That is because for decades cosmologists have had trouble reconciling the classic notion of viscosity based on the laws of thermodynamics with Einstein's general theory of relativity. However, a team from Vanderbilt University has come up with a fundamentally new mathematical formulation of the problem that appears to bridge this long-standing gap.

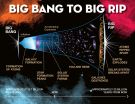

The new math has some significant implications for the ultimate fate of the universe. It tends to favor one of the more radical scenarios that cosmologists have come up with known as the "Big Rip." It may also shed new light on the basic nature of dark energy.

The new approach was developed by Assistant Professor of Mathematics Marcelo Disconzi in collaboration with physics professors Thomas Kephart and Robert Scherrer and is described in a paper published earlier this year in the journal Physical Review D.

"Marcelo has come up with a simpler and more elegant formulation that is mathematically sound and obeys all the applicable physical laws," said Scherrer.

The type of viscosity that has cosmological relevance is different from the familiar "ketchup" form of viscosity, which is called shear viscosity and is a measure of a fluid's resistance to flowing through small openings like the neck of a ketchup bottle. Instead, cosmological viscosity is a form of bulk viscosity, which is the measure of a fluid's resistance to expansion or contraction. The reason we don't often deal with bulk viscosity in everyday life is because most liquids we encounter cannot be compressed or expanded very much.

Disconzi began by tackling the problem of relativistic fluids. Astronomical objects that produce this phenomenon include supernovae (exploding stars) and neutron stars (stars that have been crushed down to the size of planets).

Scientists have had considerable success modeling what happens when ideal fluids - those with no viscosity - are boosted to near-light speeds. But almost all fluids are viscous in nature and, despite decades of effort, no one has managed to come up with a generally accepted way to handle viscous fluids traveling at relativistic velocities. In the past, the models formulated to predict what happens when these more realistic fluids are accelerated to a fraction of the speed of light have been plagued with inconsistencies: the most glaring of which has been predicting certain conditions where these fluids could travel faster than the speed of light.

"This is disastrously wrong," said Disconzi, "since it is well-proven experimentally that nothing can travel faster than the speed of light."

These problems inspired the mathematician to re-formulate the equations of relativistic fluid dynamics in a way that does not exhibit the flaw of allowing faster-than-light speeds. He based his approach on one that was advanced in the 1950s by French mathematician André Lichnerowicz.

Next, Disconzi teamed up with Kephart and Scherrer to apply his equations to broader cosmological theory. This produced a number of interesting results, including some potential new insights into the mysterious nature of dark energy.

In the 1990s, the physics community was shocked when astronomical measurements showed that the universe is expanding at an ever-accelerating rate. To explain this unpredicted acceleration, they were forced to hypothesize the existence of an unknown form of repulsive energy that is spread throughout the universe. Because they knew so little about it, they labeled it "dark energy."

Most dark energy theories to date have not taken cosmic viscosity into account, despite the fact that it has a repulsive effect strikingly similar to that of dark energy. "It is possible, but not very likely, that viscosity could account for all the acceleration that has been attributed to dark energy," said Disconzi. "It is more likely that a significant fraction of the acceleration could be due to this more prosaic cause. As a result, viscosity may act as an important constraint on the properties of dark energy."

Another interesting result involves the ultimate fate of the universe. Since the discovery of the universe's run-away expansion, cosmologists have come up with a number of dramatic scenarios of what it could mean for the future.

One scenario, dubbed the "Big Freeze," predicts that after 100 trillion years or so the universe will have grown so vast that the supplies of gas will become too thin for stars to form. As a result, existing stars will gradually burn out, leaving only black holes which, in turn, slowly evaporate away as space itself gets colder and colder.

An even more radical scenario is the "Big Rip." It is predicated on a type of "phantom" dark energy that gets stronger over time. In this case, the expansion rate of the universe becomes so great that in 22 billion years or so material objects begin to fall apart and individual atoms disassemble themselves into unbound elementary particles and radiation.

The key value involved in this scenario is the ratio between dark energy's pressure and density, what is called its equation of state parameter. If this value drops below -1 then the universe will eventually be pulled apart. Cosmologists have called this the "phantom barrier." In previous models with viscosity the universe could not evolve beyond this limit.

In the Desconzi-Kephart-Scherrer formulation, however, this barrier does not exist. Instead, it provides a natural way for the equation of state parameter to fall below -1. "In previous models with viscosity the Big Rip was not possible," said Scherrer. "In this new model, viscosity actually drives the universe toward this extreme end state."

According to the scientists, the results of their pen-and-paper analyses of this new formulation for relativistic viscosity are quite promising but a much deeper analysis must be carried out to determine its viability. The only way to do this is to use powerful computers to analyze the complex equations numerically. In this fashion the scientists can make predictions that can be compared with experiment and observation.

INFORMATION:

The research was supported by National Science Foundation grant 1305705 and Department of Energy grant DE-SC0011981.