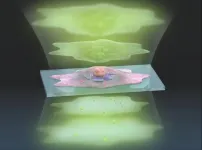

(Press-News.org) Experts in optical physics have developed a new way to see inside living cells in greater detail using existing microscopy technology and without needing to add stains or fluorescent dyes.

Since individual cells are almost translucent, microscope cameras must detect extremely subtle differences in the light passing through parts of the cell. Those differences are known as the phase of the light. Camera image sensors are limited by what amount of light phase difference they can detect, referred to as dynamic range.

"To see greater detail using the same image sensor, we must expand the dynamic range so that we can detect smaller phase changes of light," said Associate Professor Takuro Ideguchi from the University of Tokyo Institute for Photon Science and Technology.

The research team developed a technique to take two exposures to measure large and small changes in light phase separately and then seamlessly connect them to create a highly detailed final image. They named their method adaptive dynamic range shift quantitative phase imaging (ADRIFT-QPI) and recently published their results in Light: Science & Applications.

"Our ADRIFT-QPI method needs no special laser, no special microscope or image sensors; we can use live cells, we don't need any stains or fluorescence, and there is very little chance of phototoxicity," said Ideguchi.

Phototoxicity refers to killing cells with light, which can become a problem with some other imaging techniques, such as fluorescence imaging.

Quantitative phase imaging sends a pulse of a flat sheet of light towards the cell, then measures the phase shift of the light waves after they pass through the cell. Computer analysis then reconstructs an image of the major structures inside the cell. Ideguchi and his collaborators have previously pioneered other methods to enhance quantitative phase microscopy.

Quantitative phase imaging is a powerful tool for examining individual cells because it allows researchers to make detailed measurements, like tracking the growth rate of a cell based on the shift in light waves. However, the quantitative aspect of the technique has low sensitivity because of the low saturation capacity of the image sensor, so tracking nanosized particles in and around cells is not possible with a conventional approach.

The new ADRIFT-QPI method has overcome the dynamic range limitation of quantitative phase imaging. During ADRIFT-QPI, the camera takes two exposures and produces a final image that has seven times greater sensitivity than traditional quantitative phase microscopy images.

The first exposure is produced with conventional quantitative phase imaging - a flat sheet of light is pulsed towards the sample and the phase shifts of the light are measured after it passes through the sample. A computer image analysis program develops an image of the sample based on the first exposure then rapidly designs a sculpted wavefront of light that mirrors that image of the sample. A separate component called a wavefront shaping device then generates this "sculpture of light" with higher intensity light for stronger illumination and pulses it towards the sample for a second exposure.

If the first exposure produced an image that was a perfect representation of the sample, the custom-sculpted light waves of the second exposure would enter the sample at different phases, pass through the sample, then emerge as a flat sheet of light, causing the camera to see nothing but a dark image.

"This is the interesting thing: We kind of erase the sample's image. We want to see almost nothing. We cancel out the large structures so that we can see the smaller ones in great detail," Ideguchi explained.

In reality, the first exposure is imperfect, so the sculptured light waves emerge with subtle phase deviations.

The second exposure reveals tiny light phase differences that were "washed out" by larger differences in the first exposure. These remaining tiny light phase difference can be measured with increased sensitivity due to the stronger illumination used in the second exposure.

Additional computer analysis reconstructs a final image of the sample with an expanded dynamic range from the two measurement results. In proof-of-concept demonstrations, researchers estimate the ADRIFT-QPI produces images with seven times greater sensitivity than conventional quantitative phase imaging.

Ideguchi says that the true benefit of ADRIFT-QPI is its ability to see tiny particles in context of the whole living cell without needing any labels or stains.

"For example, small signals from nanoscale particles like viruses or particles moving around inside and outside a cell could be detected, which allows for simultaneous observation of their behavior and the cell's state," said Ideguchi.

INFORMATION:

Research Article

K. Toda, M. Tamamitsu, T. Ideguchi. November 2020. Adaptive dynamic range shift (ADRIFT) quantitative phase imaging. Light: Science & Applications. DOI: 10.1038/s41377-020-00435-z https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-020-00435-z

Related Links

Ideguchi Group: https://takuroideguchi.jimdo.com/

Graduate School of Science: https://www.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/index.html

Twitter: https://twitter.com/IdeguchiTakuro

Research contact

Associate Professor Takuro Ideguchi

Institute for Photon Science and Technology, The University of Tokyo Tel: +81-(0)3-5841-1026

Email: ideguchi@ipst.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp

Press officer contact

Ms. Kanako Takeda

Graduate School of Science, The University of Tokyo, 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 133-8654, JAPAN

Tel: 03-5841-0654

Email: kouhou.s@gs.mail.u-tokyo.ac.jp

About the University of Tokyo

The University of Tokyo is Japan's leading university and one of the world's top research universities. The vast research output of some 6,000 researchers is published in the world's top journals across the arts and sciences. Our vibrant student body of around 15,000 undergraduate and 15,000 graduate students includes over 4,000 international students. Find out more at http://www.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/ or follow us on Twitter at @UTokyo_News_en.

