to the emergence of girls' higher rates of depression during adolescence, our study highlights an important malleable pathway that explains girls' greater risk of depression."

Research has shown that cognitive vulnerabilities associated with depression, such as negative cognitive style and rumination, emerge during adolescence. Teens who tend to interpret events in negative ways (negative cognitive style) and who tend to focus on their depressed mood following such events (rumination) are at greater risk of depression.

Hamilton, a doctoral student in the Mood and Cognition Laboratory of Lauren Alloy at Temple University, hypothesized that life stressors, especially those related to adolescents' interpersonal relationships and that adolescents themselves contribute to (such as a fight with a family member or friend), would facilitate these vulnerabilities and, ultimately, increase teens' risk of depression.

The researchers examined data from 382 Caucasian and African American adolescents participating in an ongoing longitudinal study. The adolescents completed self-report measures evaluating cognitive vulnerabilities and depressive symptoms at an initial assessment, and then completed three follow-up assessments, each spaced about 7 months apart.

As expected, teens who reported higher levels of interpersonal dependent stress showed higher levels of negative cognitive style and rumination at later assessments, even after the researchers took initial levels of the cognitive vulnerabilities, depressive symptoms, and sex into account.

Girls tended to show more depressive symptoms at follow-up assessments than did boys — while boys' symptoms seemed to decline from the initial assessment to follow-up, girls' symptoms did not.

Girls also were exposed to a greater number of interpersonal dependent stressors during that time, and analyses suggest that it is this exposure to stressors that maintained girls' higher levels of rumination and, thus, their risk for depression over time.

The researchers emphasize that the link is not driven by reactivity to stress — girls were not any more reactive to the stressors that they experienced than were boys.

"Simply put, if boys and girls had been exposed to the same number of stressors, both would have been likely to develop rumination and negative cognitive styles," Hamilton explains.

Importantly, other types of stress — including interpersonal stress that is not dependent on the teen (such as a death in the family) and achievement-related stress — were not associated with later levels of rumination or negative cognitive style.

"Parents, educators, and clinicians should understand that girls' greater exposure to interpersonal stressors places them at risk for vulnerability to depression and ultimately, depression itself," says Hamilton. "Thus, finding ways to reduce exposure to these stressors or developing more effective ways of responding to these stressors may be beneficial for adolescents, especially girls."

According to Hamilton, the next step will be to figure out why girls are exposed to more interpersonal stressors:

"Is it something specific to adolescent female relationships? Is it the societal expectations for young adolescent girls or the way in which young girls are socialized that places them at risk for interpersonal stressors? These are questions to which we need to find answers!"

INFORMATION:

Co-authors on the study include Jonathan P. Stange and Lauren B. Alloy of Temple University and Lyn Y. Abramson of the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

This work was supported by NIMH Grants MH79369 and MH101168 to Lauren B. Alloy. Jonathan P. Stange was supported by National Research Service Award F31MH099761 from NIMH.

For more information about this study, please contact: Lauren B. Alloy at lalloy@temple.edu.

The article abstract is available online: http://cpx.sagepub.com/content/early/2014/09/29/2167702614545479.abstract

Clinical Psychological Science is APS's newest journal. For a copy of the article "Stress and the Development of Cognitive Vulnerabilities to Depression Explain Sex Differences in Depressive Symptoms During Adolescence" and access to other Clinical Psychological Science research findings, please contact Anna Mikulak at 202-293-9300 or amikulak@psychologicalscience.org.

Teenage girls are exposed to more stressors that increase depression risk

2014-10-08

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists identify method of eradicating harmful impacts from manufacturing process

2014-10-08

The human and environmental dangers posed by a widely used manufacturing technique could be almost eradicated thanks to research led by Plymouth University.

Fibre-reinforced polymer matrix composites are painted or sprayed onto products to provide a high-quality finish in transport applications, chemical plants, renewable energy systems and pipelines.

But that finishing process causes the vapours of a volatile organic compound – styrene, found in polyesters and vinyl-esters – to be emitted, posing potential health and wellbeing risks to the workforces involved ...

Smallest world record has 'endless possibilities' for bio-nanotechnology

2014-10-08

Scientists from the University of Leeds have taken a crucial step forward in bio-nanotechnology, a field that uses biology to develop new tools for science, technology and medicine.

The new study, published in print today in the journal Nano Letters, demonstrates how stable 'lipid membranes' – the thin 'skin' that surrounds all biological cells – can be applied to synthetic surfaces.

