Novel urine test developed to diagnose human kidney transplant rejection

Study demonstrates potential for a noninvasive clinical test to diagnose kidney allograft rejection and ultimately improve transplant outcomes

2021-03-05

(Press-News.org) Patients can spend up to six years waiting for a kidney transplant. Even when they do receive a transplant, up to 20 percent of patients will experience rejection. Transplant rejection occurs when a recipient's immune cells recognize the newly received kidney as a foreign organ and refuse to accept the donor's antigens. Current methods for testing for kidney rejection include invasive biopsy procedures, causing patients to stay in the hospital for multiple days. A study by investigators from Brigham and Women's Hospital and Exosome Diagnostics proposes a new, noninvasive way to test for transplant rejection using exosomes -- tiny vesicles containing mRNA -- from urine samples. Their findings are published in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

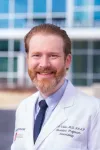

"Our goal is to develop better tools to monitor patients without performing unnecessary biopsies. We try to detect rejection early, so we can treat it before scarring develops," said Jamil Azzi, MD, associate physician in the Division of Renal Transplant at the Brigham and an associate professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School. "If rejection is not treated, it can lead to scarring and complete kidney failure. Because of these problems, recipients can face life-long challenges."

Before this study, physicians ordered biopsies or blood tests when they suspected that a transplant recipient was rejecting the donor organ. Biopsy procedures pose risks of complications, and 70-80 percent of biopsies end up being normal. Additionally, creatinine blood tests do not always yield definitive results. Because of the limitations surrounding current tests, researchers sought alternate and easier ways to assess transplant efficacy.

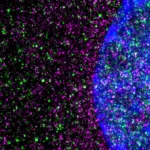

In this study, researchers took urine samples from 175 patients who were already undergoing kidney biopsies advised by physicians. From these samples, investigators isolated urinary exosomes from the immune cells of the newly transplanted kidneys. From these vesicles, researchers isolated protein and mRNA and identified a rejection signature -- a group of 15 genes -- that could distinguish between normal kidney function and rejection. Notably, researchers also identified five genes that could differentiate between two types of rejection: cellular rejection and antibody-mediated rejection.

"These findings demonstrate that exosomes isolated from urine samples may be a viable biomarker for kidney transplant rejection," said Azzi.

This research differs from prior attempts to characterize urinary mRNA because clinicians isolated exosomes rather than ordinary urine cells. The exosomal vesicle protects mRNA from degrading, allowing for the genes within the mRNA to be examined for the match rejection signature. In previous research, mRNA was isolated from cells that shed from the kidney into urine. However, without the extracellular vesicles to protect the mRNA, the mRNA decayed very quickly, making this test difficult to do in a clinical setting.

"Our paper shows that if you take urine from a patient at different points in time and measure mRNA from inside microvesicles, you get the same signature over time, allowing you to assess whether or not the transplant is being rejected," said Azzi. "Without these vesicles, you lose the genetic material after a few hours."

One limitation to this research is that these tests were done on patients undergoing a biopsy ordered by their physician, who already suspected that something was wrong. In the future, Azzi and his colleagues aim to understand whether a test such as this one can be used on kidney transplant recipients with normal kidney activity as measured in the blood to detect hidden rejection (subclinical rejection). They are currently doing a second study on patients with stable kidney function, looking to see if the same signature they identified in this current study could be used on patients without previously identified issues but still detect subclinical rejection.

"What's most exciting about this study is being able to tell patients who participated that their effort allowed us to develop something that can help more people in the future," said Azzi. "As a physician-scientist, seeing an idea that started as a frustration in the clinic, and being able to use the lab bench to develop this idea into a clinical trial, that is very fulfilling to me."

INFORMATION:

Funding for this work was provided by the American Heart Association (13FTF17000018), National Institutes of Health (RO1 AI134842), Exosome Diagnostics, NIH Clinical Center Grant (F32DK11106). Azzi reports having intellectual properties and receiving royalties from Accrue Health Inc.; receiving research funding from the American Diabetes Association, American Heart Association, and Qatar Research Fund; being a scientific advisor for CareDx; and having intellectual properties in Exosome Diagnostics. Co-authors are employees of Exosome Diagnostics, a Bio-Techne brand.

Azzi, J et al. "Discovery and Validation of a Urinary Exosome mRNA Signature for the Diagnosis of Human Kidney Transplant Rejection" Journal of the American Society of Nephrology DOI:10.1681/ASN.2020060850

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-05

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. - Studies of the microbiome in the human gut focus mainly on bacteria. Other microbes that are also present in the gut -- viruses, protists, archaea and fungi -- have been largely overlooked.

New research in mice now points to a significant role for fungi in the intestine -- the communities of molds and yeasts known as the mycobiome -- that are the active interface between the host and their diet.

"We showed that the gut mycobiome of healthy mice was shaped by the environment, including diet, and that it significantly correlated with metabolic outcomes," said Kent Willis, M.D., an assistant professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and co-corresponding author of the study, published in the journal Communications Biology. "Our results ...

2021-03-05

JUPITER, FL -- In 1993, scientists discovered that a single mutated gene, HTT, caused Huntington's disease, raising high hopes for a quick cure. Yet today, there's still no approved treatment.

