(Press-News.org) In September, a team led by astronomers in the United Kingdom announced that they had detected the chemical phosphine in the thick clouds of Venus. The team's reported detection, based on observations by two Earth-based radio telescopes, surprised many Venus experts. Earth's atmosphere contains small amounts of phosphine, which may be produced by life. Phosphine on Venus generated buzz that the planet, often succinctly touted as a "hellscape," could somehow harbor life within its acidic clouds.

Since that initial claim, other science teams have cast doubt on the reliability of the phosphine detection. Now, a team led by researchers at the University of Washington has used a robust model of the conditions within the atmosphere of Venus to revisit and comprehensively reinterpret the radio telescope observations underlying the initial phosphine claim. As they report in a paper accepted to the Astrophysical Journal and posted Jan. 25 to the preprint site arXiv, the U.K.-led group likely wasn't detecting phosphine at all.

"Instead of phosphine in the clouds of Venus, the data are consistent with an alternative hypothesis: They were detecting sulfur dioxide," said co-author Victoria Meadows, a UW professor of astronomy. "Sulfur dioxide is the third-most-common chemical compound in Venus' atmosphere, and it is not considered a sign of life."

The team behind the new study also includes scientists at NASA's Caltech-based Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, the Georgia Institute of Technology, the NASA Ames Research Center and the University of California, Riverside.

The UW-led team shows that sulfur dioxide, at levels plausible for Venus, can not only explain the observations but is also more consistent with what astronomers know of the planet's atmosphere and its punishing chemical environment, which includes clouds of sulfuric acid. In addition, the researchers show that the initial signal originated not in the planet's cloud layer, but far above it, in an upper layer of Venus' atmosphere where phosphine molecules would be destroyed within seconds. This lends more support to the hypothesis that sulfur dioxide produced the signal.

Both the purported phosphine signal and this new interpretation of the data center on radio astronomy. Every chemical compound absorbs unique wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum, which includes radio waves, X-rays and visible light. Astronomers use radio waves, light and other emissions from planets to learn about their chemical composition, among other properties.

In 2017 using the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope, or JCMT, the U.K.-led team discovered a feature in the radio emissions from Venus at 266.94 gigahertz. Both phosphine and sulfur dioxide absorb radio waves near that frequency. To differentiate between the two, in 2019 the same team obtained follow-up observations of Venus using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, or ALMA. Their analysis of ALMA observations at frequencies where only sulfur dioxide absorbs led the team to conclude that sulfur dioxide levels in Venus were too low to account for the signal at 266.94 gigahertz, and that it must instead be coming from phosphine.

In this new study by the UW-led group, the researchers started by modeling conditions within Venus' atmosphere, and using that as a basis to comprehensively interpret the features that were seen -- and not seen -- in the JCMT and ALMA datasets.

"This is what's known as a radiative transfer model, and it incorporates data from several decades' worth of observations of Venus from multiple sources, including observatories here on Earth and spacecraft missions like Venus Express," said lead author Andrew Lincowski, a researcher with the UW Department of Astronomy.

The team used that model to simulate signals from phosphine and sulfur dioxide for different levels of Venus' atmosphere, and how those signals would be picked up by the JCMT and ALMA in their 2017 and 2019 configurations. Based on the shape of the 266.94-gigahertz signal picked up by the JCMT, the absorption was not coming from Venus' cloud layer, the team reports. Instead, most of the observed signal originated some 50 or more miles above the surface, in Venus' mesosphere. At that altitude, harsh chemicals and ultraviolet radiation would shred phosphine molecules within seconds.

"Phosphine in the mesosphere is even more fragile than phosphine in Venus' clouds," said Meadows. "If the JCMT signal were from phosphine in the mesosphere, then to account for the strength of the signal and the compound's sub-second lifetime at that altitude, phosphine would have to be delivered to the mesosphere at about 100 times the rate that oxygen is pumped into Earth's atmosphere by photosynthesis."

