(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. - Glioblastoma brain tumors are especially perplexing. Inevitably lethal, the tumors occasionally respond to new immunotherapies after they've grown back, enabling up to 20% of patients to live well beyond predicted survival times.

What causes this effect has long been the pursuit of researchers hoping to harness immunotherapies to extend more lives.

New insights from a team led by Duke's Preston Robert Tisch Brain Tumor Center provide potential answers. The team found that recurring glioblastoma tumors with very few mutations are far more vulnerable to immunotherapies than similar tumors with an abundance of mutations.

The finding, appearing online Jan. 13 in the journal Nature Communications, could serve as a predictive biomarker to help clinicians target immunotherapies to those tumors most likely to respond. It could also potentially lead to new approaches that create the conditions necessary for immunotherapies to be more effective.

"It's been frustrating that glioblastoma is incurable and we've had limited progress improving survival despite many promising approaches," said senior author David Ashley, M.D., Ph.D., professor in the departments of Neurosurgery, Medicine, Pediatrics and Pathology at Duke University School of Medicine.

"We've had some success with several different immunotherapies, including the poliovirus therapy developed at Duke," Ashley said. "And while it's encouraging that a subset of patients who do well when the therapies are used to treat recurrent tumors, about 80% of patients still die."

Ashley and colleagues performed genomic analyses of recurrent glioblastoma tumors from patients treated at Duke with the poliovirus therapy as well as others who received so-called checkpoint inhibitors, a form of therapy that releases the immune system to attack tumors.

In both treatment groups, patients with recurrent glioblastomas whose tumors had few mutations survived longer than the patients with highly mutated tumors. This was only true, however, for patients with recurrent tumors, not for patients with newly diagnosed disease who had not yet received treatment.

"This suggests that chemotherapy, which is the standard of care for newly diagnosed glioblastoma, might be altering the inflammatory response in these tumors," Ashley said, adding that chemotherapy could be serving an important role as a primer to trigger an evolution of the inflammation process in recurrent tumors.

Ashley said the finding in glioblastoma could also be relevant to other types of tumors, including kidney and pancreatic cancers, which have similarly shown a correlation between low tumor mutations and improved response to immunotherapies.

INFORMATION:

In addition to Ashley, study authors include Matthias Gromeier, Michael C. Brown, Gao Zhang, Xiang Lin, Yeqing Chen, Zhi Wei, Nike Beaubier, Hai Yan, Yiping He, Annick Desjardins, James E. Herndon II, Frederick S. Varn, Roel G. Verhaak, Junfei Zhao, Dani P. Bolognesi, Allan H. Friedman, Henry S. Friedman, Frances McSherry, Andrea M. Muscat, Eric S. Lipp, Smita K. Nair, Mustafa Khasraw, Katherine B. Peters, Dina Randazzo, John H. Sampson, Roger E. McLendon and Darell D. Bigner.

The study received support from The Brain Tumor Research Charity, Jewish Communal Fund, Circle of Service Foundation, Uncle Kory Foundation, Department of Defense (W81XWH-16-1-0354) and the National Institutes of Health (R35CA197264, P01CA154291, P50CA190991, R01NS108773, R01NS099463, R21NS112899, P01CA225622, F32CA224593). Support was also received through the Angels Among Us fundraising event

and a gift from the Asness Family.

Authors Gromeier, Brown, Desjardins, Bolognesi, Henry Friedman, Nair, Sampson, Bigner and Ashley own intellectual property related to the poliovirus therapy, which has been licensed to Istari Oncology, Inc. Gromeier, Desjardins, Bolognesi, Allan Friedman, Henry Friedman and Bigner hold equity in Istari Oncology, Inc. Additional disclosures are provided in the published study.

Even with the COVID-19-related small dip in global carbon emissions due to limited travel and other activities, the ocean temperatures continued a trend of breaking records in 2020. A new study, authored by 20 scientists from 13 institutes around the world, reported the highest ocean temperatures since 1955 from surface level to a depth of 2,000 meters.

The report was published on January 13 in Advances in Atmospheric Sciences and concluded with a plea to the policymakers and others to consider the lasting damage warmer oceans can cause as they attempt to mitigate the ...

Today, the largest study of genetic diversity in Ukraine was published in the open science journal GigaScience. The project was an international effort, bringing together researchers in Ukraine, the US and China and is the first fruits of this collaboration to set up a new Central Europe Center for Genomic Research in Ukraine. Led by researchers at Uzhhorod National University and Oakland University in the US, the work provides genetic understanding of the historic and pre-historic migration settlements in one of the key intersections of human trade and migration between the Eurasian peoples as well as the identification of genetic variants of medical interest in the Ukrainian population that differ ...

