(Press-News.org) It's been more than a year since the first cases were identified in China, yet the exact origins of the COVID-19 pandemic remain a mystery. Though strong evidence suggests that the responsible coronavirus originated in bats, how and when it crossed from wildlife into humans is unknown.

In a study published online Jan.12 in the journal mBio, an international team of 15 biologists say this lack of clarity has exposed a glaring weakness in the current approach to pandemic surveillance and response worldwide.

In most recent studies of animal-borne pathogens with the potential to spread to humans, known as zoonotic pathogens, physical specimens of suspected wildlife hosts were not preserved. The practice of collecting and archiving specimens believed to harbor a virus, bacteria or parasite that's under investigation is called host vouchering.

"Vouchered specimens should be considered the gold standard in host-pathogen studies and a key part of pandemic preparedness," said Cody Thompson, co-lead author of the mBio paper and mammal collections manager at the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology.

"But host vouchering has effectively been nonexistent in most recent zoonotic pathogen studies, and the lack of this essential information has limited our ability to respond to the current COVID-19 pandemic," said Thompson, who is also an assistant research scientist in the U-M Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology.

To fill this knowledge gap, Thompson and his co-authors urge researchers who conduct host-pathogen studies to adopt vouchering practices and to collaborate with natural history museums to permanently archive host specimens, along with their tissue and microbiological samples.

The authors of the mBio article include experts in mammalogy, bat biology, microbiology, natural history, ornithology, bioinformatics, parasitology and host-pathogen biology. Most of them have ties to natural history museums.

"In essence, vouchering provides both an offensive mechanism for pandemic prevention--by expanding the surveillance of wildlife hosts and associated pathogens--and a defensive mechanism by providing a verifiable archive for baseline comparisons," said study co-lead author Kendra Phelps of EcoHealth Alliance, a global nonprofit that works to prevent pandemics and promote wildlife conservation.

"This problem becomes especially critical in navigating novel viral zoonoses, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, where it is necessary for the scientific community to swiftly and efficiently leverage its collective knowledge and resources to effectively understand and contain the spread of novel pathogens at a time when lockdown restrictions hamper on-going sampling efforts."

The emergence of infectious diseases attributed to novel pathogens that "spill over" from animal populations into humans has increased in recent decades.

The COVID-19 pandemic, in particular, has demonstrated that a previously unknown pathogen can emerge from wildlife species and threaten public health on a global scale within months. Experts from the World Health Organization are expected to arrive in China this week for a long-anticipated investigation into the pandemic's origins.

During spillover events, vouchered specimens in museum collections and biorepositories can help disease sleuths quickly track a pathogen to its source in the wild. The authors of the mBio study highlight three examples--yellow fever, hantaviruses and parasitic worms--of host-pathogen research that successfully incorporated natural history collections into collaborative research programs.

Vouchered host specimens can help answer fundamental biological, ecological and evolutionary questions about host-pathogen dynamics. The specimens allow for scientific replicability, they help ensure correct taxonomic identification of the host species, they establish a baseline for future studies, and they provide biological samples that can extend research as new technologies emerge.

At the same time, archiving host specimens in natural history collections provides access to a "vast, largely untapped biodiversity infrastructure" within museums, according to the authors of the mBio paper.

"We need to think of natural history collections as resources for preventing future pandemics, with the potential to promote powerful interdisciplinary and historical approaches to studying emerging zoonotic pathogens," said U-M's Thompson.

As part of their study, the mBio authors surveyed more than 100 microbiologists--bacteriologists, parasitologists and virologists--from around the world to assess their vouchering practices when conducting host-pathogen research.

Fewer than half said they voucher host specimens from which microbiological samples were lethally collected. In the cases where host specimens were obtained, most were deposited in the collections of natural history museums.

To help foster collaborations between microbiologists and curators of natural history collections, the authors also provide recommendations for integrating vouchering techniques and archiving of microbiological samples into host-pathogen studies.

INFORMATION:

In addition to Thompson and Phelps, the authors of the mBio study are:

Marc Allard of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Joseph Cook and Jonathan Dunnum of the University of New Mexico, Adam Ferguson of the Field Museum of Natural History, Magnus Gelang of the Gothenburg Natural History Museum and Gothenburg Global Biodiversity Centre in Sweden, Faisal Ali Anwarali Khan of Universiti Malaysia Sarawak in Malaysia, Deborah Paul of Florida State University (now at the University of Illinois), DeeAnn Reeder of Bucknell University, Nancy Simmons of the American Museum of Natural History, Maarten Vanhove of Hasselt University in Belgium, Paul Webala of Maasai Mara University in Kenya, Marcelo Weksler of the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro in Brazil and C. William Kilpatrick of the University of Vermont.

Funding was provided by the Consortium of European Taxonomic Facilities, Distributed System of Scientific Collections, U.S. Defense Threat Reduction Agency and U.S. National Science Foundation.

Photo: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1CMatHLe3lu8qF2qkusVa31_FMh6BFN-V

Study: Preserve a Voucher Specimen! The Critical Need for Integrating Natural History Collections in Infectious Disease Studies

Cody Thompson

Exercising regularly is one of the best defences against metabolic diseases, such as obesity and diabetes - but why? It's a question that scientists are still struggling to answer. While exercising changes the molecular behaviour of muscles, it's not well understood how these molecular changes improve metabolic health.

