INFORMATION:

Other co-authors are Hans-Otto Portner of the Alfred Wegener Institute in Germany; Aaron Ferrel, a former graduate student at the University of California, Los Angeles; and Brad Seibel at the University of Rhode Island. The research was funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the National Science Foundation and the Alfred Wegener Institute's PACES program.

For more information, contact Deutsch at cdeutsch@uw.edu or 206-543-5189 or Huey at hueyrb@uw.edu or 206-543-1505.

Warmer, lower-oxygen oceans will shift marine habitats

2015-06-04

(Press-News.org) Modern mountain climbers typically carry tanks of oxygen to help them reach the summit. It's the combination of physical exertion and lack of oxygen at high altitudes that creates one of the biggest challenges for mountaineers.

University of Washington researchers and collaborators have found that the same principle will apply to marine species under global warming. The warmer water temperatures will speed up the animals' metabolic need for oxygen, as also happens during exercise, but the warmer water will hold less of the oxygen needed to fuel their bodies, similar to what happens at high altitudes.

The study, published June 5 in Science, finds that these changes will act together to push marine animals away from the equator. About two thirds of the respiratory stress due to climate change is caused by warmer temperatures, while the rest is because warmer water holds less dissolved gases.

"If your metabolism goes up, you need more food and you need more oxygen," said lead author Curtis Deutsch, a UW associate professor of oceanography. "This means that aquatic animals could become oxygen-starved in the warmer future, even if oxygen doesn't change. We know that oxygen levels in the ocean are going down now and will decrease more with climate warming."

The study centered on four Atlantic Ocean species whose temperature and oxygen requirements are well known from lab tests: Atlantic cod that live in the open ocean; Atlantic rock crab that live in coastal waters; sharp snout seabream that live in the subtropical Atlantic and Mediterranean; and common eelpout, a bottom-dwelling fish that lives in shallow waters in high northern latitudes.

Deutsch used climate models to see how the projected temperature and oxygen levels by 2100 due to climate change would affect these four species' ability to meet their future energy needs. If current emissions continue, the near-surface ocean is projected to warm by several degrees Celsius by the end of this century. Seawater at that temperature would hold 5-10 percent less oxygen than it does now.

Results show future rock crab habitat would be restricted to shallower water, hugging the more oxygenated surface. For all four species, the equator-ward part of the range would become uninhabitable because peak oxygen demand would become greater than the supply. Viable habitats would shift away from the equator, displacing from 14 percent to 26 percent of the current ranges.

The four animals were chosen because the effects of oxygen and temperature on their metabolism are well known, and because they live in diverse habitats. The authors believe the results are relevant for all marine species that rely on aquatic oxygen for an energy source.

"The Atlantic Ocean is relatively well oxygenated," Deutsch said. "If there's oxygen restriction in the Atlantic Ocean marine habitat, then it should be everywhere."

Climate models predict that the northern Pacific Ocean's relatively low oxygen levels will decline even further, making it the most vulnerable part of the ocean to habitat loss.

"For aquatic animals that are breathing water, warming temperatures create a real problem of limited oxygen supply versus elevated demand," said co-author Raymond Huey, a UW professor of biology who has studied metabolism in land animals and in human mountain climbers.

"This simple metabolic index seems to correlate with the current distributions of marine organisms," he said, "and that means that it gives you the power to predict how range limits are going to shift with warming."

Previously, marine scientists thought about oxygen more in terms of extreme events that could cause regional die-offs of marine animals, also known as dead zones.

"We found that oxygen is also a day-to-day restriction on where species will live, outside of those extreme events," Deutsch said. "Ranges will shift for other reasons, too, but I think the effect we're describing will be part of the mix of what's pushing species around in the future."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Few opportunities to change

2015-06-04

If you want to live, you need to breathe and muster enough energy to move, find nourishment and reproduce. This basic tenet is just as valid for us human beings as it is for the animals inhabiting our oceans. Unfortunately, most marine animals will find it harder to satisfy these criteria, which are vital to their survival, in the future. That was the key message of a new study recently published in the journal Science, in which American and German biologists defined the first universal principle on the combined effects of ocean warming and oxygen loss on the productivity ...

