Total recall: The science behind it

RI-MUHC-led study identifies new player in brain function and memory

2014-11-13

(Press-News.org) This news release is available in French.

Montreal November 13, 2014 - Is it possible to change the amount of information the brain can store? Maybe, according to a new international study led by the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre (RI-MUHC). Their research has identified a molecule that puts a brake on brain processing and when removed, brain function and memory recall is improved. Published in the latest issue of Cell Reports, the study has implications for neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative diseases, such as autism spectral disorders and Alzheimer's disease.

"Previous research has shown that production of new molecules is necessary for storing memories in the brain; if you block the production of these molecules, new memory formation does not take place," says RI-MUHC neuroscientist, Dr. Keith Murai, the study's senior author and Associate Professor in the Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery at McGill University. "Our findings show that the brain has a key protein that limits the production of molecules necessary for memory formation. When this brake-protein is suppressed, the brain is able to store more information."

FXR1P: a controller of certain forms of memory

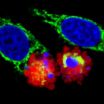

Dr. Murai and his colleagues used a mouse model to study how changes in brain cell connections produce new memories. They demonstrated that a protein, FXR1P (Fragile X Related Protein 1), was responsible for suppressing the production of molecules required for building new memories. When FXR1P was selectively removed from certain parts of the brain, these new molecules were produced that strengthened connections between brain cells and this correlated with improved memory and recall in the mice.

Disease link

"The role of FXR1P was a surprising result," says Dr. Murai who is part of the McGill Centre for Research in Neuroscience. "Previous to our work, no-one had identified a role for this regulator in the brain. Our findings have provided fundamental knowledge about how the brain processes information. We've identified a new pathway that directly regulates how information is handled and this could have relevance for understanding and treating brain diseases."

"Future research in this area could be very interesting," he adds. "If we can identify compounds that control the braking potential of FXR1P, we may be able to alter the amount of brain activity or plasticity. For example, in autism, one may want to decrease certain brain activity and in Alzheimer's disease, we may want to enhance the activity. By manipulating FXR1P, we may eventually be able to adjust memory formation and retrieval, thus improving the quality of life of people suffering from brain diseases."

INFORMATION:

About the study:

This research was made possible with funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and National Institutes of Health (U.S.A.).

Related links:

Cited Cell Reports study:

http://www.cell.com/cell-reports/abstract/S2211-1247(14)00882-1

McGill University Health Centre (MUHC): muhc.ca

Research Institute of the MUHC: rimuhc.ca

McGill University: mcgill.ca

McGill Centre for Research in Neuroscience (CRN): http://www.mcgill.ca/crn/centre-research-neuroscience

For more information please contact:

Julie Robert

Public Affairs & Strategic planning

McGill University Health Centre

514 934-1934 ext. 71381

facebook.com/cusm.muhc|http://www.muhc.ca

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2014-11-13

TORONTO, ON (13 November 2014) Astronomers from the University of Toronto and the University of Arizona have provided the first direct evidence that an intergalactic "wind" is stripping galaxies of star-forming gas as they fall into clusters of galaxies. The observations help explain why galaxies found in clusters are known to have relatively little gas and less star formation when compared to non-cluster or "field" galaxies.

Astronomers have theorized that as a field galaxy falls into a cluster of galaxies, it encounters the cloud of hot gas at the centre of the cluster. ...

2014-11-13

Some plants form into new species with a little help from their friends, according to Cornell University research published Oct. 27 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The study finds that when plants develop mutually beneficial relationships with animals, mainly insects, those plant families become more diverse by evolving into more species over time.

The researchers conducted a global analysis of all vascular plant families, more than 100 of which have evolved sugary nectar-secreting glands that attract and feed protective animals, such as ants. ...

2014-11-13

Who would have thought a Sesame Street video starring the Cookie Monster, of all characters, could teach preschoolers self-control?

But that's exactly what Deborah Linebarger, an associate professor in Teacher and Learning at the University of Iowa, found when she studied a group of preschoolers who repeatedly watched videos of Cookie Monster practicing ways to control his desire to eat a bowl of chocolate chip cookies.

"Me want it," Cookie Monster sings in one video, "but me wait."

In fact, preschoolers who viewed the Cookie Monster video were able to wait four ...

2014-11-13

In a potential breakthrough against ovarian cancer, University of Guelph researchers have discovered how to both shrink tumours and improve drug delivery, allowing for lower doses of chemotherapy and reducing side effects.

Their research appears today in the FASEB Journal, one of the world's top biology publications.

"We hope that this study will lead to novel treatment approaches for women diagnosed with late-stage ovarian cancer," said Jim Petrik, a Guelph biomedical sciences professor. He worked on the study with Guelph graduate student Samantha Russell and cancer ...

2014-11-13

LAWRENCE -- Like hedonistic rock stars that live by the "better to burn out than to fade away" credo, certain galaxies flame out in a blaze of glory. Astronomers have struggled to grasp why these young "starburst" galaxies -- ones that are very rapidly forming new stars from cold molecular hydrogen gas up to 100 times faster than our own Milky Way -- would shut down their prodigious star formation to join a category scientists call "red and dead."

Starburst galaxies typically result from the merger or close encounter of two separate galaxies. Previous research had revealed ...

2014-11-13

INDIANAPOLIS -- Researchers have identified two proteins that appear crucial to the development -- and patient relapse -- of acute myeloid leukemia. They have also shown they can block the development of leukemia by targeting those proteins.

The studies, in animal models, could lead to new effective treatments for leukemias that are resistant to chemotherapy, said Reuben Kapur, Ph.D., Freida and Albrecht Kipp Professor of Pediatrics at the Indiana University School of Medicine.

The research was reported today in the journal Cell Reports.

"The issue in the field for ...

2014-11-13

Plants all over the world are more sensitive to drought than many experts realized, according to a new study by scientists at UCLA and China's Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden. The research will improve predictions of which plant species will survive the increasingly intense droughts associated with global climate change.

The research is reported online by Ecology Letters, the most prestigious journal in the field of ecology, and will be published in an upcoming print edition.

Predicting how plants will respond to climate change is crucial for their conservation. ...

2014-11-13

MOUNT VERNON, Wash. -- A new study by researchers at Washington State University shows that mechanical harvesting of cider apples can provide labor and cost savings without affecting fruit, juice, or cider quality.

The study, published in the journal HortTechnology in October, is one of several studies focused on cider apple production in Washington State. It was conducted in response to growing demand for hard cider apples in the state and the nation.

Quenching a thirst for cider

Hard cider consumption is trending steeply upward in the region surrounding the food-conscious ...

2014-11-13

As our society ages, a University of Montreal study suggests the health system should be focussing on comorbidity and specific types of disabilities that are associated with higher health care costs for seniors, especially cognitive disabilities. Comorbidity is defined as the presence of multiple disabilities. Michaël Boissonneault and Jacques Légaré of the university's Department of Demography came to this conclusion after assessing how individual factors are associated with variation in the public costs of healthcare by studying disabled Quebecers over ...

2014-11-13

The scientists showed that the Parkin protein functions to repair or destroy damaged nerve cells, depending on the degree to which they are damaged

People living with Parkinson's disease often have a mutated form of the Parkin gene, which may explain why damaged, dysfunctional nerve cells accumulate

Dublin, Ireland, November 13th, 2014 - Scientists at Trinity College Dublin have made an important breakthrough in our understanding of Parkin - a protein that regulates the repair and replacement of nerve cells within the brain. This breakthrough generates a new perspective ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Total recall: The science behind it

RI-MUHC-led study identifies new player in brain function and memory