Importantly, the new technique can use these lipid membranes to 'draw' – akin to using them like a biological ink – with a resolution of 6 nanometres (6 billionths ...

Antarctic sea ice reaches new record maximum

2014-10-08

VIDEO:

The Arctic and the Antarctic are regions that have a lot of ice and acts as air conditioners for the Earth system. This year, Antarctic sea ice reached a record...

Click here for more information.

Sea ice surrounding Antarctica reached a new record high extent this year, covering more of the southern oceans than it has since scientists began a long-term satellite record to map sea ice extent in the late 1970s. The upward trend in the Antarctic, however, is only about ...

Neurons in human muscles emphasize the impact of the outside world

2014-10-08

Stretch sensors in our muscles participate in reflexes that serve the subconscious control of posture and movement. According to a new study published in the Journal of Neuroscience, these sensors respond weakly to muscle stretch caused by one's voluntary action, and most strongly to stretch that is imposed by external forces. The ability to reflect causality in this manner can facilitate appropriate reflex control and accurate self-perception.

"The results of the study show that stretch receptors in our muscles indicate more than which limb is moving or how fast; these ...

Treasure trove of ancient genomes helps recalibrate the human evolutionary clock

2014-10-08

Just like adjusting a watch, the key to accurately telling evolutionary time is based upon periodically calibrating against a gold standard.

Scientists have long used DNA data to develop molecular clocks that measure the rate at which DNA changes, i.e., accumulates mutations, as a premiere tool to peer into the past evolutionary timelines for the lineage of a given species. In human evolution, for example, molecular clocks, when combined with fossil evidence, have helped trace the time of the last common ancestor of chimpanzees and humans to 5-7 million years ago, and ...

Gluing chromosomes at the right place

2014-10-08

During cell division, chromosomes acquire a characteristic X-shape with the two DNA molecules (sister chromatids) linked at a central "connection region" that contains highly compacted DNA. It was unknown if rearrangements in this typical X-shape architecture could disrupt the correct separation of chromosomes. A recent study by Raquel Oliveira, from the Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência (Portugal), in collaboration with colleagues from the University of California, Santa Cruz (USA), now shows that the dislocation of particular DNA segments perturbs proper chromosome ...

Fine-tuning of bitter taste receptors may be key to animal survival

2014-10-08

One key to animal survival is bitter taste----the better to avoid ingesting potentially harmful poisons or foods. The evolution of bitter taste has been a hot topic amongst evolutionary biologists, and with more and more DNA data available, a rich area of exploration.

Now, professor Maik Behrens, et. al. examined the genetic repertoire of bitter taste receptor genes in chickens and frogs, which represent two extremes. Chickens only have 3 bitter taste receptor genes (Tas2rs), while frogs have more than 50 (humans are somewhere in the middle). They studied the different ...

Dietary fat under fire

2014-10-08

This news release is available in French. The association between saturated fat and cardiovascular risk has become a hot topic in nutrition. Researchers at the Institute of nutrition and functional foods (INAF) of Université Laval are calling for a review of dietary recommendations on saturated fat (SFA) in relation to cardiovascular disease (CVD).

In a Comment paper, published today in the journal Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism the authors provide a number of arguments for the urgency to re-assess the association between dietary saturated fat ...

Flies with colon cancer help to unravel the genetic keys to disease in humans

2014-10-08

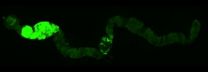

Researchers at the Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB Barcelona) have managed to generate a fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) model that reproduces human colon cancer. With two publications appearing in PLoS One and EMBO Reports, the IRB team also unveil the function of a key gene in the development of the disease.

"The breakthrough is that we have generated cancer in an adult organism and from stem cells, thus reproducing what happens in most types of human cancer. This model has allowed us to identify subtle interactions in the development of cancer that are ...

Fruit flies reveal features of human intestinal cancer

2014-10-08

HEIDELBERG, 8 October 2014 – Researchers in Spain have determined how a transcription factor known as Mirror regulates tumour-like growth in the intestines of fruit flies. The scientists believe a related system may be at work in humans during the progression of colorectal cancer due to the observation of similar genes and genetic interactions in cultured colorectal cancer cells. The results are reported in the journal EMBO Reports.

Colorectal cancer leads to more than half a million deaths worldwide each year. The disease originates in the epithelial cells of the ...