(Press-News.org) BOSTON - A promising experimental immunotherapy drug works best in patients whose immune defenses initially rally to attack the cancer but then are stymied by a molecular brake that shuts down the response, according to a new study led by researchers at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and the Yale University School of Medicine.

The antibody drug, known as MPDL3280A, inhibits the brake protein, PD-L1, reviving the response by immune killer T cells, which target and destroy the cancer cells. In recent clinical trials, the PD-L1 checkpoint blocker caused impressive shrinkage of kidney, melanoma, and lung tumors. But, as with other immunotherapy drugs, many patients saw no benefit.

Researchers report in the November 27 edition of Nature that the antibody was most effective when the patients' immune cells surrounding tumors expressed PD-L1 - a sign that a pre-existing immune response had been shut down by PD-L1. There was less tumor shrinkage in patients who never developed an immune response to the cancer - and, as a result, had less PD-L1 in the cancer and surrounding tissues.

"I think this is a launching point to use these findings as a predictive biomarker," said F. Stephen Hodi, MD, of Dana-Farber, senior author of the report. Hodi directs the Center for Immuno-Oncology and the Melanoma Treatment Center at Dana-Farber. First author is Roy Herbst, MD, PhD, chief of Medical Oncology at the Yale Comprehensive Cancer Center.

The scientists studied tumor tissue samples from 175 patients treated in clinical trials with MPDL3280A for advanced non-small cell lung cancer, melanoma, kidney cancer, and other cancers. On average, 18 percent of the patients had complete or partial shrinkage of their tumors, with higher or lower rates in different cancer types. Overall, the treatment was well-tolerated, with few severe side-effects, the report said.

An antibody stain that marked the presence of PD-L1 was applied to tumor samples that had been removed from patients prior to treatment. The stain revealed PD-L1 not only in the cancer cells, but also tumor-infiltrating immune cells (ICs). These are T cells and other cells of the immune response that had invaded the tumor in an attempt to destroy them.

The study found greater responses to the antibody drug in patients whose tumor cells and ICs were high in PD-L1. The scientists also looked at PD-L1 expression in samples taken from tumors while the patients were in treatment. They found that tumors that had shrunk as cells died showed increases in PD-L1 in the cancer and infiltrating immune cells.

From these findings, the researchers concluded that for the MPDL3280A antibody to be effective, the patient must have mounted an immune response that was beaten back by PD-L1. This creates a target for the PD-L1-blocking antibody, which removes the brakes on the response and allows the immune cells to attack the tumor.

The scientists called for further studies to define predictors of the response to PD-L1 blockers. "Understanding the profile of non-responders will likely provide even more valuable information," they said, "possibly revealing the diversity of mechanisms controlling anti-tumor immunity."

Scientists analyzed tissue samples from patients who had - and had not - responded to a promising new immunotherapy drug

They found that patients did best whose cancers had expression of a protein, PD-L1, in immune cells surrounding the tumor cells, to shut down an immune system attack against the cancer

The study could help identify patients most likely to respond to the new drug, which blocks PD-L1

INFORMATION:

The study was sponsored by Genentech Inc., maker of MPDL3280A.

About Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, a principal teaching affiliate of Harvard Medical School, is world renowned for its leadership in adult and pediatric cancer treatment and research. Designated as a comprehensive cancer center by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), it is one of the largest recipients among independent hospitals of NCI and National Institutes of Health grant funding. For more information, go to http://www.dana-farber.org.

MADISON, Wis. -- It was fishermen off the coast of Peru who first recognized the anomaly, hundreds of years ago. Every so often, their usually cold, nutrient-rich water would turn warm and the fish they depended on would disappear. Then there was the ceaseless rain.

They called it "El Nino," The Boy -- or Christmas Boy -- because of its timing near the holiday each time it returned, every three to seven years.

El Nino is not a contemporary phenomenon; it's long been the Earth's dominant source of year-to-year climate fluctuation. But as the climate warms and the feedbacks ...

A new study has pulled together research into the most diverse place on earth to demonstrate how the organisms below-ground could hold the key to understanding how the worlds ecosystems function and how they are responding to climate change.