Funders

Japan Science and Technology Agency (JPMJPR17G2)

Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (17H04852, 17K19071)

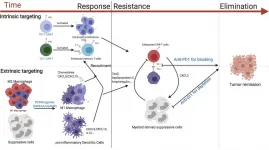

Activating an immune signaling pathway best known for fighting viral and bacterial infections can boost the ability of genetically engineered T cells to eradicate breast cancer in mice, according to a new study by researchers at the University of North Carolina. The study, to be published December 31 in the Journal of Experimental Medicine (JEM), suggests that CAR T cells, which are already used to treat certain blood cancers in humans, may also be successful against solid tumors if combined with other immunotherapeutic approaches.

Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells are a type of white blood cell that have been genetically engineered to recognize ...

The Asian tiger mosquito does not pose a major risk for Zika virus epidemics, according to a study published December 31 in the open-access journal PLOS Pathogens by Albin Fontaine of the Institut de Recherche Biomédicale des Armées, and colleagues.

Zika virus has triggered large outbreaks in human populations, in some cases causing congenital deformities, fetal loss, or neurological problems in adults. While the yellow fever mosquito Aedes aegypti is considered the primary vector of Zika ...

A novel computational drug screening strategy combined with lab experiments suggest that pralatrexate, a chemotherapy medication originally developed to treat lymphoma, could potentially be repurposed to treat Covid-19. Haiping Zhang of the Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced Technology in Shenzhen, China, and colleagues present these findings in the open-access journal PLOS Computational Biology.

With the Covid-19 pandemic causing illness and death worldwide, better treatments are urgently needed. One shortcut could be to repurpose existing drugs that were originally developed to ...

Multiple bouts of blood feeding by mosquitoes shorten the incubation period for malaria parasites and increase malaria transmission potential, according to a study published December 31 in the open-access journal PLOS Pathogens by Lauren Childs of Virginia Tech, Flaminia Catteruccia of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, and colleagues. Given that mosquitoes feed on blood multiple times in natural settings, the results suggest that malaria elimination may be substantially more challenging than suggested by previous experiments, which typically involve a single blood meal.

Malaria ...

The discovery of new drugs is vital to achieving the eradication of neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) in Africa and around the world. Now, researchers reporting in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases have identified traditional Ghanaian medicines which work in the lab against schistosomiasis, onchocerciasis and lymphatic filariasis, three diseases endemic to Ghana.

The major intervention for NTDs in Ghana is currently mass drug administration of a few repeatedly recycled drugs, which can lead to reduced efficacy and the emergence of drug resistance. Chronic infections of schistosomiasis, onchocerciasis and lymphatic filariasis ...

In the ongoing arms race between humans and the parasite that causes malaria, Taane Clark and colleagues at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) report that new mutations that enhance resistance to a drug used to prevent malaria in pregnant women and children are already common in countries fighting the disease. The new results are published December 31 in PLOS Genetics.

Malaria causes about 435,000 deaths each year, primarily in young children in sub-Saharan Africa. Despite a long-term global response, efforts to control the disease are hampered by the rise of drug-resistant strains of the parasite species that cause malaria. Sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP), ...

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- A desalination membrane acts as a filter for salty water: push the water through the membrane, get clean water suitable for agriculture, energy production and even drinking. The process seems simple enough, but it contains complex intricacies that have baffled scientists for decades -- until now.

Researchers from Penn State, The University of Texas at Austin, Iowa State University, Dow Chemical Company and DuPont Water Solutions published a key finding in understanding how membranes actually filter minerals from water, online today (Dec. 31) in Science. The article will be featured on the print edition's cover, to be issued tomorrow (Jan. ...

Predicting when and how collections of particles, robots, or animals become orderly remains a challenge across science and engineering.

In the 19th century, scientists and engineers developed the discipline of statistical mechanics, which predicts how groups of simple particles transition between order and disorder, as when a collection of randomly colliding atoms freezes to form a uniform crystal lattice.

More challenging to predict are the collective behaviors that can be achieved when the particles ...

High in the clouds, atmospheric aerosols, including anthropogenic air pollutants, increase updraft speeds in storm clouds by making the surrounding air more humid, a new study finds. The results offer a new mechanism explaining the widely observed - but poorly understood - atmospheric phenomenon and provide a physical basis for predicting increasing thunderstorm intensity, particularly in the high-aerosol regions of the tropics. Observations worldwide have highlighted aerosols' impact on weather, including their ability to strengthen convection in deep convective clouds, like those ...

A new analysis suggests that, by 2040, 19% of the world's population - accounting for 21% of the global Gross Domestic Product - will be impacted by subsidence, the sinking of the ground's surface, a phenomenon often caused by human activities such as groundwater removal, and by natural causes as well. The results, reported in a Policy Forum, represent "a key first step toward formulating effective land-subsidence policies that are lacking in most countries worldwide," the authors say. Gerardo Herrera Garcia et al. performed a large-scale ...