(Press-News.org) Researchers from the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) found large quantities of previously undetectable compounds from the family of chemicals known as PFAS in six watersheds on Cape Cod using a new method to quantify and identify PFAS compounds. Exposures to some PFAS, widely used for their ability to repel heat, water, and oil, are linked to a range of health risks including cancer, immune suppression, diabetes, and low infant birth weight.

The new testing method revealed large quantities of previously undetected PFAS from fire-retardant foams and other unknown sources. Total concentrations of PFAS present in these watersheds were above state maximum contaminant levels (MCLs) for drinking water safety.

"We developed a method to fully capture and characterize all PFAS from fire-retardant foams, which are a major source of PFAS to downstream drinking water and ecosystems, but we also found large amounts of unidentified PFAS that couldn't have originated from these foams," said Bridger Ruyle, a graduate student at SEAS and first author of the study. "Traditional testing methods are completely missing these unknown PFAS."

The research will be published in Environmental Science & Technology.

PFAS -- per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances -- are present in products ranging from fire retardant foams to non-stick pans. Nicknamed "forever chemicals" due to their long lifespan, PFAS have been building up in the environment since they were first used in the 1950s.

Despite the associated health risks, there are no legally enforceable federal limits for PFAS chemicals in drinking water. The Environmental Protection Agency's provisional health guidelines for public water supplies only cover PFOS and PFOA, two common types of PFAS. Massachusetts, along with a few other states, has gone further by including six PFAS in their new MCLs in drinking water. But there are thousands of PFAS chemical structures known to exist, several hundred of which have already been detected in the environment.

"We're simply not testing for most PFAS compounds, so we have no idea what our total exposure is to these chemicals and health data associated with such exposures are still lacking," said Elsie Sunderland, the Gordon McKay Professor of Environmental Chemistry at SEAS and senior author of the paper.

The standard testing methods used by the EPA and state regulatory agencies only test for 25 or fewer known compounds. The problem is the overwhelming majority of PFAS compounds are proprietary and regulatory agencies can't find what they don't know exist.

The new method developed by Sunderland and her team can overcome that barrier and account for all PFAS in a sample.

CSI: PFAS

PFAS are made by combining carbons and fluorine atoms to form one of the strongest bonds in organic chemistry. Fluorine is one of the most abundant elements on earth but naturally occurring organic fluorine is exceedingly rare -- produced only by a few poisonous plants in the Amazon and Australia. Therefore, any amount of organofluorine detected in the environment is sure to be human made.

PFAS compounds found in the environment come in two forms: a precursor form and a terminal form. Most of the monitored PFAS compounds, including PFOS and PFOA, are terminal compounds, meaning they will not degrade under normal environmental conditions. But precursor compounds, which often make up the majority of PFAS chemicals in a sample, can be transformed through biological or environmental processes into terminal forms. So, while the EPA or state agencies may monitor PFAS concentrations, they still are not detecting much of the huge pool of PFAS precursors.

That's where this new method comes in.

The researchers first measure all the organofluorine in a sample. Then, using another technique, they oxidize the precursors in that sample and transform them into their terminal forms, which they can then measure. From there, the team developed a method of statistical analysis to reconstruct the original precursors, fingerprint their manufacturing origin, and measure their concentration within the sample.

"We're essentially doing chemical forensics," said Sunderland.

Using this method, Sunderland and her team tested six watersheds on Cape Cod as part of a collaboration with the United States Geological Survey and a research center funded by the National Institutes of Health and led by the University of Rhode Island that focuses on the sources, transport, exposure and effects of PFAS.

The team focused on identifying PFAS from the use of fire-retardant foams. These foams, which are used extensively at military bases, civilian airports, and local fire departments, are a major source of PFAS and have contaminated hundreds of public water supplies across the US.

The research team applied their forensic methods to samples collected between August 2017 and July 2019 from the Childs, Quashnet, Mill Creek, Marstons Mills, Mashpee and Santuit watersheds on Cape Cod. During the collection process, the team members had to be careful what they wore, since waterproof gear is treated with PFAS. The team ended up in decades-old waders to prevent contamination.

The sampling sites in the Childs, Quashnet and Mill Creek watersheds are downstream from a source of PFAS from fire retardant foams -- the Quashnet and Childs from The Joint Base Cape Cod military facility and Mill Creek from Barnstable County Fire Training Academy.

Current tests can only identify about 50 percent of PFAS from historical foams -- products that were discontinued in 2001 due to high levels of PFOS and PFOA -- and less than 1 percent of PFAS from modern foams.

Using their new method, Sunderland and her team were able to identify 100 percent of all PFAS compounds in the types of fire-retardant foams that were used for decades at Joint Base Cape Cod and Barnstable County Fire Training Academy.

"Our testing method was able to find these missing compounds that have been used by the chemical industry for more than 40 years," said Sunderland.

The tests also revealed huge quantities of PFAS from unknown sources.

"Our accounting of PFAS from firefighting foams could not explain 37 to 77 percent of the organofluorine that we measured," said Ruyle. "This has huge ramifications for not only our understanding of human exposure but also for how much PFAS is discharging into the ocean and accumulating in marine life."

To follow up on these findings, Ruyle is currently working with NIH to identify some of the health impacts of PFAS from contemporary firefighting foams using toxicology studies. Sunderland's team is continuing to study the unknown PFAS to better identify their sources and potential for accumulation in abundant marine food webs on Cape Cod.

INFORMATION:

This paper was co-authored by Heidi Pickard, Denis LeBlanc, Andrea Tokranov, Colin Thackray, Xindi Hu and Chad Vecitis.

It was supported by the National Institute for Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) Superfund Research Program (P42ES027706) and the Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP ER18-1280). Participation by Andrea Tokranov and Denis LeBlanc was supported by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Toxic Substances Hydrology Program.

