(Press-News.org) PITTSBURGH, Feb. 4, 2021 - Researchers at UPMC Hillman Cancer Center and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) demonstrate that changing the gut microbiome can transform patients with advanced melanoma who never responded to immunotherapy--which has a failure rate of 40% for this type of cancer--into patients who do.

The results of this proof-of-principle phase II clinical trial were published online today in Science. In this study, a team of researchers from UPMC Hillman administered fecal microbiota transplants (FMT) and anti-PD-1 immunotherapy to melanoma patients who had failed all available therapies, including anti-PD-1, and then tracked clinical and immunological outcomes. Collaborators at NCI analyzed microbiome samples from these patients to understand why FMT seems to boost their response to immunotherapy.

"FMT is just a means to an end," said study co-lead author Diwakar Davar, M.D., a medical oncologist and member of the Cancer Immunology and Immunotherapy Program (CIIP) at UPMC Hillman and assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. "We know the composition of the intestinal microbiome--gut bacteria--can change the likelihood of responding to immunotherapy. But what are 'good' bacteria? There are about 100 trillion gut bacteria, and 200 times more bacterial genes in an individual's microbiome than in all of their cells put together."

Fecal transplant offers a way to capture a wide array of candidate microbes, testing trillions at once, to see whether having the "good" bacteria on board could make more people sensitive to PD-1 inhibitors. This study is among the first to test that idea in humans.

Davar and colleagues collected fecal samples from patients who responded extraordinarily well to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy and tested for infectious pathogens before giving the samples, through colonoscopy, to advanced melanoma patients who had never previously responded to immunotherapy. The patients were then given the anti-PD-1 drug pembrolizumab. And it worked.

Out of 15 advanced melanoma patients who received the combined FMT and anti-PD-1 treatment, six showed either tumor reduction or disease stabilization lasting more than a year.

"The likelihood that the patients treated in this trial would spontaneously respond to a second administration of anti-PD-1 immunotherapy is very low," said study co-senior author Hassane Zarour, M.D., a cancer immunologist and co-leader of the CIIP at UPMC Hillman as well as a professor of medicine at Pitt. "So, any positive response should be attributable to the administration of fecal transplant."

Analysis of samples taken from FMT recipients in this study revealed immunologic changes in the blood and at tumor sites suggesting increased immune cell activation in responders as well as increased immunosuppression in non-responders. Artificial intelligence linked these changes to the gut microbiome, likely caused by FMT.

Davar and Zarour hope to run a larger trial with melanoma patients, as well as evaluating whether FMT may be effective in treating other cancers. Ultimately, their goal is to replace FMT with pills containing a cocktail of the most beneficial microbes for boosting immunotherapy--but that's still several years away.

"Even if much work remains to be done, our study raises hope for microbiome-based therapies of cancers," said Zarour, who holds the James W. and Frances G. McGlothlin Chair in Melanoma Immunotherapy Research at UPMC Hillman.

INFORMATION:

Additional authors on the study include Amiran Dzutsev, M.D., John McCulloch, Ph.D., Richard Rodriguez, M.B.A., Jonathan Badger, Ph.D., Marie Vetizou, Ph.D., Alicia Cole, Miriam Fernandes, Ph.D., Stephanie Prescott, M.S.N., C.R.N.P., Rachel Costa, M.S., Ascharya Balaji and Giorgio Trinchieri, M.D., of the National Cancer Institute; Joe-Marc Chauvin, Ph.D., Robert Morrison, M.D., Richelle Deblasio, Carmine Menna, Quanquan Ding, Ph.D., Ornella Pagliano, Bochra Zidi, Ph.D., Shuowen Zhang, Hong Wang, Ph.D., Scarlett Ernst, Amy Rose, Yana Najjar, M.D., and John Kirkwood, M.D., of UPMC Hillman Cancer Center; Andrey Morgun, M.D., Ph.D., of Oregon State University; Ivan Vujkovic-Cvijin, Ph.D., and Yasmine Belkaid, Ph.D., of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; and Amir Borhani, M.D., Marc Schwartz, M.D., and Howard Dubner, M.D., of Pitt.

Funding for this study was provided by Merck and the NCI (R01 CA222203 and P30 CA047904).

To read this release online or share it, visit http://www.upmc.com/media/news/020421-Davar-Zarour-Science [when embargo lifts].

About UPMC Hillman Cancer Center

UPMC Hillman Cancer Center is the region's only National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center and is one of the largest integrated community cancer networks in the United States. Backed by the collective strength of UPMC--which is ranked No. 15 for cancer care nationally by U.S. News & World Report - and the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, UPMC Hillman Cancer Center has nearly 80 locations throughout Pennsylvania, Ohio, New York, and Maryland, with cancer centers and partnerships internationally. The more than 2,000 physicians, researchers, and staff are leaders in molecular and cellular cancer biology, cancer immunology, cancer virology, biobehavioral cancer control, and cancer epidemiology, prevention, and therapeutics. UPMC Hillman Cancer Center is transforming cancer research, care, and prevention -- one patient at a time.

About the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

As one of the nation's leading academic centers for biomedical research, the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine integrates advanced technology with basic science across a broad range of disciplines in a continuous quest to harness the power of new knowledge and improve the human condition. Driven mainly by the School of Medicine and its affiliates, Pitt has ranked among the top 10 recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health since 1998. In rankings recently released by the National Science Foundation, Pitt ranked fifth among all American universities in total federal science and engineering research and development support.