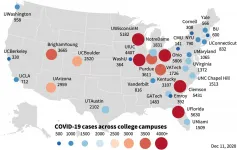

College campuses are at risk of becoming COVID-19 superspreaders for their entire county, according to a new vast study which shows the striking danger of the first two weeks of school in particular.

Looking at 30 campuses across the nation with the highest amount of reported cases, experts saw that over half of the institutions had spikes - at their peak - which were well above 1,000 coronavirus cases per 100,000 people per week within the first two weeks of class.

In some colleges, one in five students had been infected with the virus by the end of the fall term. Four institutions had over 5,000 ...

A detailed description of how ovarian cancer cells adapt to survive and proliferate in the peritoneal cavity has been published in Frontiers in Oncology. Researchers show that structures inside the cells change as the disease progresses from benign to malignant, helping the cells to grow in an otherwise hostile environment of low nutrients and oxygen. Understanding how these cellular adaptations are regulated could herald new targeted treatment options against the fifth-leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women.

"Our study compared the structures inside cells representing different stages of ovarian cancer, including after aggregation, which enhances their survival," says Eva Schmelz, a Professor and Scientific Director at Virginia Tech University, USA, who led this research. "We found ...

The remote learning experience of parents who had their children at home in Spring 2020, as schools across the US closed during the United States' COVID-19 lockdown, was more positive than widely believed.

That is the suggestion from a new study published in the Journal of School Choice, which looked at the experience of a nationally representative sample of 1,700 parents stretching right across America.

On average only 44% of parents reported the online learning program required too much of parents, while 38% of parents said it was difficult for them to manage the online provisions.

However, worryingly, most parents (63%) believed remote learning caused their child to fall behind.

While the study focused ...

Yale researchers have devised a way to peer into the brains of two people simultaneously while are engaged in discussion. What they found will not surprise anyone who has found themselves arguing about politics or social issues.

When two people agree, their brains exhibit a calm synchronicity of activity focused on sensory areas of the brain. When they disagree, however, many other regions of the brain involved in higher cognitive functions become mobilized as each individual combats the other's argument, a Yale-led research team reports Jan. 13 in the journal Frontiers of Human Neuroscience.

"Our entire brain ...

A loss of biodiversity and accelerating climate change in the coming decades coupled with ignorance and inaction is threatening the survival of all species, including our very own, according to the experts from institutions including Stanford University, UCLA, and Flinders University.

The researchers state that world leaders need a 'cold shower' regarding the state of our environment, both to plan and act to avoid a ghastly future.

Lead author Professor Corey Bradshaw of Flinders University in Australia says he and his colleagues have summarised the state of the natural world in stark form to help clarify the gravity of the human predicament.

"Humanity is causing a ...

Tsukuba, Japan - Work causes so much stress that it's become a global public health issue. Stress's impact on mental and physical health can also hurt productivity and result in economic loss. A new study now finds that working people who regularly take walks in forests or greenspaces may have higher stress-coping abilities.

In a study published in Public Health in Practice, researchers led by Professor Shinichiro Sasahara at the University of Tsukuba analyzed workers' "sense of coherence" (SOC) scores, demographic attributes, and their forest/greenspace walking habits. SOC comprises the triad of meaningfulness (finding a sense of meaning in life), comprehensibility (recognizing and understanding stress), and ...

CLEVELAND, Ohio (Jan. 13, 2021)--If you're a bit more forgetful or having more difficulty processing complex concepts than in the past, the problem may be your menopause stage. A new study claims that menopause stage is a key determinant of cognition and, contrary to previous studies, shows that certain cognitive declines may continue into the postmenopause period. Study results are published online today in Menopause, the journal of The North American Menopause Society (NAMS).

It's commonly assumed that people's memories decline with age, as does their ability to learn new things and grasp challenging concepts. ...

The ability of our skin to protect us from chemicals is something we inherit. Some people are less well-protected which could imply an increased risk of being afflicted by skin disease or cancer. A new study from Karolinska Institutet in Sweden that has been published in Environmental Health Perspectives shows how the rate of uptake of common chemicals is faster in people with a genetically weakened skin barrier.

We are continually exposed to chemicals from many different sources, for example, food, hygiene products, cosmetics and textiles. Many people are also exposed to chemicals at their place of work which can constitute a work environment problem.

The protein filaggrin is important for the structure and moisture balance of the skin, properties that affect ...