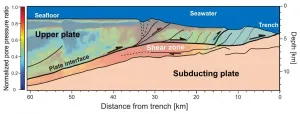

Researchers from Japan and Indonesia have pioneered a new method for more accurately estimating the source of weak ground vibrations in areas where one tectonic plate is sliding under another in the sea. Applying the approach to Japan's Nankai Trough, the researchers were able to estimate previously unknown properties in the region, demonstrating the method's promise to help probe properties needed for better monitoring and understanding larger earthquakes along this and other plate interfaces.

Episodes of small, often imperceptible seismic events ...

African American breast cancer survivors are four times more likely to die from breast cancer than women of all other races and ethnicities, and they have a disproportionately high rate of death from cardiovascular disease (CVD).

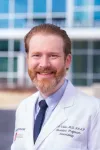

New research led by George Mason University's College of Health and Human Services faculty Dr. Michelle Williams assessed African American breast cancer survivors' risk factors and knowledge about CVD in the Deep South, where health disparities between African American women and women of other races is even larger. They found that although African American breast cancer survivors have a higher prevalence of CVD risk factors, their knowledge about CVD is low.

The study was published in the Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice in February. ...

UPTON, NY—Physicists studying collisions of gold ions at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC), a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science user facility for nuclear physics research at DOE’s Brookhaven National Laboratory, are embarking on a journey through the phases of nuclear matter—the stuff that makes up the nuclei of all the visible matter in our universe. A new analysis of collisions conducted at different energies shows tantalizing signs of a critical point—a change in the way that quarks and gluons, the building blocks of protons and neutrons, transform from one phase to another. The findings, just published by RHIC’s STAR Collaboration in the journal Physical ...

Patients can spend up to six years waiting for a kidney transplant. Even when they do receive a transplant, up to 20 percent of patients will experience rejection. Transplant rejection occurs when a recipient's immune cells recognize the newly received kidney as a foreign organ and refuse to accept the donor's antigens. Current methods for testing for kidney rejection include invasive biopsy procedures, causing patients to stay in the hospital for multiple days. A study by investigators from Brigham and Women's Hospital and Exosome Diagnostics proposes a new, noninvasive ...

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. - Studies of the microbiome in the human gut focus mainly on bacteria. Other microbes that are also present in the gut -- viruses, protists, archaea and fungi -- have been largely overlooked.

New research in mice now points to a significant role for fungi in the intestine -- the communities of molds and yeasts known as the mycobiome -- that are the active interface between the host and their diet.

"We showed that the gut mycobiome of healthy mice was shaped by the environment, including diet, and that it significantly correlated with metabolic outcomes," said Kent Willis, M.D., an assistant professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and co-corresponding author of the study, published in the journal Communications Biology. "Our results ...

JUPITER, FL -- In 1993, scientists discovered that a single mutated gene, HTT, caused Huntington's disease, raising high hopes for a quick cure. Yet today, there's still no approved treatment.

One difficulty has been a limited understanding of how the mutant huntingtin protein sets off brain cell death, says neuroscientist Srinivasa Subramaniam, PhD, of Scripps Research, Florida. In a new study published in Nature Communications on Friday, Subramaniam's group has shown that the mutated huntingtin protein slows brain cells' protein-building machines, called ribosomes.

"The ribosome has to keep moving along to build the proteins, but in Huntington's disease, the ribosome is slowed," Subramaniam says. "The difference may be two, three, four-fold ...

The body is amazing at healing itself. However, sometimes it can overdo it. Excess scarring after abdominal and pelvic surgery within the peritoneal cavity can lead to serious complications and sometimes death. The peritoneal cavity has a protective lining containing organs within our abdomen. It also contains fluid to keep the organs lubricated. When the lining gets damaged, tissue and scarring can form, creating problems. Researchers at the University of Calgary and University of Bern, Switzerland, have discovered what's causing the excess scarring and options to try to prevent it.

"This is a worldwide concern. Complications from these peritoneal adhesions cause pain and can lead to life-threatening small bowel obstruction, and infertility in women," says Dr. Joel Zindel, MD, University ...

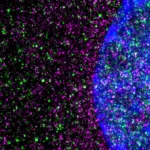

Researchers at Indiana University School of Medicine have successfully reprogrammed a glial cell type in the central nervous system into new neurons to promote recovery after spinal cord injury--revealing an untapped potential to leverage the cell for regenerative medicine.

The group of investigators published their findings March 5 in Cell Stem Cell. This is the first time scientists have reported modifying a NG2 glia--a type of supporting cell in the central nervous system--into functional neurons after spinal cord injury, said Wei Wu, PhD, research associate in neurological surgery at IU School of Medicine and co-first author of the ...

PULLMAN, Wash. - The ability to identify misinformation only benefits people who have some skepticism toward social media, according to a new study from Washington State University.

Researchers found that people with a strong trust in information found on social media sites were more likely to believe conspiracies, which falsely explain significant events as part of a secret evil plot, even if they could identify other types of misinformation. The study, published in the journal Public Understanding of Science on March 5, showed this held true for beliefs in older conspiracy theories as well as newer ones around COVID-19.

"There was some ...

Boulder, Colo., USA: In its large caldera, Newberry volcano (Oregon, USA) has two small volcanic lakes, one fed by volcanic geothermal fluids (Paulina Lake) and one by gases (East Lake). These popular fishing grounds are small windows into a large underlying reservoir of hydrothermal fluids, releasing carbon dioxide (CO2) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) with minor mercury (Hg) and methane into East Lake.

What happens to all that CO2 after it enters the bottom waters of the lake, and how do these volcanic gases influence the lake ecosystem? Some lakes fed by volcanic CO2 have seen catastrophic ...