Likewise, the School of Medicine is equally committed to advancing the quality and strength of its medical and graduate education programs, for which it is recognized as an innovative leader, and to training highly skilled, compassionate clinicians and creative scientists well-equipped to engage in world-class research. The School of Medicine is the academic partner of UPMC, which has collaborated with the University to raise the standard of medical excellence in Pittsburgh and to position health care as a driving force behind the region's economy. For more information about the School of Medicine, see http://www.medschool.pitt.edu.

http://www.upmc.com/media

Contact: Erin Hare

Mobile: 412-738-1097

E-mail: HareE@upmc.edu

Contact: Cyndy Patton

Mobile: 412-415-6085

E-mail: PattonC4@upmc.edu

Despite living in the same part of the Mojave Desert, and experiencing similar conditions, mammals and birds native to this region experienced fundamentally different exposures to climate warming over the last 100 years, a new study shows; small mammal communities there remained much more stable than birds, in the face of local climate change, it reports. The study presents an integrative approach to understanding the climate vulnerability of biodiversity in rapidly warming regions. Exposure to rising temperature extremes threatens species worldwide. It is expected to push many ever closer toward extinction. Thus, understanding ...

The soundscapes of the Anthropocene ocean are fundamentally different from those of pre-industrial times, becoming more and more a raucous cacophony as the noise from human activity has grown louder and more prevalent. In a Review, Carlos Duarte and colleagues show how the rapidly changing soundscape of modern oceans impacts marine life worldwide. According to the authors, mitigating these impacts is key to achieving a healthier ocean. From the plangent songs of cetaceans to grinding arctic sea ice, the world's oceans' natural chorus is performed by a vast ensemble of geological (geophony) and biological (biophony) sounds. However, for more than a century, ...

In February 2001, the first drafts of the human genome were published. In this Special Issue of Science, "Human Genome at 20," an Editorial, a Policy Forum, a series of NextGen Voices Letters and a Perspective explore the complicated legacy of the Human Genome Project (HGP). "Millions of people today have access to their personal genomic information, with direct-to-consumer services and integration with other 'big-data' increasingly commoditizing what was rightly celebrated as a singular achievement in February 2001," writes Science Senior Editor Brad Wible.

An Editorial by Claire Frasier, director of the Institute for Genome Sciences at the University ...

Iodine plays a bigger role than thought in rapid new particle formation (NPF) in relatively pristine regions of the atmosphere, such as along marine coasts, in the Arctic boundary layer or in the upper free troposphere, according to a new study. The authors say their measurements indicate that iodine oxoacid particle formation can compete with sulfuric acid - another vapor that can form new particles under atmospheric conditions - in pristine atmospheric regions. Tiny particles suspended high in the atmosphere - aerosols - play an essential role in Earth's climate system. Clouds require airborne particles, or cloud condensation nuclei (CCN), ...

For patients with cancers that do not respond to immunotherapy drugs, adjusting the composition of microorganisms in the intestines--known as the gut microbiome--through the use of stool, or fecal, transplants may help some of these individuals respond to the immunotherapy drugs, a new study suggests. Researchers at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Center for Cancer Research, part of the National Institutes of Health, conducted the study in collaboration with investigators from UPMC Hillman Cancer Center at the University of Pittsburgh.

In the study, some patients with advanced melanoma who initially did not respond to treatment with an immune checkpoint inhibitor, a type of immunotherapy, did respond to the drug after receiving a transplant ...

Competition among sperm cells is fierce - they all want to reach the egg cell first to fertilize it. A research team from Berlin now shows in mice that the ability of sperm to move progressively depends on the protein RAC1. Optimal amounts of active protein improve the competitiveness of individual sperm, whereas aberrant activity can cause male infertility.

It is literally a race for life when millions of sperm swim towards the egg cells to fertilize them. But does pure luck decide which sperm succeeds? As it turns out, there are differences in competitiveness between individual sperm. ...

Berkeley -- In the arid Mojave Desert, small burrowing mammals like the cactus mouse, the kangaroo rat and the white-tailed antelope squirrel are weathering the hotter, drier conditions triggered by climate change much better than their winged counterparts, finds a new study published today in Science.

Over the past century, climate change has continuously nudged the Mojave's searing summer temperatures ever higher, and the blazing heat has taken its toll on the desert's birds. Researchers have documented a collapse in the region's bird populations, likely resulting ...

Treatment for HIV has improved tremendously over the past 30 years; once a death sentence, the disease is now a manageable lifelong condition in many parts of the world. Life expectancy is about the same as that of individuals without HIV, though patients must adhere to a strict regimen of daily antiretroviral therapy, or the virus will come out of hiding and reactivate. Antiretroviral therapy prevents existing virus from replicating, but it can't eliminate the infection. Many ongoing clinical trials are investigating possible ways to clear HIV infection.

In a study published Feb. 4 in the journal Science, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have identified a potential way to eradicate ...

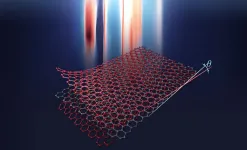

In 2018, the physics world was set ablaze with the discovery that when an ultrathin layer of carbon, called graphene, is stacked and twisted to a "magic angle," that new double layered structure converts into a superconductor, allowing electricity to flow without resistance or energy waste. Now, in a literal twist, Harvard scientists have expanded on that superconducting system by adding a third layer and rotating it, opening the door for continued advancements in graphene-based superconductivity.

The work is described in a new paper in Science and can one day help lead toward superconductors that operate at higher or even close to room temperature. These superconductors are considered the holy grail of condensed matter physics ...

Black children have significantly higher rates of shellfish and fish allergies than White children, in addition to having higher odds of wheat allergy, suggesting that race may play an important role in how children are affected by food allergies, researchers at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, Rush University Medical Center and two other hospitals have found.

Results of the study were published in the February issue of the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice.

"Food allergy is a common condition in the U.S., and we know from our previous research that there are important differences between Black and White children with food allergy, but there is so much we need to know to be able to help our patients ...