(Press-News.org) ANN ARBOR--African-American women are equally, if not more, likely to experience infertility than their white counterparts, but they often cope with this traumatic issue in silence and isolation, according to a new University of Michigan study.

African-American women also more often feel that infertility hinders their sense of self and gender identity.

The U-M study may be among the first known to focus exclusively on African-American women and infertility. Most research has been conducted on affluent white couples seeking advanced medical interventions.

"Infertile African-American women are indeed hidden from public view," said the study's lead author, Rosario Ceballo, a U-M professor of psychology and women's studies.

Ceballo and colleagues Erin Graham and Jamie Hart interviewed 50 African-American women of different socioeconomic backgrounds about infertility and relationships with friends, relatives and doctors. Their ages ranged from 21 to 52 and most were married. Many of the women had college degrees and worked full-time.

At some point in their lives, the respondents met the medical definition for infertility, a condition in which a woman is unable to conceive after 12 or more months of regular, unprotected sex. The women spent from one to 19 years trying to become pregnant.

In describing the difficulties of getting pregnant, 32 percent of the women discussed stereotyped beliefs that equated being a woman with motherhood. Some responses included: "Emotionally, I felt that I was not complete, because I had not had a child. I didn't feel like I was a complete woman," and "It (having no biological children) would label you as a failure."

Furthermore, infertility was infused with religious significance for some women. They believed God intended women to produce children, which further heightened their sense of shame.

Virtually all of the women dealt with infertility in silence and isolation, even when a friend or relative knew about the woman's difficulty conceiving. Respondents thought infertility was not as emotionally painful for their husbands and partners, who were not interviewed for the study.

Researchers noted that some women, especially those with secondary infertility, stayed silent about being unable to conceive because discussing it did not elicit sympathy or empathy.

"Women may also reason that other people can neither change their infertility status nor understand what they were experiencing," Ceballo said.

Other reasons for women's silence about infertility may have to do with cultural expectations about strong, self-reliant black women who can cope with adversity on their own and with notions about maintaining privacy in African-American communities, she said.

In the interviews, for example, respondents said, "You don't want people in your business" and "I never said anything to anyone else because in our culture...it was not something that you shared."

With their interactions with doctors and medical professionals, about 26 percent believed that encounters may have been influenced by gender, race and/or class discrimination. These women talked about doctors who made assumptions about their sexual promiscuity and inability to pay for services or support a child.

Researchers said they were surprised to learn that highly educated women with high incomes were equally likely as low-income African-American women to report discrimination in medical settings. In addition, the cost of fertility treatments was prohibitively high for most respondents.

Overall, when black women could not conceive a child, it negatively affected their self-esteem. They saw themselves as abnormal, in part, because they did not see other people like themselves--African-American, female and infertile--in social images, Ceballo said.

The findings appear in the current issue of Psychology of Women Quarterly: myumi.ch/LR583

INFORMATION:

ATLANTA--The ability to delay gratification in chimpanzees is linked to how specific structures of the brain are connected and communicate with each other, according to researchers at Georgia State University and Kennesaw State University.

Their findings were published June 3 in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.

This study provides the first evidence in primates, including humans, of an association between delay of gratification performance and white matter connectivity between the caudate and the dorsal prefrontal cortex in the right hemisphere, ...

A tougher federal standard for ozone pollution, under consideration to improve public health, would ramp up the importance of scientific measurements and models, according to a new commentary published in the June 5 edition of Science by researchers at NOAA and its cooperative institute at the University of Colorado Boulder.

The commentary, led by Owen Cooper of the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences and NOAA's Earth System Research Laboratory, looks at how a new, stricter ozone standard would pose challenges for air quality managers at state ...

Modern mountain climbers typically carry tanks of oxygen to help them reach the summit. It's the combination of physical exertion and lack of oxygen at high altitudes that creates one of the biggest challenges for mountaineers.

University of Washington researchers and collaborators have found that the same principle will apply to marine species under global warming. The warmer water temperatures will speed up the animals' metabolic need for oxygen, as also happens during exercise, but the warmer water will hold less of the oxygen needed to fuel their bodies, similar to ...

If you want to live, you need to breathe and muster enough energy to move, find nourishment and reproduce. This basic tenet is just as valid for us human beings as it is for the animals inhabiting our oceans. Unfortunately, most marine animals will find it harder to satisfy these criteria, which are vital to their survival, in the future. That was the key message of a new study recently published in the journal Science, in which American and German biologists defined the first universal principle on the combined effects of ocean warming and oxygen loss on the productivity ...

From a single drop of blood, researchers can now simultaneously test for more than 1,000 different strains of viruses that currently or have previously infected a person. Using a new method known as VirScan, researchers from Brigham and Women's Hospital (BWH) and Harvard Medical School tested for evidence of past viral infections, detecting on average 10 viral species per person. The new work sheds light on the interplay between a person's immunity and the human virome -- the vast array of viruses that can infect humans - with implications both for the clinic and for the ...

PHILADELPHIA - Around-the-clock rhythms guide nearly all physiological processes in animals and plants. Each cell in the body contains special proteins that act on one another in interlocking feedback loops to generate near-24 hour oscillations called circadian rhythms. These dictate behaviors controlled by the brain, such as sleeping and eating, as well as metabolic, hormonal, and other rhythms that are intrinsic to the organs of the body. For example, when you eat may have affects on rhythms controlling fat or sugar metabolism, illustrating how circadian and metabolic ...

This news release is available in Japanese.

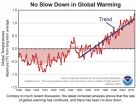

An analysis using updated global surface temperature data disputes the existence of a 21st century global warming slowdown described in studies including the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessment. The new analysis suggests no discernable decrease in the rate of warming between the second half of the 20th century, a period marked by manmade warming, and the first fifteen years of the 21st century, a period dubbed a global warming "hiatus." Numerous studies have been done to explain the possible ...

This news release is available in Japanese.

Many species are migrating toward Earth's poles in response to climate change, and their habitats are shrinking in the process, researchers say. Two new reports focusing on marine organisms, which have been moving pole-ward at higher rates than terrestrial creatures, show how factors, including those not directly related to climate change, are limiting the ranges of corals and fish. Paul Muir and colleagues investigated 104 species of reef corals -- collectively known as the staghorn corals -- and confirmed the hypothesis ...

This news release is available in Japanese. With less than a drop of blood, a new technology called VirScan can identify all of the viruses that individuals have been exposed to over the course of their lives. Researchers used the screening technique with 569 people from around the world and found that, on average, their participants had been exposed to about 10 viral species over their lifetimes. VirScan provides a powerful and inexpensive tool for studying interactions between the human virome -- the collection of viruses known to infect humans, some of which don't ...

This news release is available in Japanese. Some of the world's last isolated tribes are emerging from the Amazon rainforest, forcing scientists and policymakers in South America to reconsider their policies regarding contact with such people. In this special package of news, Science correspondents Andrew Lawler and Heather Pringle report from Peru and Brazil, respectively -- two countries that are dealing with a spate of first encounters. Lawler describes contact between isolated tribespeople emerging from the forest and indigenous Peruvian villagers, who themselves ...