(Press-News.org) The battle to stop false news and online misinformation is not going to end any time soon, but a new finding from MIT scholars may help ease the problem.

In an experiment, the researchers discovered that fact-checking labels, when attached to online news headlines, actually work better after people read false headlines, compared to when they precede the headline or accompany it.

"We found that whether a false claim was corrected before people read it, while they read it, or after they read it influenced the effectiveness of the correction," says David Rand, an MIT professor and co-author of a new paper detailing the study's results.

Specifically, the researchers found, when "true" and "false" labels were shown immediately after participants in the experiment read headlines, it reduced people's misclassification of those headlines by 25.3 percent. By contrast, there was an 8.6 percent reduction when labels appeared along with the headlines, and a 5.7 percent decrease in misclassification when the correct label appeared beforehand.

"Timing does matter when delivering fact-checks," says Nadia M. Brashier, a cognitive neuroscientist and postdoc at Harvard University, and lead author of the paper.

The paper, "Timing Matters When Correcting Fake News," appears this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The authors are Brashier; Rand; Gordon Pennycook, an assistant professor of behavioral science at University of Regina's Hill/Levene Schools of Business; and Adam Berinsky, the Mitsui Professor of Political Science at MIT and the director of the MIT Political Experiments Research Lab.

To conduct the study, the scholars ran experiments with a total of 2,683 people, who looked at 18 true news headlines from major media sources and 18 false headlines that have been debunked by the fact-checking website snopes.com. Treatment groups of participants saw "true" and "false" tags before, during, or after reading the 36 headlines; a control group did not. All participants rated the headlines for accuracy. One week later, everyone looked at the same headlines, without any fact-check information at all, and again rated the headlines for accuracy.

The findings confounded the researchers' expectations.

"Going into the project, I had anticipated it would work best to give the correction beforehand, so that people already knew to disbelieve the false claim when they came into contact with it," Rand says. "To my surprise, we actually found the opposite. Debunking the claim after they were exposed to it was the most effective."

But why might his approach -- "debunking" rather than "prebunking," as the researchers call it -- get the best results?

The scholars write that the results are consistent with a "concurrent storage hypothesis" of cognition, which proposes that people can retain both false information and corrections in their minds at the same time. It may not be possible to get people to ignore false headlines, but people are willing to update their beliefs about them.

"Allowing people to form their own impressions of news headlines, then providing 'true' or 'false' tags afterward, might act as feedback," Brashier says. "And other research shows that feedback makes correct information 'stick.'" Importantly, this suggests that the results might be different if participants did not explicitly rate the accuracy of the headlines when being exposed to them -- for example, if they were just scrolling through their news feeds.

Overall, Berinsky suggests, the research helps inform tools that social media platforms and other content providers could use, as they look for better methods to label and limit the flow of misinformation online.

"There is no single magic bullet that can cure the problem of misinformation," says Berinsky, who has long studied political rumors and misinformation. "Studying basic questions in a systematic way is a critical step toward a portfolio of effective solutions. Like David, I was somewhat surprised by our findings, but this finding is an important step forward in helping us combat misinformation."

INFORMATION:

The study was made possible through support to the researchers provided by the National Science Foundation, the Ethics and Governance of Artificial Intelligence Initiative of the Miami Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the Reset Project of Luminate, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, and Google.

Written by Peter Dizikes, MIT News Office

A new neural network developed by researchers at the University of Eastern Finland and Kuopio University Hospital enables an easy and accurate assessment of sleep apnoea severity in patients with cerebrovascular disease. The assessment is automated and based on a simple nocturnal pulse oximetry, making it possible to easily screen for sleep apnoea in stroke units.

Up to 90% of patients experiencing a stroke have sleep apnoea, according to earlier studies conducted at Kuopio University Hospital. If left untreated, sleep apnoea can reduce the quality of life and rehabilitation of patients with stroke and increase ...

An estimated 48 million cases of foodborne illness are contracted in the United States every year, causing about 128,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). In some instances, the source is well known, such as a batch of tainted ground beef that infected 209 people with E. Coli in 2019. But 80 percent of food poisoning cases are of unknown origin, making it impossible to inform consumers of hazardous food items.

David Goldberg, assistant professor of management information systems at San Diego State University, wants to improve the traceability and ...