The researchers also discovered that the ALMA data likely significantly underestimated the amount of sulfur dioxide in Venus' atmosphere, an observation that the U.K.-led team had used to assert that the bulk of the 266.94-gigahertz signal was from phosphine.

"The antenna configuration of ALMA at the time of the 2019 observations has an undesirable side effect: The signals from gases that can be found nearly everywhere in Venus' atmosphere -- like sulfur dioxide -- give off weaker signals than gases distributed over a smaller scale," said co-author Alex Akins, a researcher at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

This phenomenon, known as spectral line dilution, would not have affected the JCMT observations, leading to an underestimate of how much sulfur dioxide was being seen by JCMT.

"They inferred a low detection of sulfur dioxide because of that artificially weak signal from ALMA," said Lincowski. "But our modeling suggests that the line-diluted ALMA data would have still been consistent with typical or even large amounts of Venus sulfur dioxide, which could fully explain the observed JCMT signal."

"When this new discovery was announced, the reported low sulfur dioxide abundance was at odds with what we already know about Venus and its clouds," said Meadows. "Our new work provides a complete framework that shows how typical amounts of sulfur dioxide in the Venus mesosphere can explain both the signal detections, and non-detections, in the JCMT and ALMA data, without the need for phosphine."

With science teams around the world following up with fresh observations of Earth's cloud-shrouded neighbor, this new study provides an alternative explanation to the claim that something geologically, chemically or biologically must be generating phosphine in the clouds. But though this signal appears to have a more straightforward explanation -- with a toxic atmosphere, bone-crushing pressure and some of our solar system's hottest temperatures outside of the sun -- Venus remains a world of mysteries, with much left for us to explore.

INFORMATION:

Additional co-authors are David Crisp at the JPL, Edward Schwieterman at UC Riverside, Giada Arney and Shawn Domagal-Goldman at the Goddard Space Flight Center, UW researcher Michael Wong, Paul Steffes at Georgia Tech and Niki Parenteau at NASA Ames. The research was funded by the NASA Astrobiology Program and performed at the NExSS Virtual Planetary Laboratory.

For more information, contact Meadows at meadows@uw.edu, Akins at alexander.akins@jpl.nasa.gov and Lincowski at alinc@uw.edu.

Grant number: 80NSSC18K0829

Car accidents are responsible for approximately a million deaths each year globally. Among the many causes, driving at night, when vision is most limited, leads to accidents with higher mortality rates than accidents during the day. Therefore, improving visibility during night driving is critical for reducing the number of fatal car accidents.

An adaptive driving beam (ADB) can help to some extent. This advanced drive-assist technology for vehicle headlights can automatically adjust the driver's visibility based on the car speed and traffic environment. ADB systems that ...

A combination of observational data and sophisticated computer simulations have yielded advances in a field of astrophysics that has languished for half a century. The Dark Energy Survey, which is hosted by the U.S. Department of Energy's Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory, has published a burst of new results on what's called intracluster light, or ICL, a faint type of light found inside galaxy clusters.

The first burst of new, precision ICL measurements appeared in a paper published in The Astrophysical Journal in April 2019. Another appeared more recently in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. In a surprise finding of the latter, DES physicists discovered new evidence that ICL might provide a new way to measure a mysterious substance called ...

As surgeons balance the need to control their patients' post-surgery pain with the risk that a routine operation could become the gateway to long-term opioid use or addiction, a new study shows the power of an approach that takes a middle way.

In a new letter in JAMA Surgery, a team from Michigan Medicine at the University of Michigan reports on findings from a study of 620 patients who had surgery in hospitals across Michigan, had their painkiller use tracked, and took surveys within one to three months after their operations.

Half of the patients received pre-surgery counseling that emphasized non-opioid pain treatment as their first option. Some patients in this group received small, "just in case" prescriptions, but a third of them didn't receive any opioid prescription ...