VirScan reveals viral history in a drop of blood

2015-06-04

From a single drop of blood, researchers can now simultaneously test for more than 1,000 different strains of viruses that currently or have previously infected a person. Using a new method known as VirScan, researchers from Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) and Harvard Medical School tested for evidence of past viral infections, detecting on average 10 viral species per person. The new work sheds light on the interplay between a person's immunity and the human virome -- the vast array of viruses that can infect humans - with implications both for the clinic and for the ...

Protein maintains double duty as key cog in body clock and metabolic control

2015-06-04

PHILADELPHIA - Around-the-clock rhythms guide nearly all physiological processes in animals and plants. Each cell in the body contains special proteins that act on one another in interlocking feedback loops to generate near-24 hour oscillations called circadian rhythms. These dictate behaviors controlled by the brain, such as sleeping and eating, as well as metabolic, hormonal, and other rhythms that are intrinsic to the organs of the body. For example, when you eat may have affects on rhythms controlling fat or sugar metabolism, illustrating how circadian and metabolic ...

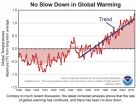

Evidence against a global warming hiatus?

2015-06-04

This news release is available in Japanese.

An analysis using updated global surface temperature data disputes the existence of a 21st century global warming slowdown described in studies including the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessment. The new analysis suggests no discernable decrease in the rate of warming between the second half of the 20th century, a period marked by manmade warming, and the first fifteen years of the 21st century, a period dubbed a global warming "hiatus." Numerous studies have been done to explain the possible ...

Habitats contracting as fish and coral flee equator

2015-06-04

This news release is available in Japanese.

Many species are migrating toward Earth's poles in response to climate change, and their habitats are shrinking in the process, researchers say. Two new reports focusing on marine organisms, which have been moving pole-ward at higher rates than terrestrial creatures, show how factors, including those not directly related to climate change, are limiting the ranges of corals and fish. Paul Muir and colleagues investigated 104 species of reef corals -- collectively known as the staghorn corals -- and confirmed the hypothesis ...

Your complete viral history revealed by VirScan

2015-06-04

This news release is available in Japanese. With less than a drop of blood, a new technology called VirScan can identify all of the viruses that individuals have been exposed to over the course of their lives. Researchers used the screening technique with 569 people from around the world and found that, on average, their participants had been exposed to about 10 viral species over their lifetimes. VirScan provides a powerful and inexpensive tool for studying interactions between the human virome -- the collection of viruses known to infect humans, some of which don't ...

News package explores emerging issues for isolated tribes

2015-06-04

This news release is available in Japanese. Some of the world's last isolated tribes are emerging from the Amazon rainforest, forcing scientists and policymakers in South America to reconsider their policies regarding contact with such people. In this special package of news, Science correspondents Andrew Lawler and Heather Pringle report from Peru and Brazil, respectively -- two countries that are dealing with a spate of first encounters. Lawler describes contact between isolated tribespeople emerging from the forest and indigenous Peruvian villagers, who themselves ...

Your viral infection history in a single drop of blood

2015-06-04

New technology developed by Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) researchers makes it possible to test for current and past infections with any known human virus by analyzing a single drop of a person's blood. The method, called VirScan, is an efficient alternative to existing diagnostics that test for specific viruses one at a time.

With VirScan, scientists can run a single test to determine which viruses have infected an individual, rather than limiting their analysis to particular viruses. That unbiased approach could uncover unexpected factors affecting individual ...

Vanishing friction

2015-06-04

Friction is all around us, working against the motion of tires on pavement, the scrawl of a pen across paper, and even the flow of proteins through the bloodstream. Whenever two surfaces come in contact, there is friction, except in very special cases where friction essentially vanishes -- a phenomenon, known as "superlubricity," in which surfaces simply slide over each other without resistance.

Now physicists at MIT have developed an experimental technique to simulate friction at the nanoscale. Using their technique, the researchers are able to directly observe individual ...

Internet privacy manifesto calls for more consumer power

2015-06-04

A revolutionary power shift from internet giants such as Google to ordinary consumers is critically overdue, according to new research from a University of East Anglia (UEA) online privacy expert.

In a manifesto that ranges from "the right to be treated fairly on the internet" to finding a better, more nuanced approach to using the internet as an archive, Dr Paul Bernal of UEA's School of Law delves deeper into his research on the so-called 'right to be forgotten.' His paper, called 'A right to be remembered? Or the internet, warts and all,' will be presented today at ...