New technology reveals fast and slow twitch muscle fibers respond differently to exercise

2021-01-12

(Press-News.org) Exercising regularly is one of the best defences against metabolic diseases, such as obesity and diabetes - but why? It's a question that scientists are still struggling to answer. While exercising changes the molecular behaviour of muscles, it's not well understood how these molecular changes improve metabolic health.

Scientists at the University of Copenhagen have now developed a new technology that allows researchers to study muscle biology on a more detailed level - and hopefully find some new answers. They extracted 'fast' and 'slow' twitch muscle fibers from freeze-dried muscle samples that were taken before and after 12 weeks of cycling exercise training. Their comprehensive analysis of the protein expression of the fibers provides new evidence that the fiber types respond differently to exercise training.

The research, which was published in Nature Communications, also demonstrates the untapped potential of freeze-dried samples that are located in freezers around the world.

"Metabolic disorders and several muscle diseases are known to affect or spare specific fiber types, therefore detailed investigation of specific fiber types is crucial. Previous studies involving large-scale protein analysis of muscle fibers required isolation of single muscle fibers from freshly obtained muscle biopsies. Since isolation of muscle fiber is time consuming, this approach has its inherent limitations. Our method enables muscle fiber analysis of already collected muscle biopsies as well as paves the new way for future studies," says Associate Professor Atul Deshmukh from the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research (CBMR) at the University of Copenhagen.

Messy and confusing muscle samples

Skeletal muscle contains tiny fibers that can be categorised as either fast or slow twitch. Simply put, fast twitch fibers create explosive energy but get tired quickly, while slow twitch fibers are less energetic but have more endurance. Most people have an even number of both types in their muscles, but the ratio can vary widely between people. This means that exercise may benefit people differently, depending on this ratio.

In a muscle, thousands of fibers are bundled together by connective tissue and interspersed with a range of cell types with a supporting function. Because of all these different cell types, scientists can struggle to interpret the results of a whole muscle sample, and connect observed changes to specific cell types.

Understanding the potential of studying individual fibers, Atul Deshmukh teamed up with Professor Matthias Mann from the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Protein Research, and the Wojtaszewski Group from the Department of Nutrition, Exercise and Sports, both at the University of Copenhagen.

Honing in on muscle fibers

They recruited healthy individuals for 12 weeks of endurance exercise training and collected muscle samples before and after exercise, which were then freeze-dried. They then extracted fast and slow twitch muscle fibers from the samples and carried out high-resolution mass spectometry-based proteomics - a tool that allows scientists to measure thousands of proteins simultaneously in the different samples.

They identified more than 4,000 different proteins in the samples, and discovered that exercise training changed the expression of hundreds of different proteins in both fast and slow twitch fiber-types. Importantly, they discovered differences to the protein expression of the two fiber-types after exercise, which demonstrates that fast and slow twitch muscle respond differently.

"Our method can be scaled for high-throughput analysis of hundreds of individual muscle fibers from a single biopsy. Coupling this approach with the modern high sensitivity mass spectrometer may help to understand the fiber type heterogeneity in healthy and diseased skeletal muscle," says Associate Professor Atul Deshmukh from the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research (CBMR) at the University of Copenhagen.

Drugs that don't accidentally target the heart

By mass, skeletal muscle is the largest organ in the body and even small changes can have tremendous impact on whole body metabolism. Skeletal muscle is therefore an interesting pharmacological target tissue with great potential in treatment of metabolic diseases. One challenge is however to avoid side effects in heart muscle, for example, which consists of specialized fibers with some similarities to slow twitch skeletal muscle fibers.

"Thus, our fiber-type specific protein repository is a first step toward identification of skeletal muscle proteins that are specific for fast twitch fibers, allowing drug targeting and delivery to this specific fiber type and potentially avoiding side effects in the heart," says Professor Jørgen Wojtaszewski from the Department of Nutrition, Exercise and Sports at the University of Copenhagen .

INFORMATION:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-12

BOSTON -- By mid-November, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had reported that 218,439 health care workers in the U.S. had been infected with COVID-19 -- a likely underestimate due to incomplete data from states. About 3% to 4% of health care personnel who recover from coronavirus infection are expected to become "COVID long-haulers" as they cope with debilitating symptoms 12 to 18 months after the acute stage of the infection clears.

"As COVID-19 surges again, hospitals are facing a shortage of skilled frontline providers who can meet the relentless demands of caring for these patients," says Zeina N. Chemali, MD, MPH, a psychiatrist and neurologist at Massachusetts ...

2021-01-12

A group of scientists from Russia, China, and the United States predicted and then experimentally obtained barium superhydrides' new unusual superconductors. The study was published in Nature Communications.