LA JOLLA--A new study led by scientists at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) suggests that T cells try to fight SARS-CoV-2 by targeting a broad range of sites on the virus--beyond the key sites on the virus's spike protein. By attacking the virus from many angles, the body has the tools to potentially recognize different SARS-CoV-2 variants.

The new research, published January 27, 2021 in Cell Report Medicine, is the most detailed analysis so far of which proteins on SARS-CoV-2 stimulate the strongest responses from the immune system's "helper" CD4+ T cells and "killer" CD8+ T cells.

"We ...

INDIANAPOLIS--Researchers at the Indiana University Melvin and Bren Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center have identified how breast cancer cells hide from immune cells to stay alive. The discovery could lead to better immunotherapy treatment for patients.

Xinna Zhang, PhD, and colleagues found that when breast cancer cells have an increased level of a protein called MAL2 on the cell surface, the cancer cells can evade immune attacks and continue to grow. The findings are published this month in The Journal of Clinical Investigation and featured on the journal's cover.

The lead author of the study, Zhang is a member of the ...

Members of Syracuse University's College of Arts and Sciences are shining new light on an enduring mystery--one that is millions of years in the making.

A team of paleontologists led by Professor Cathryn Newton has increased scientists' understanding of whether Devonian marine faunas, whose fossils are lodged in a unit of bedrock in Central New York known as the Hamilton Group, were stable for millions of years before succumbing to waves of extinctions.

Drawing on 15 years of quantitative analysis with fellow professor Jim Brower (who died in 2018), Newton has continued to probe the structure of these ancient fossil communities, among the most renowned on Earth.

The group's findings, reported by the Geological Society of America (GSA), provide critical ...

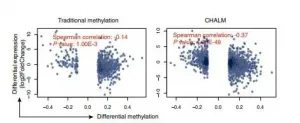

Irvine, CA - January 27, 2021 - A new University of California, Irvine-led study finds a new method for identifying biomarkers may aid in early cancer diagnosis. The study focused on lung cancer, however the Cell Heterogeneity-Adjusted cLonal Methylation (CHALM) method has been tested on aging and Alzheimer's diseases as well and is expected to be effective for studying other diseases.

"We found the CHALM method may be a valuable tool in helping researchers to identify more reliable differentially methylated genes from sequence-based methylation data," ...

Doctors are increasingly using genetic signatures to diagnose diseases and determine the best course of care, but using DNA sequencing and other techniques to detect genomic rearrangements remains costly or limited in capabilities. However, an innovative breakthrough developed by researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University Massey Cancer Center and the VCU Department of Physics promises to diagnose DNA rearrangement mutations at a fraction of the cost with improved accuracy.

Led by VCU physicist Jason Reed, Ph.D., the team developed a technique that combines a process called digital polymerase chain reaction (dPCR) with high-speed atomic force microscopy (HSAFM) to create an image with such nanoscale resolution that users can measure differences in ...

Historically redlined neighborhoods are more likely to have a paucity of greenspace today compared to other neighborhoods. The study by researchers at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and the University of California, Berkeley and San Francisco, demonstrates the lasting effects of redlining, a racist mortgage appraisal practice of the 1930s that established and exacerbated racial residential segregation in the United States. Results appear in Environmental Health Perspectives.

In the 1930s, the Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC) assigned risk grades to neighborhoods across the country based on racial demographics and other factors. "Hazardous" areas--often those whose residents included people ...

LAWRENCE -- For at least a century, ecologists have wondered at the tendency for populations of different species to cycle up and down in steady, rhythmic patterns.

"These cycles can be really exaggerated -- really huge booms and huge busts -- and quite regular," said Daniel Reuman, professor of ecology & evolutionary biology at the University of Kansas and senior scientist at the Kansas Biological Survey. "It attracted people's attention because it was kind of mysterious. Why would such a big thing be happening?"

A second observation in animal populations ...