(Press-News.org) UPTON, NY—Physicists studying collisions of gold ions at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC), a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science user facility for nuclear physics research at DOE’s Brookhaven National Laboratory, are embarking on a journey through the phases of nuclear matter—the stuff that makes up the nuclei of all the visible matter in our universe. A new analysis of collisions conducted at different energies shows tantalizing signs of a critical point—a change in the way that quarks and gluons, the building blocks of protons and neutrons, transform from one phase to another. The findings, just published by RHIC’s STAR Collaboration in the journal Physical Review Letters, will help physicists map out details of these nuclear phase changes to better understand the evolution of the universe and the conditions in the cores of neutron stars.

“If we are able to discover this critical point, then our map of nuclear phases—the nuclear phase diagram—may find a place in the textbooks, alongside that of water,” said Bedanga Mohanty of India’s National Institute of Science and Research, one of hundreds of physicists collaborating on research at RHIC using the sophisticated STAR detector.

As Mohanty noted, studying nuclear phases is somewhat like learning about the solid, liquid, and gaseous forms of water, and mapping out how the transitions take place depending on conditions like temperature and pressure. But with nuclear matter, you can’t just set a pot on the stove and watch it boil. You need powerful particle accelerators like RHIC to turn up the heat.

RHIC’s highest collision energies “melt” ordinary nuclear matter (atomic nuclei made of protons and neutrons) to create an exotic phase called a quark-gluon plasma (QGP). Scientists believe the entire universe existed as QGP a fraction of a second after the Big Bang—before it cooled and the quarks bound together (glued by gluons) to form protons, neutrons, and eventually, atomic nuclei. But the tiny drops of QGP created at RHIC measure a mere 10-13 centimeters across (that’s 0.0000000000001 cm) and they last for only 10-23 seconds! That makes it incredibly challenging to map out the melting and freezing of the matter that makes up our world.

“Strictly speaking if we don’t identify either the phase boundary or the critical point, we really can’t put this [QGP phase] into the textbooks and say that we have a new state of matter,” said Nu Xu, a STAR physicist at DOE’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Tracking phase transitions

To track the transitions, STAR physicists took advantage of the incredible versatility of RHIC to collide gold ions (the nuclei of gold atoms) across a wide range of energies.

“RHIC is the only facility that can do this, providing beams from 200 billion electron volts (GeV) all the way down to 3 GeV. Nobody can dream of such an excellent machine,” Xu said.

The changes in energy turn the collision temperature up and down and also vary a quantity known as net baryon density that is somewhat analogous to pressure. Looking at data collected during the first phase of RHIC’s “beam energy scan” from 2010 to 2017, STAR physicists tracked particles streaming out at each collision energy. They performed a detailed statistical analysis of the net number of protons produced. A number of theorists had predicted that this quantity would show large event-by-event fluctuations as the critical point is approached.

The reason for the expected fluctuations comes from a theoretical understanding of the force that governs quarks and gluons. That theory, known as quantum chromodynamics, suggests that the transition from normal nuclear matter (“hadronic” protons and neutrons) to QGP can take place in two different ways. At high temperatures, where protons and anti-protons are produced in pairs and the net baryon density is close to zero, physicists have evidence of a smooth crossover between the phases. It’s as if protons gradually melt to form QGP, like butter gradually melting on a counter on a warm day. But at lower energies, they expect what’s called a first-order phase transition—an abrupt change like water boiling at a set temperature as individual molecules escape the pot to become steam. Nuclear theorists predict that in the QGP-to-hadronic-matter phase transition, net proton production should vary dramatically as collisions approach this switchover point.

“At high energy, there is only one phase. The system is more or less invariant, normal,” Xu said. “But when we change from high energy to low energy, you also increase the net baryon density, and the structure of matter may change as you are going through the phase transition area.

“It’s just like when you ride an airplane and you get into turbulence,” he added. “You see the fluctuation—boom, boom, boom. Then, when you pass the turbulence—the phase of structural changes—you are back to normal into the one-phase structure.”

In the RHIC collision data, the signs of this turbulence are not as apparent as food and drinks bouncing off tray tables in an airplane. STAR physicists had to perform what’s known as “higher order correlation function” statistical analysis of the distributions of particles—looking for more than just the mean and width of the curve representing the data to things like how asymmetrical and skewed that distribution is.