Chemists and physicists have been hunting down room-temperature superconductors since the first half of the 20th century. Initially, high hopes were placed on metallic hydrogen, but solid metallic hydrogen can become superconducting only at extremely high pressures of several million atmospheres, as it later transpired. Chemists then tried adding other elements to hydrogen in the hope of attaining superconductivity by stabilizing the metallic state under less challenging conditions. ...

2021-01-12

Typically characterized as poisonous, corrosive and smelling of rotten eggs, hydrogen sulfide's reputation may soon get a face-lift thanks to Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers. In experiments in mice, researchers have shown the foul-smelling gas may help protect aging brain cells against Alzheimer's disease. The discovery of the biochemical reactions that make this possible opens doors to the development of new drugs to combat neurodegenerative disease.

The findings from the study are reported in the Jan. 11 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences.

"Our new data firmly link aging, neurodegeneration and cell signaling using hydrogen sulfide and other gaseous molecules within the cell," says Bindu Paul, M.Sc., Ph.D., faculty ...

2021-01-12

Climate changes prompt many important questions. Not least how it affects animals and plants: Do they adapts, gradually migrate to different areas or become extinct? And what is the role played by human activities? This applies not least to Greenland and the rest of the Artic, which are expected to see the greatest effects of climate changes.

'We know surprisingly little about marine species and ecosystems in the Arctic, as it is often costly and difficult to do fieldwork and monitor the biodiversity in this area', says Associate Professor of marine mammals and instigator of the study ...

2021-01-12

Researchers from Skoltech and their colleagues have optimized data analysis for a common method of studying the 3D structure of DNA in single cells of a Drosophila fly. The new approach allows the scientists to peek with greater confidence into individual cells to study the unique ways DNA is packaged there and get closer to understanding this crucial process's underlying mechanisms. The paper was published in the journal Nature Communications.

The reason a roughly two-meter-long strand of DNA fits into the tiny nucleus of a human cell is that chromatin, a complex of DNA and proteins, packages it ...

2021-01-12

A study of students at seven public universities across the United States has identified risk factors that may place students at higher risk for negative psychological impacts related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Factors associated with greater risk of negative impacts include the amount of time students spend on screens each day, their gender, age and other characteristics.

Research has shown many college students faced significant mental health challenges going into the COVID-19 pandemic, and experts say the pandemic has added new stressors. The findings, published in the journal PLOS ONE, could help experts tailor services ...

2021-01-12

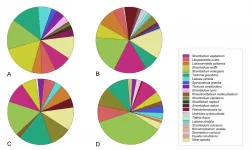

Announcing a new publication for Marine Life Science & Technology journal. In this research article the authors Hungchia Huang, Jinpeng Yang, Shixiang Huang, Bowei Gu, Ying Wang, Lei Wang and Nianzhi Jiao from Xiamen University, Xiamen, China and Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China consider the spatial distribution of planktonic ciliates in the western Pacific Ocea: along a transect from Shenzhen (China) to Pohnpei (Micronesia).

Planktonic ciliates have been recognized as major consumers of nano- and picoplankton in pelagic ecosystems, playing pivotal roles in the transfer ...

2021-01-12

COLUMBIA, Mo. - As a former school nurse in the Columbia Public Schools, Gretchen Carlisle would often interact with students with disabilities who took various medications or had seizures throughout the day. At some schools, the special education teacher would bring in dogs, guinea pigs and fish as a reward for good behavior, and Carlisle noticed what a calming presence the pets seemed to be for the students with disabilities.

Now a research scientist at the MU Research Center for Human-Animal Interaction (ReCHAI) in the MU College of Veterinary Medicine, Carlisle studies the benefits that companion animals can have on families. While there is plenty of ...

2021-01-12

New Orleans, LA - Catherine O'Neal, MD, Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine at LSU Health New Orleans School of Medicine's branch campus in Baton Rouge, is a co-author of a paper reporting that shortening the length of quarantine due to COVID exposure when supported by mid-quarantine testing may increase compliance among college athletes without increasing risk. The findings are published in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's January 8, 2021 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), available here.

CDC partnered with representatives of the NCAA conferences to analyze retrospective data collected by participating colleges and universities. De-identified data from a total of 620 ...

2021-01-12

Gut microbes passed from female mice to their offspring, or shared between mice that live together, may influence the animals' bone mass, says a new study published today in eLife.

The findings suggest that treatments which alter the gut microbiome could help improve bone structure or treat conditions that weaken bones, such as osteoporosis.

"Genetics account for most of the variability in human bone density, but non-genetic factors such as gut microbes may also play a role," says lead author Abdul Malik Tyagi, Assistant Staff Scientist at the Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism, and Lipids at Emory Microbiome Research Center, Emory University, Georgia, US. "We wanted to investigate the influence of the microbiome on skeletal growth and bone mass development."

To ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] New technology reveals fast and slow twitch muscle fibers respond differently to exercise