One difficulty has been a limited understanding of how the mutant huntingtin protein sets off brain cell death, says neuroscientist Srinivasa Subramaniam, PhD, of Scripps Research, Florida. In a new study published in Nature Communications on Friday, Subramaniam's group has shown that the mutated huntingtin protein slows brain cells' protein-building machines, called ribosomes.

"The ribosome has to keep moving along to build the proteins, but in Huntington's disease, the ribosome is slowed," Subramaniam says. "The difference may be two, three, four-fold ...

2021-03-05

The body is amazing at healing itself. However, sometimes it can overdo it. Excess scarring after abdominal and pelvic surgery within the peritoneal cavity can lead to serious complications and sometimes death. The peritoneal cavity has a protective lining containing organs within our abdomen. It also contains fluid to keep the organs lubricated. When the lining gets damaged, tissue and scarring can form, creating problems. Researchers at the University of Calgary and University of Bern, Switzerland, have discovered what's causing the excess scarring and options to try to prevent it.

"This is a worldwide concern. Complications from these peritoneal adhesions cause pain and can lead to life-threatening small bowel obstruction, and infertility in women," says Dr. Joel Zindel, MD, University ...

2021-03-05

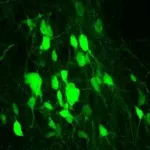

Researchers at Indiana University School of Medicine have successfully reprogrammed a glial cell type in the central nervous system into new neurons to promote recovery after spinal cord injury--revealing an untapped potential to leverage the cell for regenerative medicine.

The group of investigators published their findings March 5 in Cell Stem Cell. This is the first time scientists have reported modifying a NG2 glia--a type of supporting cell in the central nervous system--into functional neurons after spinal cord injury, said Wei Wu, PhD, research associate in neurological surgery at IU School of Medicine and co-first author of the ...

2021-03-05

PULLMAN, Wash. - The ability to identify misinformation only benefits people who have some skepticism toward social media, according to a new study from Washington State University.

Researchers found that people with a strong trust in information found on social media sites were more likely to believe conspiracies, which falsely explain significant events as part of a secret evil plot, even if they could identify other types of misinformation. The study, published in the journal Public Understanding of Science on March 5, showed this held true for beliefs in older conspiracy theories as well as newer ones around COVID-19.

"There was some ...

2021-03-05

Boulder, Colo., USA: In its large caldera, Newberry volcano (Oregon, USA) has two small volcanic lakes, one fed by volcanic geothermal fluids (Paulina Lake) and one by gases (East Lake). These popular fishing grounds are small windows into a large underlying reservoir of hydrothermal fluids, releasing carbon dioxide (CO2) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) with minor mercury (Hg) and methane into East Lake.

What happens to all that CO2 after it enters the bottom waters of the lake, and how do these volcanic gases influence the lake ecosystem? Some lakes fed by volcanic CO2 have seen catastrophic ...

2021-03-05

Research over the last decade has shown that loneliness is an important determinant of health. It is associated with considerable physical and mental health risks and increased mortality. Previous studies have also shown that wisdom could serve as a protective factor against loneliness. This inverse relationship between loneliness and wisdom may be based in different brain processes.

In a study published in the March 5, 2021 online edition of Cerebral Cortex, researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine found that specific regions of the brain respond to emotional stimuli related to loneliness and wisdom in opposing ways.

"We were interested ...

2021-03-05

DURHAM, N.C. -- When you think about what separates humans from chimpanzees and other apes, you might think of our big brains, or the fact that we get around on two legs rather than four. But we have another distinguishing feature: water efficiency.

That's the take-home of a new study that, for the first time, measures precisely how much water humans lose and replace each day compared with our closest living animal relatives.

Our bodies are constantly losing water: when we sweat, go to the bathroom, even when we breathe. That water needs to be replenished to keep blood volume and other body fluids within normal ranges.

And yet, research published March 5 in the journal Current Biology shows that the human body uses 30% to 50% less water per ...

2021-03-05

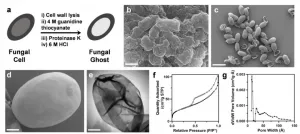

The idea of creating selectively porous materials has captured the attention of chemists for decades. Now, new research from Northwestern University shows that fungi may have been doing exactly this for millions of years.

When Nathan Gianneschi's lab set out to synthesize melanin that would mimic that which was formed by certain fungi known to inhabit unusual, hostile environments including spaceships, dishwashers and even Chernobyl, they did not initially expect the materials would prove highly porous-- a property that enables the material to store and capture molecules.

Melanin has been found across living organisms, on our skin and the backs of ...

2021-03-05

Using genetic engineering, researchers at UT Southwestern and Indiana University have reprogrammed scar-forming cells in mouse spinal cords to create new nerve cells, spurring recovery after spinal cord injury. The findings, published online today in Cell Stem Cell, could offer hope for the hundreds of thousands of people worldwide who suffer a spinal cord injury each year.

Cells in some body tissues proliferate after injury, replacing dead or damaged cells as part of healing. However, explains study leader END ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Novel urine test developed to diagnose human kidney transplant rejection

Study demonstrates potential for a noninvasive clinical test to diagnose kidney allograft rejection and ultimately improve transplant outcomes