Scientists at the University of Copenhagen have now developed a new technology that allows researchers to study muscle biology on a more detailed level - and hopefully find some new answers. They extracted 'fast' and 'slow' twitch muscle fibers from freeze-dried muscle samples that were taken before and after 12 weeks of cycling exercise training. Their comprehensive analysis of the protein expression of the fibers provides new evidence that the ...

BOSTON -- By mid-November, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had reported that 218,439 health care workers in the U.S. had been infected with COVID-19 -- a likely underestimate due to incomplete data from states. About 3% to 4% of health care personnel who recover from coronavirus infection are expected to become "COVID long-haulers" as they cope with debilitating symptoms 12 to 18 months after the acute stage of the infection clears.

"As COVID-19 surges again, hospitals are facing a shortage of skilled frontline providers who can meet the relentless demands of caring for these patients," says Zeina N. Chemali, MD, MPH, a psychiatrist and neurologist at Massachusetts ...

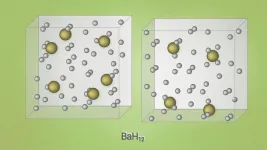

A group of scientists from Russia, China, and the United States predicted and then experimentally obtained barium superhydrides' new unusual superconductors. The study was published in Nature Communications.

Chemists and physicists have been hunting down room-temperature superconductors since the first half of the 20th century. Initially, high hopes were placed on metallic hydrogen, but solid metallic hydrogen can become superconducting only at extremely high pressures of several million atmospheres, as it later transpired. Chemists then tried adding other elements to hydrogen in the hope of attaining superconductivity by stabilizing the metallic state under less challenging conditions. ...

Typically characterized as poisonous, corrosive and smelling of rotten eggs, hydrogen sulfide's reputation may soon get a face-lift thanks to Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers. In experiments in mice, researchers have shown the foul-smelling gas may help protect aging brain cells against Alzheimer's disease. The discovery of the biochemical reactions that make this possible opens doors to the development of new drugs to combat neurodegenerative disease.

The findings from the study are reported in the Jan. 11 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences.

"Our new data firmly link aging, neurodegeneration and cell signaling using hydrogen sulfide and other gaseous molecules within the cell," says Bindu Paul, M.Sc., Ph.D., faculty ...

Climate changes prompt many important questions. Not least how it affects animals and plants: Do they adapts, gradually migrate to different areas or become extinct? And what is the role played by human activities? This applies not least to Greenland and the rest of the Artic, which are expected to see the greatest effects of climate changes.

'We know surprisingly little about marine species and ecosystems in the Arctic, as it is often costly and difficult to do fieldwork and monitor the biodiversity in this area', says Associate Professor of marine mammals and instigator of the study ...

Researchers from Skoltech and their colleagues have optimized data analysis for a common method of studying the 3D structure of DNA in single cells of a Drosophila fly. The new approach allows the scientists to peek with greater confidence into individual cells to study the unique ways DNA is packaged there and get closer to understanding this crucial process's underlying mechanisms. The paper was published in the journal Nature Communications.

The reason a roughly two-meter-long strand of DNA fits into the tiny nucleus of a human cell is that chromatin, a complex of DNA and proteins, packages it ...

A study of students at seven public universities across the United States has identified risk factors that may place students at higher risk for negative psychological impacts related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Factors associated with greater risk of negative impacts include the amount of time students spend on screens each day, their gender, age and other characteristics.

Research has shown many college students faced significant mental health challenges going into the COVID-19 pandemic, and experts say the pandemic has added new stressors. The findings, published in the journal PLOS ONE, could help experts tailor services ...

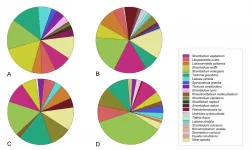

Announcing a new publication for Marine Life Science & Technology journal. In this research article the authors Hungchia Huang, Jinpeng Yang, Shixiang Huang, Bowei Gu, Ying Wang, Lei Wang and Nianzhi Jiao from Xiamen University, Xiamen, China and Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China consider the spatial distribution of planktonic ciliates in the western Pacific Ocea: along a transect from Shenzhen (China) to Pohnpei (Micronesia).

Planktonic ciliates have been recognized as major consumers of nano- and picoplankton in pelagic ecosystems, playing pivotal roles in the transfer ...

COLUMBIA, Mo. - As a former school nurse in the Columbia Public Schools, Gretchen Carlisle would often interact with students with disabilities who took various medications or had seizures throughout the day. At some schools, the special education teacher would bring in dogs, guinea pigs and fish as a reward for good behavior, and Carlisle noticed what a calming presence the pets seemed to be for the students with disabilities.

Now a research scientist at the MU Research Center for Human-Animal Interaction (ReCHAI) in the MU College of Veterinary Medicine, Carlisle studies the benefits that companion animals can have on families. While there is plenty of ...

New Orleans, LA - Catherine O'Neal, MD, Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine at LSU Health New Orleans School of Medicine's branch campus in Baton Rouge, is a co-author of a paper reporting that shortening the length of quarantine due to COVID exposure when supported by mid-quarantine testing may increase compliance among college athletes without increasing risk. The findings are published in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's January 8, 2021 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), available here.

CDC partnered with representatives of the NCAA conferences to analyze retrospective data collected by participating colleges and universities. De-identified data from a total of 620 ...