The oscillations they see in these higher orders, particularly the skew (or kurtosis), are reminiscent of another famous phase change observed when transparent liquid carbon dioxide suddenly becomes cloudy when heated, the scientists say. This “critical opalescence” comes from dramatic fluctuations in the density of the CO2—variations in how tightly packed the molecules are.

“In our data, the oscillations signify that something interesting is happening, like the opalescence,” Mohanty said.

Yet despite the tantalizing hints, the STAR scientists acknowledge that the range of uncertainty in their measurements is still large. The team hopes to narrow that uncertainty to nail their critical point discovery by analyzing a second set of measurements made from many more collisions during phase II of RHIC’s beam energy scan, from 2019 through 2021.

The entire STAR collaboration was involved in the analysis, Xu notes, with a particular group of physicists—including Xiaofeng Luo (and his student, Yu Zhang), Ashish Pandav, and Toshihiro Nonaka, from China, India, and Japan, respectively—meeting weekly with the U.S. scientists (over many time zones and virtual networks) to discuss and refine the results. The work is also a true collaboration of the experimentalists with nuclear theorists around the world and the accelerator physicists at RHIC. The latter group, in Brookhaven Lab’s Collider-Accelerator Department, devised ways to run RHIC far below its design energy while also maximizing collision rates to enable the collection of the necessary data at low collision energies.

“We are exploring uncharted territory,” Xu said. “This has never been done before. We made lots of efforts to control the environment and make corrections, and we are eagerly awaiting the next round of higher statistical data,” he said.

INFORMATION:

This study was supported by the DOE Office of Science, the U.S. National Science Foundation, and a wide range of international funding agencies listed in the paper. RHIC operations are funded by the DOE Office of Science. Data analysis was performed using computing resources at the RHIC and ATLAS Computing Facility (RACF) at Brookhaven Lab, the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC) at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and via the Open Science Grid consortium.

Brookhaven National Laboratory is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, visit https://energy.gov/science.

Follow @BrookhavenLab on Twitter or find us on Facebook.

Related Links

Scientific paper: "Non-monotonic Energy Dependence of Net-proton Number Fluctuations"

Tracking the Transition of Early-Universe Quark Soup to Matter-as-we-know-it

How to Map the Phases of the Hottest Substance in the Universe

Tags:

nuclear physicsphysicsRHIC

2021-17357 | INT/EXT | Newsroom

Media contacts

Karen McNulty Walsh, kmcnulty@bnl.gov, 631 344-8350 [https://www.bnl.gov/staff/kmcnulty], or Peter Genzer, genzer@bnl.gov, 631 344-3174 [https://www.bnl.gov/staff/genzer]

Patients can spend up to six years waiting for a kidney transplant. Even when they do receive a transplant, up to 20 percent of patients will experience rejection. Transplant rejection occurs when a recipient's immune cells recognize the newly received kidney as a foreign organ and refuse to accept the donor's antigens. Current methods for testing for kidney rejection include invasive biopsy procedures, causing patients to stay in the hospital for multiple days. A study by investigators from Brigham and Women's Hospital and Exosome Diagnostics proposes a new, noninvasive ...

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. - Studies of the microbiome in the human gut focus mainly on bacteria. Other microbes that are also present in the gut -- viruses, protists, archaea and fungi -- have been largely overlooked.

New research in mice now points to a significant role for fungi in the intestine -- the communities of molds and yeasts known as the mycobiome -- that are the active interface between the host and their diet.

"We showed that the gut mycobiome of healthy mice was shaped by the environment, including diet, and that it significantly correlated with metabolic outcomes," said Kent Willis, M.D., an assistant professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and co-corresponding author of the study, published in the journal Communications Biology. "Our results ...

JUPITER, FL -- In 1993, scientists discovered that a single mutated gene, HTT, caused Huntington's disease, raising high hopes for a quick cure. Yet today, there's still no approved treatment.