Published in Nature, the paper by Professor Richard Bardgett from The University of Manchester and Professor Wim van der Putten of the Netherlands Institute of Ecology, brings together new knowledge on this previously neglected area. The paper not only highlights the sheer diversity of life that lives below-ground, but also how rapid ...

Scientists from Queen Mary University of London have made a breakthrough in developing a new therapy for advanced bladder cancer - for which there have been no major treatment advances in the past 30 years.

Published today in Nature, the study examined an antibody (MPDL3280A) which blocks a protein (PD-L1) thought to help cancer cells evade immune detection.

In a phase one, multi-centre international clinical trial, 68 patients with advanced bladder cancer (who had failed all other standard treatments such as chemotherapy) received MPDL3280A, a cancer immunotherapy ...

In the race to find materials of ever increasing thinness, surface area and conductivity to make better performing battery electrodes, a lump of clay might have just taken the lead. Materials scientists from Drexel University's College of Engineering invented the clay, which is both highly conductive and can easily be molded into a variety of shapes and sizes. It represents a turn away from the rather complicated and costly processing--currently used to make materials for lithium-ion batteries and supercapacitors--and toward one that looks a bit like rolling out cookie ...

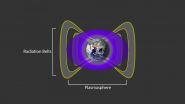

A team led by the University of Colorado Boulder has discovered an invisible shield some 7,200 miles above Earth that blocks so-called "killer electrons," which whip around the planet at near-light speed and have been known to threaten astronauts, fry satellites and degrade space systems during intense solar storms.

The barrier to the particle motion was discovered in the Van Allen radiation belts, two doughnut-shaped rings above Earth that are filled with high-energy electrons and protons, said Distinguished Professor Daniel Baker, director of CU-Boulder's Laboratory ...

In the near future, physicians may treat some cancer patients with personalized vaccines that spur their immune systems to attack malignant tumors. New research led by scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis has brought the approach one step closer to reality.

Like flu vaccines, cancer vaccines in development are designed to alert the immune system to be on the lookout for dangerous invaders. But instead of preparing the immune system for potential pathogen attacks, the vaccines will help key immune cells recognize the unique features of cancer ...

LOS ANGELES - November 26, 2014 - Work supported by the Stand Up To Cancer (SU2C) - Cancer Research Institute (CRI) - Immunology Translational Research Dream Team, launched in 2012 to focus on how the patient's own immune system can be harnessed to treat some cancers have pioneered an approach to predict why advanced melanoma patients respond to a new life-saving melanoma drug. This new drug, pembrolizumab (Keytruda), was recently approved by the FDA. These findings are reported in Nature online November 26, 2014, ahead of print in the journal.

Over a two-year study, ...

High above Earth's atmosphere, electrons whiz past at close to the speed of light. Such ultrarelativistic electrons, which make up the outer band of the Van Allen radiation belt, can streak around the planet in a mere five minutes, bombarding anything in their path. Exposure to such high-energy radiation can wreak havoc on satellite electronics, and pose serious health risks to astronauts.

Now researchers at MIT, the University of Colorado, and elsewhere have found there's a hard limit to how close ultrarelativistic electrons can get to the Earth. The team found that ...

CORVALLIS, Ore. - The use of renewable energy in the United States could take a significant leap forward with improved storage technologies or more efforts to "match" different forms of alternative energy systems that provide an overall more steady flow of electricity, researchers say in a new report.

Historically, a major drawback to the use and cost-effectiveness of alternative energy systems has been that they are too variable - if the wind doesn't blow or the sun doesn't shine, a completely different energy system has to be available to pick up the slack. This lack ...

Two donuts of seething radiation that surround Earth, called the Van Allen radiation belts, have been found to contain a nearly impenetrable barrier that prevents the fastest, most energetic electrons from reaching Earth.

The Van Allen belts are a collection of charged particles, gathered in place by Earth's magnetic field. They can wax and wane in response to incoming energy from the sun, sometimes swelling up enough to expose satellites in low-Earth orbit to damaging radiation. The discovery of the drain that acts as a barrier within the belts was made using NASA's ...