Overview:

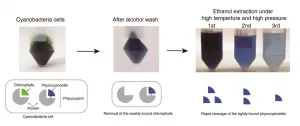

Phycocyanobilin (PCB) is a natural blue chromophore found in cyanobacteria. PCB is expected to be applied as food colorants and pharmaceuticals with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. PCB also functions as the chromophore of photoswitches that control biological functions in synthetic biology. PCB is covalently bound to phycocyanin, a component of photosynthetic antenna protein, and its extraction requires specialized expertise, time-consuming procedures, and/or expensive reagents. A research group led by Assistant Professor Yuu Hirose at Toyohashi University of Technology succeeded in developing a highly efficient and rapid extraction method for PCB by treating cyanobacterial cells with alcohol ...

The use of online messaging and social media apps among Singapore residents has spiked during the COVID-19 pandemic, a Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore) study has found.

Three in four respondents (75%) said that their use of WhatsApp during the pandemic increased. This was followed by Telegram (60.3%), Facebook (60.2%) and Instagram (59.7%).

Accompanying this spike is videoconferencing fatigue, found the NTU Singapore study, which surveyed 1,606 Singapore residents from 17 to 31 December last year. Nearly one in two Singapore residents (44%) said they felt drained from videoconferencing activities, which ...

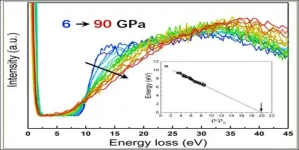

Utilizing a newly developed state-of-the-art synchrotron technique, a group of scientists led by Dr. Ho-kwang Mao, Director of HPSTAR, conducted the first-ever high-pressure study of the electronic band and gap information of solid hydrogen up to 90 GPa. Their innovative high pressure inelastic X-ray scattering result serves as a test for direct measurement of the process of hydrogen metallization and opens a possibility to resolve the electronic dispersions of dense hydrogen. This work is published in the recent issue of Physical Review Letters.

The pressure-induced evolution of hydrogen's electronic band from a wide gap insulator to a closed gap metal, or metallic ...

A group of KAIST researchers and collaborators have engineered a tiny brain implant that can be wirelessly recharged from outside the body to control brain circuits for long periods of time without battery replacement. The device is constructed of ultra-soft and bio-compliant polymers to help provide long-term compatibility with tissue. Geared with micrometer-sized LEDs (equivalent to the size of a grain of salt) mounted on ultrathin probes (the thickness of a human hair), it can wirelessly manipulate target neurons in the deep brain using light.

This study, led by Professor Jae-Woong Jeong, is a step forward from the wireless head-mounted ...

The prevalence of inflammatory bowel diseases has significantly increased both in Finland and globally. These disorders cannot be entirely cured. Instead, they are treated with anti-inflammatory drugs and, at times, through surgery.

If conventional drug therapies based on anti-inflammatory drugs are ineffective, the diseases can be treated using infliximab, a biological TNF-α blocker that is administered intravenously. Infliximab is an antibody that prevents TNF-α, a pro-inflammatory factor, from binding with inflammatory cells in the intestine. It is effective in reducing inflammation and improving the patient's condition, while also controlling the disease well.

Although infliximab therapy is often effective, roughly 30-40% of patients either do not respond ...

An international research team succeeded in gaining new insights into the artificially produced superheavy element flerovium, element 114, at the accelerator facilities of the GSI Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung in Darmstadt, Germany. Under the leadership of Lund University in Sweden and with significant participation of Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (JGU) as well as the Helmholtz Institute Mainz (HIM) in Germany and other partners, flerovium was produced and investigated to determine whether it has a closed proton shell. The results suggest that, contrary to expectations, flerovium is not a so-called "magic nucleus". The results were published in ...

Two family members test positive for COVID-19 -- how do we know who infected whom? In a perfect world, network science could provide a probable answer to such questions. It could also tell archaeologists how a shard of Greek pottery came to be found in Egypt, or help evolutionary biologists understand how a long-extinct ancestor metabolized proteins.

As the world is, scientists rarely have the historical data they need to see exactly how nodes in a network became connected. But a new paper published in Physical Review Letters offers hope for reconstructing the missing information, using a new method to evaluate the rules that generate network models.

"Network models are like impressionistic ...

A new paper from UC Santa Cruz researchers, published in END ...