One difficulty has been a limited understanding of how the mutant huntingtin protein sets off brain cell death, says neuroscientist Srinivasa Subramaniam, PhD, of Scripps Research, Florida. In a new study published in Nature Communications on Friday, Subramaniam's group has shown that the mutated huntingtin protein slows brain cells' protein-building machines, called ribosomes.

"The ribosome has to keep moving along to build the proteins, but in Huntington's disease, the ribosome is slowed," Subramaniam says. "The difference may be two, three, four-fold ...

The body is amazing at healing itself. However, sometimes it can overdo it. Excess scarring after abdominal and pelvic surgery within the peritoneal cavity can lead to serious complications and sometimes death. The peritoneal cavity has a protective lining containing organs within our abdomen. It also contains fluid to keep the organs lubricated. When the lining gets damaged, tissue and scarring can form, creating problems. Researchers at the University of Calgary and University of Bern, Switzerland, have discovered what's causing the excess scarring and options to try to prevent it.

"This is a worldwide concern. Complications from these peritoneal adhesions cause pain and can lead to life-threatening small bowel obstruction, and infertility in women," says Dr. Joel Zindel, MD, University ...

Researchers at Indiana University School of Medicine have successfully reprogrammed a glial cell type in the central nervous system into new neurons to promote recovery after spinal cord injury--revealing an untapped potential to leverage the cell for regenerative medicine.

The group of investigators published their findings March 5 in Cell Stem Cell. This is the first time scientists have reported modifying a NG2 glia--a type of supporting cell in the central nervous system--into functional neurons after spinal cord injury, said Wei Wu, PhD, research associate in neurological surgery at IU School of Medicine and co-first author of the ...

PULLMAN, Wash. - The ability to identify misinformation only benefits people who have some skepticism toward social media, according to a new study from Washington State University.

Researchers found that people with a strong trust in information found on social media sites were more likely to believe conspiracies, which falsely explain significant events as part of a secret evil plot, even if they could identify other types of misinformation. The study, published in the journal Public Understanding of Science on March 5, showed this held true for beliefs in older conspiracy theories as well as newer ones around COVID-19.

"There was some ...

Boulder, Colo., USA: In its large caldera, Newberry volcano (Oregon, USA) has two small volcanic lakes, one fed by volcanic geothermal fluids (Paulina Lake) and one by gases (East Lake). These popular fishing grounds are small windows into a large underlying reservoir of hydrothermal fluids, releasing carbon dioxide (CO2) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) with minor mercury (Hg) and methane into East Lake.

What happens to all that CO2 after it enters the bottom waters of the lake, and how do these volcanic gases influence the lake ecosystem? Some lakes fed by volcanic CO2 have seen catastrophic ...

Research over the last decade has shown that loneliness is an important determinant of health. It is associated with considerable physical and mental health risks and increased mortality. Previous studies have also shown that wisdom could serve as a protective factor against loneliness. This inverse relationship between loneliness and wisdom may be based in different brain processes.

In a study published in the March 5, 2021 online edition of Cerebral Cortex, researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine found that specific regions of the brain respond to emotional stimuli related to loneliness and wisdom in opposing ways.

"We were interested ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- When you think about what separates humans from chimpanzees and other apes, you might think of our big brains, or the fact that we get around on two legs rather than four. But we have another distinguishing feature: water efficiency.

That's the take-home of a new study that, for the first time, measures precisely how much water humans lose and replace each day compared with our closest living animal relatives.

Our bodies are constantly losing water: when we sweat, go to the bathroom, even when we breathe. That water needs to be replenished to keep blood volume and other body fluids within normal ranges.

And yet, research published March 5 in the journal Current Biology shows that the human body uses 30% to 50% less water per ...

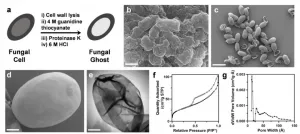

The idea of creating selectively porous materials has captured the attention of chemists for decades. Now, new research from Northwestern University shows that fungi may have been doing exactly this for millions of years.

When Nathan Gianneschi's lab set out to synthesize melanin that would mimic that which was formed by certain fungi known to inhabit unusual, hostile environments including spaceships, dishwashers and even Chernobyl, they did not initially expect the materials would prove highly porous-- a property that enables the material to store and capture molecules.

Melanin has been found across living organisms, on our skin and the backs of ...